A history of… showers

You really didn't want to have one in the 18th century, and they were still terrifying in the 19th…

Regular readers of these pieces may be forgiven for thinking that when seeking inspiration for what to write about I simply take a look around my bathroom. After all, I have written pieces about shampoo, toothbrushes, deodorant and toilet paper. I fear that I will do nothing to change that view by writing this week about showers, but trust me, they have a fascinating history!

The ancient Romans were famous for their bathing, and while this mostly consisted of steaming and soaking and scraping they did have a form of proto-shower – they would sit in a shallow bath and have water poured over them by slaves. It was important to keep an eye on your belongings when this was going on, else someone might steal your clothes. We know this from a curse tablet, a thin sheet of lead inscribed with a request to a god to take revenge upon an enemy, that was found at the site of the Roman baths in Bath, England (such tablets were usually thrown into water as it was believed that this would bring them closer to the underworld):

Solinus to the goddess Sulis Minerva. I give to your divinity and majesty my bathing tunic and cloak. Do not allow sleep or health to him who has done me wrong, whether man or woman, whether slave or free, unless he reveals himself and brings those goods to your temple.

The ancient Greeks had sufficiently advanced plumbing to have something not too dissimilar to the modern shower. Water from aqueducts would be run through pipes and out through outlets that people could stand under and get clean. This was fairly advanced stuff at the time and so tended to be found at large, public baths. These nozzles could be pretty fancy, as this illustration, made in 1937 but based upon a painting on a pot from the sixth century BCE, shows:

Bathing in general and showers in particular fell into something of a decline in Europe after the fall of the Western Roman Empire. Contrary to popular belief, bathing did exist during the medieval period, though only the rich were able to do so with a degree of comfort. Henry VIII had a second-floor bath house with hot and cold running water installed at Hampton Court Palace (charcoal burners heated a hot water cistern) which acquired its water from a spring three miles away through lead pipes that ran underneath the River Thames!

Showering didn’t really become a thing in England until the 18th century, and when it did it wasn’t for cleanliness, but rather for a much more gruesome purpose. Patrick Blair (c.1670–1728) was a Scottish surgeon of renown and a Fellow of the Royal Society. Among his many achievements were dissecting the body of an elephant that died by the side of the road just outside of Dundee and also that of a porter who hanged himself in St Andrews University.1 His role in the history of showers comes from his interest in psychiatry. At the time there was a popular view that psychological diseases were caused by the brain suffering from inflation and a ‘violent heat’ (this could be the origin of the phrase ‘hot-headed’). Such patients could be ‘cured’ by dumping a load of cold water on their heads (in a similar manner to using an ice pack to relieve the pain of a sprained and swollen joint).

Was this then an 18th-century version of the ‘ice bucket challenge’? No, sadly not, as it was also believed that inducing fear in the patient could help restore their brain to order. And so Blair decided to construct the most chilling (both literally and figuratively) shower ever devised. He took over an abandoned 35-foot-tall (11 metres) water tower and pumped 15 tonnes of ice cold water into it. His victim, sorry, patient, would then be stripped naked, strapped to a chair, blindfolded, and over the course of 30–90 minutes have the water dropped on them.

One of his patients was a woman who was clearly insane – because she wanted to leave her husband. The first time Blair tied her to the chair it:

…put her in an unexpressable terrour especially when the water was let down. I kept her under the fall 30 minutes, stopping the pipe now and then and enquiring whether she would take to her husband but she still obstinately deny’d till at last being much fatigu’d with the pressure of the water she promised she would do what I desired.

Alas she went back on her promise and so he did it to her again the following day. And then again. Finally:

I threatned her with the fourth Tryal, took her out of bed, had her stript, blindfolded and ready to be put in the Chair when she being terrify’d with what she was to undergo she kneeld submissively that I would spare her and she would become a Loving obedient and dutifull Wife for ever thereafter. I granted her request provided she would go to bed that night with her husband, which she did with great cheerfulness.

And this time it worked, as Blair reported:

About 1 month afterwards I went to pay her a visit, saw every thing in good order

This success convinced Blair that:

“Fall of water” [was]… the safest method of curing mad people... and sink the patients spirits even to a deliquium without the least hazard of their Lives.

To the modern reader this is clearly a brutal form of coercion, and yet it was the work of Blair,2 and others like him, that resulted in various forms of the same approach being used in psychiatric hospitals for the next two hundred years, such as this, reported in 1796:

…in a wing of the [Pennsylvania] hospital, particularly appropriated to the reception of insane patients, a space, about three feet square, was left in the flooring of the galleries communicating with the cells on each story. This space was occupied by a strong wooden lattice, or grating, divided into spaces of about one inch square. As these lattices were placed in an exactly perpendicular direction, one over the other, it was easy for the medical attendant to subject the patient to any degree of impression required, by directing the water to be thrown from the height of one, two, or three stories…

By the end of the century showers were become used by people who were not in the clutches of nefarious doctors, but again the purpose was therapeutic, rather than cleansing, as 1799’s Lectures on Diet and Regime3 reveal:

Although the Shower Bath does not cover the surface of the body as universally as the usual cold baths, this circumstance is rather favourable than otherwise for those parts, which the water has not touched, feel the impression by sympathy, as much as those in actual contact with it. Every drop of water becomes a partial cold bath in miniature, and thus a stronger impression is excited than in any other mode of bathing.

The heavy pressure on the body occasioned by the weight of the water, and the free circulation of the blood in the parts touched by it, being, for some time at least, interrupted, make the usual way of bathing often more detrimental than useful. The Shower Bath, on the contrary, descends in single drops, which are at once more stimulating and pleasant than the immersion into cold water, and it can be more readily procured, and more easily modified and adapted to the circumstances of the patient.

If you search online for the invention of the shower, you will find numerous references to the first patent for a shower being awarded in 1767 to one William Feetham. This isn’t true,4 as a quick search of patent records shows. Feetham patented his shower in 1822:

Feetham’s shower was a fairly elegant device, with almost bamboo-like pipes holding up a water tank which was filled by the use of a hand pump in the base of the contraption:

Interestingly Feetham still describes the user of this device as a patient in his application:

The intention of these improvements is to enable the patient, who is using the bath to regulate the flow of water, and thereby to soften the shower according as inclination or circumstances may require. This object is effected by two contrivances: the first is an adjustable stop, which may be set so as to prevent the cock from turning beyond any certain distance, so as to limit the opening of the water way to any required discharge; the second is a division of the perforated box or strainer into several chambers by two or more circular concentric partitions, by which limited quantities of water let out from the cistern above are necessarily confined to limited portions of the surface of the strainer.

And there is good reason for this. As a means of cleaning it wasn’t great, or at least not better than the alternative of having a bath. The water would have cooled very rapidly, and the dirty water continually washed over oneself. While the latter point is true of a bath as well, the volume of water in a shower was much less, so the water was dirtier. Additionally either you – or a servant – had to keep laboriously pumping the thing. As late as the 1850s we can find showers being described as therapeutic, rather than cleansing, devices as this entry in Lady Godey’s Journal from 1855 shows (and seemingly it still could be a terrifying thing!):

The shower-bath has the merit of being attainable by most persons, at any rate when at home, and is now made in various portable shapes. The shock communicated by it is not always safe; but it is powerful in its action, and the first disagreeable sensation after pulling the fatal string is succeeded by a delicious feeling of renewed health and vitality. The dose of water is generally made too large; and, by diminishing this, and wearing one of the high-peaked or extinguisher caps now in use, to break the fall of the descending torrent upon the head, the terrors of the shower-bath may be abated, while the beneficial effects are retained.

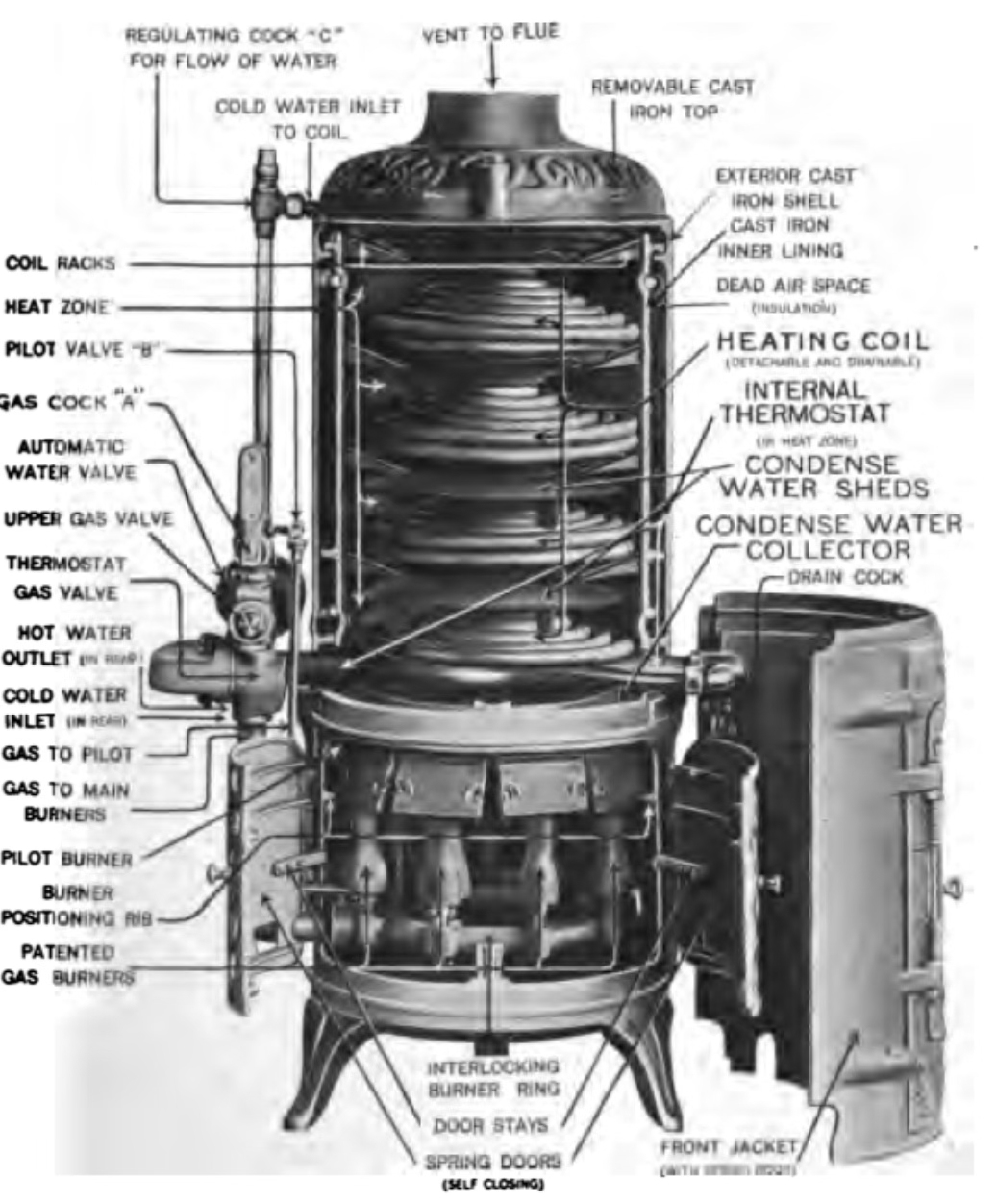

The age of the shower as an alternative to the bath really began towards the end of the 19th century (in wealthy households, at least) with the spread of indoor plumbing and, crucially, a means of heating that flowing water. In 1868 the English painter Benjamin Waddy Maughan invented a gas-powered instantaneous water heater, which he named The Geyser after the Icelandic watery eruptions. Unfortunately he forgot to include a flue to remove the heated gases so they would build up inside the device sometimes causing it to, err, explode! Nonetheless his work inspired the Norwegian engineer Edwin Ruud to invent the Ruud Instantaneous Automatic Water Heater in 1889, and by 1915 more than 100,000 had been installed in the USA alone (and yes, he included a flue to vent the gases).

Today the vast majority of people who have access to a shower will prefer it to a bath, with the Brazilians being their greatest fans of all, taking on average 14 showers each per week!

Another one of his papers is entitled: An account of the dissection of a child. Communicated in a letter to Dr. Brook Taylor.

The Ninewells Hospital in Dundee has a road named after him. I hope that they were not aware of what he got up to when they made that decision…

Or to give it its full title, Lectures on Diet and Regime. Being a Systematic Inquiry Into the Most Rational Means of Preserving Health and Prolonging Life: Together with Physiological and Chemical Explanations, Calculated Chiefly for the Use of Families, in Order to Banish the Prevailing Abuses and Prejudices in Medicine. Which is a bit of a mouthful.

I spent far too much time attempting to find the origin of the 1767 date, to no avail. My best guess is that someone confused the date of Feetham’s birth with the date of the patent, and that then, as is often the way online, got endlessly repeated.

Fascinating per usual. I am impressed by how each of these entries is engaging, well-researched, and insightful. Really strange histories.

A fascinating history! Thank you!