A history of… deodorant

Would you rather smear yourself in burnt goats' horns or wear a cone of fat on your head?

Let’s be honest about it: humans smell. Actually we smell in different ways and for different reasons. We probably emit pheromones1 – scents which are unique to each of us and which are linked to our individual genetics. Pheromones play a significant role in some other mammals. Mice, for example, are less attracted to other mice that have similar smells. This is because the scent is linked to the immune system and hence genetics and it is generally a bad idea to mate with something that is genetically similar to you (think marrying cousins). An experiment was tried in the 1990s in Norway with humans whereby women had to assess the slinkiness of T-shirts worn by various men and then their genetics were compared. This showed that the more genetically dissimilar to the women the men were, the less offensive their smelly clothing – mimicking the behaviour of the mice. Sadly, though, this experiment has yet to be repeated. But today I want to explore a different type of human smell, and our attempts to prevent and mask it using deodorant.

Humans produce two different kinds of sweat, from two different types of glands. The eccrine sweat glands cover most of our body and produce a watery odourless sweat (think of the beads of sweat that form on your forehead). Then there are the apocrine sweat glands that are found in our armpits and around our groins. The sweat they produce is more oily and contains waste proteins, carbs and fatty acids. It may surprise you to learn that this sweat doesn’t have much of a scent either; the reason that armpits get smelly is because the bacteria that live there ferment the sweat and the resulting products are, frankly, rather rank.

Before the arrival of clothing, this wasn’t much of an olfactory problem – underarm hair is pretty good at wicking away moisture and the resulting environment was too dry for the bacteria to thrive in. Once we started wearing clothes, however, we created nice, moist nests that are perfect for bacteria to start pumping out stench, and for thousands of years humans have sought ways to remove or mask it. One of the approaches taken by the ancient Egyptians was to shave off their underarm hair, and this proved to be surprisingly effective. As scent expert Dr Tristram Wyatt2 explains:

There is something about shaving your own pits that reduces the smell dramatically, and the reason for that is that most of the smell comes from bacterial breakdown of molecules that are secreted by specialised scent glands in the armpit. So one of the things about shaving your armpits is because the bacteria live on the hair. If you clear cut your rainforest, cut them all down, you basically take away the habitat.

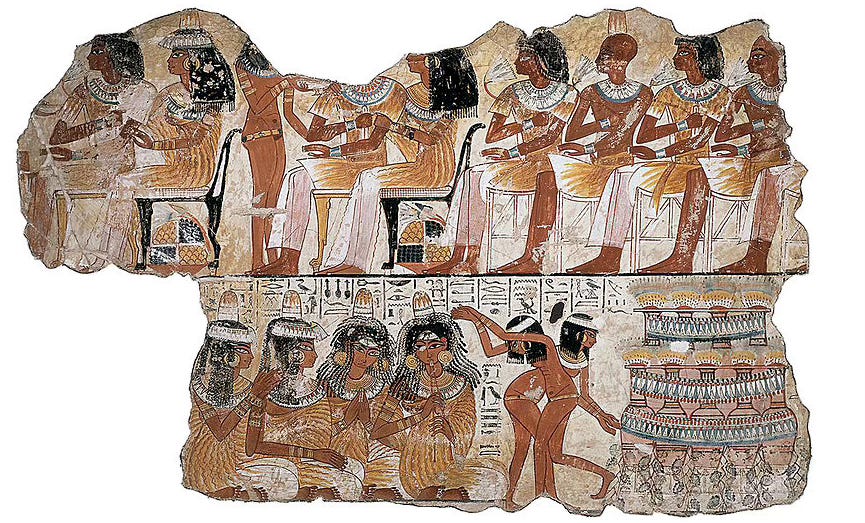

Armpit shaving is however both time consuming and risky – in the days before antiseptics and antibiotics a small nick in the skin could lead to a serious infection. Egyptians would therefore also apply scented oils to mask the smell. There was though the problem that the perfume would wear off over the course of the day, so they came up with an ingenious (some might say bonkers) solution. It was to, err, strap a cone of scented animal fat to one’s head and, as it melted, smear the fresh supply of scented gunk over oneself (or just let it trickle down of its own accord)! These were known as ‘head cones’ (or ‘perfume cones’) and the earliest images of them date from the reign of Hatshepsut some 3,500 years ago. They are clearly visible being worn in the image below, along with brown streaks on the previously white clothing caused by streams of melting fat.

The ancient Romans were, of course, famous for their bathing rituals as a means of remaining clean and scent free, but they also had proto-deodorants. Pliny the Elder was a big fan of using rue (also known today as ‘herb of grace’ and still used in some places as incense) noting that:

Among the other properties which are attributed to rue, it is a singular fact, that, though it is universally agreed that it is hot by nature, a bunch of it, boiled in rose-oil, with the addition of an ounce of aloes, has the effect of checking the perspiration in those who rub themselves with it

Though he does go on to say that it is also effective in, err, reducing nocturnal emissions in men who are “subject to lascivious dreams” so his basis may not be wholly scientific. If you can’t get your hands on any rue he offers up an alternative:

Too profuse perspiration is checked by rubbing the body with ashes of burnt goats' horns mixed with oil of myrtle

It would be easy to dismiss Pliny’s suggestions as outdated folk remedies but his final one that has a credible scientific basis. He recommends the use of alumen (or ‘alum’’) as an antiperspirant. Alum is sulphate of aluminium… which is used in most modern deodorants!

Liquid alumen is naturally astringent, indurative, and corrosive: used in combination with honey, it heals ulcerations of the mouth, pimples, and pruriginous eruptions. The remedy, when thus used, is employed in the bath, the proportions being two parts of honey to one of alumen. It has the effect, also, of checking and dispersing perspiration, and of neutralising offensive odours of the arm-pits.

The collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the fifth century led to a significant decline in the personal hygiene of Europeans. In part this was due to the lack of bathing infrastructure and access to nice-smelling things, but there was also a religious element at play. While some bathing did still take place, it risked being associated with vanity, and hence sinfulness. St Jerome (347–420) was very much of this view, writing to the hermit Heliodorus:

Is your skin rough and scaly because you no longer bathe? He that is once washed in Christ [i.e. been baptised] needs not to wash again

Some mediaeval peoples were more attentive to their personal appearance than others. If you watch modern dramas you would be forgiven for thinking that the Vikings were a filthy, stinking bunch whereas the opposite was actually true. So much so that the smellier Anglo-Saxons were worried about the impact this might have upon their relationships, as the chronicler John of Wallingford noted in the 13th century:3

The Danes made themselves too acceptable to English women by their elegant manners and their care of their person. They combed their hair every day, bathed every Saturday, and even changed their garments often. They set off their persons by many such frivolous devices. In this manner, they laid siege to the virtue of the married women and persuaded the daughters, even of the nobles, to be their concubines.

The scholar Alcuin even blamed the sack of the monastery on Lindisfarne (793) on Christians emulating the hygiene regimes of their Viking invaders and so invoking the wrath of God!

Consider the dress, the way of wearing the hair, the luxurious habits of the princes and people. Look at your trimming of the beard and hair, in which you have wished to resemble the pagans. Are you not menaced by terror of them whose fashion you wished to follow?

Moving through the Middle Ages and into the Renaissance, there is a general view that people were, well, filthy most of the time. While it is true that people didn’t bathe in the sense of immersing their whole bodies in water – gathering, let alone heating, the volume required would have required vast effort – they did wash regularly using basins of water and soap. Related to this is the famous claim that Queen Elizabeth I “took a bath once a year whether she needed to or not” which despite being quoted in history books is wholly bogus. Her father, Henry VIII, had a bathroom in Hampton Court Palace that had hot and cold running water, and a dedicated steam room!

In the Georgian era full immersion bathing became more common amongst the well-to-do but hand scrubbing was still done every day. The monied classes could similarly remain somewhat fresh by regularly changing their undergarments. These were generally linen or cotton and close fitting and so were effective at wicking away sweat and removing odours through replacement. Nonetheless the ballroom at the end of a long night of dancing would undoubtedly have had a bit of a whiff about it!

Modern deodorants work by preventing sweating (though the blocking of the pores) and/or by creating an environment where bacteria can’t flourish, and they were invented really very recently. Now this is where some of the history you might find online is wrong or confused due to errors in the Wikipedia article about deodorant (I know, errors on Wikipedia, can you believe it?) that have been lazily cut and pasted. In 1888 the first commercial deodorant, Mum, was launched. The inventor is unknown, and the name is said variously to be taken from the nickname of the anonymous chemist's nurse or from the phrase ‘mum’s the word’ (armpits being something people didn’t want to talk about). It was a cream based upon zinc oxide to kill the smelly bacteria, and was not hugely successful – though the brand flourished in later years and is a market leader today. The first commercial antiperspirant (i.e. a product that actually stopped sweating, rather than killing bugs or masking smells), Everdry, launched in 1903. Like its Roman forebears it used an aluminium compound to block the pores, but it too failed to set the world on fire, partly because it was so acidic it would eat through clothes…

The game-changer in this story is a woman named Edna Murphey who was still a high-school student when she got into the business in 1910. Her father was a surgeon and had taken to using a product developed by a colleague that stopped his hands sweating during operations. Young Edna tried it on her pits and was delighted by the results. She borrowed $150 from her grandfather, named the product Odorono’ – aka ‘Odor? Oh No!’ – and got to work. She started selling it in earnest at the 1912 Atlantic City Summer Exposition where the heat of the summer created an eager customer base – customers who then acted as advocates for the product once they returned to their home states. Edna managed to clear $30,000, an incredible sum at the time, but there was still a barrier to her success. Like toothbrushes, her product was solving a problem that people didn’t realise that they had. Sweat was considered a part of everyday life and to counter it women would have ‘dress guards’ – cotton pads or rubber patches to stop their perspiration soaking their clothes.

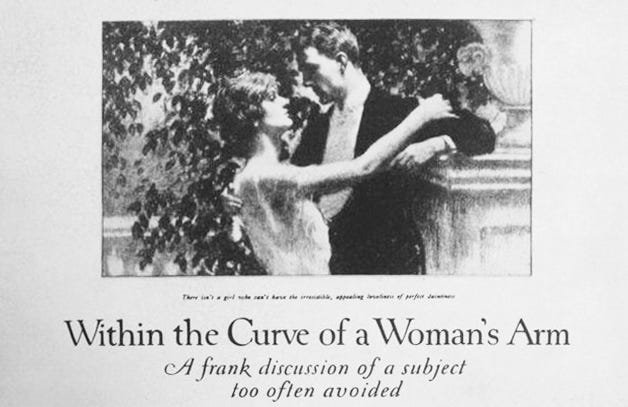

Undeterred, Edna hired the J. Walter Thompson advertising agency where she was paired with door-to-door Bible salesman turned copywriting superstar James Young. Young hit upon the strategy of making armpit sweat something that women should be embarrassed about, even a medical problem. The apotheosis of his art is probably an advert that ran in the Ladies Home Journal in 1919 with the title ‘Within the Curve of a Woman’s Arm, a frank discussion of a subject often avoided’. The ad continued:

A woman’s arm! Poets have sung of it, great artists have painted its beauty. It should be the daintiest, sweetest thing in the world. And yet, unfortunately, it isn’t, always.

This approach certainly created waves. “Several women who learned that I had written this advertisement said they would never speak to me again – that it was ‘disgusting’ and ‘an insult to women,” recounted Young, and apparently 200 women cancelled their subscriptions as a result. The ad man, however, was unabashed: “…but the deodorant’s sales increased 112% that year,” he continued.

Edna, who sold her company in 1928 to Northam Warren and Co. and married the muralist Ezra Winter,4 was surprisingly modest about her success:

Any girl could do what I did. Pure pride and stubbornness and obstinacy made me stay by something I had started. … the only credit I take is for hanging on over the rough places.

So the next time you are on a train in the height of summer, or in a hot theatre, please raise a small vote of thanks to Edna Murphey for making the atmosphere if not pleasant, then at least bearable.

The science is inconclusive at present.

Dr Wyatt was one of my tutors many years ago (which may explain the excess of science in this piece). I bumped into him at the party of a mutual friend some 30 years later and he explained the armpit-shaving approach to me in some detail.

He used this as a justification of the slaughter of the Danes in England in 1002!

I am being a pedant, but the Rockefeller Centre has got his dates wrong: he died in 1949, committing suicide after a fall from a gantry left him unable to paint.

Head cones - I think the Body Shop should carry these. non animal fat versions of course.

Another wonderful study of an everyday object, amazing work.