(Apologies in advance that, due to the nature of this topic, things will get a little scatalogical at times.)

Toilet paper is one of those mundane, ubiquitous items that few people pay any attention to. Its importance to our daily lives was, however, clearly demonstrated when it became the first product that UK shops sold out of in the panic buying at the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, and so I thought that it would be interesting to dig into its history.

As with shampoo, toilet paper is something that began to be used in the western world long after it had been developed in the east. So I’ll begin by looking at how people cleaned their bottoms before paper became commonplace. Some of you may know that at their communal latrines the ancient Romans had a device that was a sponge on a stick, called a xylospongium or tersorium, that was deployed for the purposes of anal hygiene. The sponges were washed in a mixture of water and vinegar between usages and were within easy reach of the people doing their business. Except that might not be true at all. We actually don’t know for sure what the sticks were used for, and some historians believe that they were instead used for clearing blocked pipes. This theory may be supported by the (very unpleasant) story recounted by Seneca about a gladiator using one to commit suicide.

…lignum id, quod ad emundanda obscena adhaerente spongia positum est, totum in gulam farsit (the stick, on which a sponge is placed for the cleaning of stuck filth, he stuffed all the way into his throat)

We do however know that seashells, moss and leaves were being used for such ablutions at the time, and fragments of cloth found in the sewers of Herculaneum suggest that this too could have been an option, but only for the wealthiest families. The Greeks (in a practice later adopted by the Romans) were meanwhile using fragments of pottery called pessoi (pebbles). These most likely started out as bits of broken ceramic that then had their edges rounded to create a smooth, non-injurious, surface for scraping. The Greeks even had a proverb relating to their use: “Three stones are enough to wipe one’s arse.”1 In some cases names have been found written on surviving pessos which have been speculated to be those of the enemies of the user as a way to denigrate them!

At around the same time on the other side of the world bamboo sticks with cloth-wrapped ends – called variously salaka, cechou and chugi – were being used for bottom cleaning in China and Japan; 2,000-year-old examples of them have been found in the ruins of way-stations along the Silk Road. It wasn’t long before that great Chinese invention paper was being employed for the same purpose. The first reference to the use of toilet paper dates back to 589 AD in the writings of the scholar Yen Chih-Thu who noted, “Paper on which there are quotations or commentaries from the Five Classics or the names of sages, I dare not use for toilet purposes.”

While we may consider the use of paper a considerable step up in hygiene terms from sponges on sticks or bits of old pot this was not a universally held belief. In the Middle East it was customary to cleanse oneself using water and a hand (typically the left). In 851 the Arab writer Abu Zaid Hasan al Siraff wrote of the Chinese custom:

They do not take care for cleanliness and they do not wash themselves with water after paying a call of nature, but they only wipe themselves with paper.

This did not stop the Chinese though as by the 14th century they were producing an estimated 10 million packets of toilet paper a year. A vast amount, to be sure, but given that the population of the country was around 100 million people at the time this was still the preserve of the wealthy. In 1393 it was recorded that the imperial court alone used 720,000 sheets, each one around two feet by three feet (60 by 90 centimetres).

As Europe moved into the Renaissance, paper use in water closets increased among the wealthy there too – though they weren’t using a product specifically manufactured for this purpose. Rather they took advantage of the surge in production of printed books, often in combination with religious schisms. Martin Luther (a man noted for his intestinal troubles) was said to keep copies of books by his enemies in the lavatory and tore pages from them to use. The dissolution of the monasteries in England in the 16th century enabled people to buy ‘heretical’ books on the cheap and use them in a similar manner. John Bale, Bishop of Ossory in Ireland, wrote in 1549:

A great nombre of them whych purchased those superstycyous mansyons, reserued of those lybrarye bokes, some to serue theyr iakes, some to scoure theyr candelstyckes, and some to rubbe their bootes.

Seventeenth-century England was awash with pamphlets and handbills which provided even the poorest in society with paper which could be repurposed and this was fittingly referred to as “bum-fodder” – an expression that survives today in the form of the word bumf (or bumph), meaning unwanted printed materials such as advertising fliers. An early reference to bum-fodder can be found in a book entitled An easy Entrance to the Latin Tongue2 dating from 1649 (the fact that it was deemed important enough to be included in a translation guide suggests wide usage at the time).

Not everyone thought that paper was a comfortable option however. François Rabelais in his, err, Rabelaisian novel Gargantua and Pantagruel has the titular Gargantua declaim “Who his foul tail with paper wipes, Shall at his ballocks leave some chips”. The giant goes on to describe his preferred alternative:

I say and maintain, that of all torcheculs, arsewisps, bumfodders, tail-napkins, bunghole cleansers, and wipe-breeches, there is none in the world comparable to the neck of a goose, that is well downed, if you hold her head betwixt your legs. And believe me therein upon mine honour, for you will thereby feel in your nockhole a most wonderful pleasure, both in regard of the softness of the said down and of the temporate heat of the goose, which is easily communicated to the bum-gut and the rest of the inwards, in so far as to come even to the regions of the heart and brains.

The English continued to prefer using books well into the 18th century, as a letter written by Lord Chesterfield to his son (published in 1747) demonstrates. In it he describes that bathroom habits of a gentleman of his acquaintance, noting in particular their efficiency:

He bought, for example, a common edition of Horace, of which he tore off gradually a couple of pages, carried them with him to that necessary place, read them first, and then sent them down as a sacrifice to Cloacina; thus was so much time fairly gained …

In America a less highfalutin tome was put to the same use by hundreds of thousands of people. The Old Farmer’s Almanac has been published continually since 1792 and is a compendium of weather forecasts, gardening and farming advice, folklore and future trends. Fairly early on in its productions its readers, most of whom lived in rural settings, took to keeping their copy on a nail in the outhouse, reading a few pages then ripping them out and deploying them as needed. Rather than be dismayed by how his book was being treated, the founder, Robert Bailey Thomes, leant into it, and started drilling holes in the corners of the volumes to make it easier to hang in the loo. The holes persist to this day, though there was a plan to remove them in the 1990s (as they added $40,000 to the cost of publication) but a survey of their readers showed huge support for the holes, and so they were retained!

It wasn’t until 1857, more than 1,000 years after it had been available in China, that Americans first had the opportunity to buy specifically designed toilet paper. On the 9th of December Joseph Gayetty launched “Medicated Paper, for the Water-Closet” in New York. The sheets were impregnated with aloe, to add lubrication, were pitched as a cure for haemorrhoids, and retailed at 50 cents for 500 sheets. Equating historic prices to today’s values is a notoriously tricky business, but given that the average daily wage for a labourer in 1857 was about $1 and today it is around $17 per hour, or $130 per day, that works around at a princely $65 a pack!

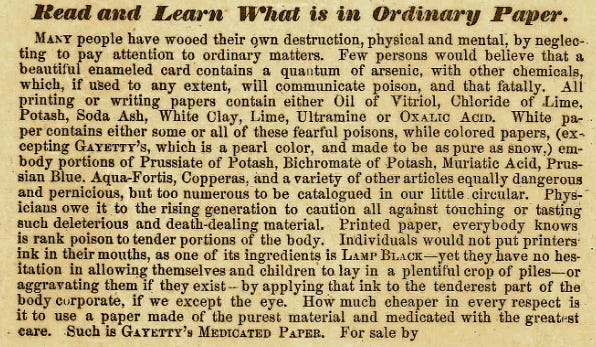

This cost was significant – why pay so much when you could use the pages of the Old Farmer’s Almanac effectively for free? Gayetty’s approach was, frankly, to fearmonger about the risks of using the “death-dealing” alternatives: “Printed paper, everyone knows, is rank poison for the tender portions of the body”!

Much play was also made of the softness and absorbency of toilet paper when compared to the hard, shiny pages that one might use otherwise. Despite this, Gargantua’s complaint about paper seems to have held true into the 20th century. As late as the 1930s, Northern Bath Tissue was proudly advertising itself as “Splinter Free!”.

I’d like to close by mentioning a rather interesting use that toilet paper was put to by the Allies during the Second World War. Jokes and cartoons were printed on the paper to amuse the troops as they went about their business, some of them topical – such as the portrait of Hitler captioned “Now I’m a brownshirt all over!”. The Izal company even employed a poet to pen inspiring poems for inclusion on the sheets, like this one:

Hitler now screams with impatience

Our good health is proving a strain

May he and his Axis relations

Soon find themselves right down the drain.

Not likely to win the Nobel Prize for Literature, I suspect, but it probably raised a few smiles on the front lines!

The rightly forgotten 1993 Sylvester Stallone movie Demolition Man sees our hero awake in the far distant future of, err, 2032. He is bewildered to discover that toilet paper has been replaced by three shells. Unlikely as it may seem, I think that this must be some kind of reference to that proverb. Did I rent the film, 31 years after having seen it in the cinema, to check this fact? Yes. Did I regret that decision? Yes. Did I abandon the film part-way through? Also yes.

Or to give it its full title, An easy Entrance to the Latin Tongue: wherein are contained, the grounds of grammar, ... a vocabularie of common words English and Latine, etc. Aditus facilis ad linguam Latinam, etc. Which is a bit of a mouthful.

Fascinating thanks! Bumpf makes so much sense now 😂

This is a widely entreating post! The history of what we perceive as ordinary is often really interesting. I had not really thought about why TP rolls have a hole in the middle and now I'll never see a roll without thinking about this. Good scholarly work changes how readers see the world!

I only wish there was more to read even if digital pages have no other use.

I wonder all the kinds of meaning making associated with the use of toilet paper. Which classes used what, and for what purpose? Was it common to buy your rivals books to defecate on them? Did people put TP on guest wash basins as a sign of prestige... What categories of people first adopted these behaviors. Interestingly with the bidet and "smart toilets" some people have moved away from using TP. What does this mean?