A history of… the toothbrush

The Roman method of tooth-whitening is unlikely to catch on today…

“Oh, I wish I’d looked after me teeth!” wrote the British poet Pam Ayres in the 1970s (her amusing verses were a staple of many a junior-school lesson). The British have something of a poor track record in dental maintenance, at least in the eyes of our American cousins, so some may be surprised to learn that the toothbrush is widely said to be a British invention. Well, err, actually, no. As with most historical things it’s not as simple as that, so today I am going to delve into the history of this humble bathroom essential.

First let’s look at what people used to keep their teeth clean before the invention of the toothbrush. It is broadly agreed that humans really started to have problems with their teeth when they moved away from the diverse, protein-rich diet of hunter-gatherers to the much more carbohydrate-heavy one of agrarian societies (bacteria such as Streptococcus mutans are pretty good at turning carbs into acids which contribute to tooth decay). This doesn’t mean that pre-farming societies didn’t attend to their oral hygiene: grooves worn into the teeth of both early humans and Neanderthals show that toothpicks were in wide use to remove detritus stuck between their choppers. A whole array of different materials were used as picks, from the obvious twigs and shards of bone through to feathers and even porcupine quills.

Dentistry, it turns out, is staggeringly old. A molar from the skull of a 25-year-old man who died fourteen thousand years ago bears the marks where a section of decayed tooth was chipped and cut out (his other teeth were fine, by the way). The use of drills on teeth dates back at least 9,500 years, and the oldest known filling, made of beeswax, was found in a 6,500-year-old tooth from Slovenia. It wasn’t much later, around 5,500 years ago, that we find evidence of the first objects that can be said to be akin to toothbrushes.

In ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia twigs were cut from the plant Salvadora persica (also known as the ‘toothbrush tree’). The ends were chewed, which frayed them and turned them into brushes which could then be used to scrub the teeth. These twigs not only taste good; they are a source of natural fluoride, which helps to prevent tooth decay and promote the rebuilding of teeth enamel. These twigs, called miswak, are used across the Arabian peninsular, Africa and South Asia to this day. The prophet Mohammad was a big fan, saying this about them:

Use the Miswaak, for verily, it purifies the mouth, and it is a Pleasure for the Lord. Jib-ra-eel exhorted me so much to use the Miswaak that I feared that its use would be decreed obligatory upon me and upon my Ummah. If I did not fear imposing hardship on my Ummah I would have made its use obligatory upon my people. Verily, I use the Miswaak so much that I fear the front part of my mouth being peeled (by constant and abundant brushing with the Miswaak)

This twig-based approach to dental hygiene was also employed in Rome and Greece (though other trees, such as olive and cinnamon, were also used). The Romans were also big fans of toothpaste (though they didn’t invent it, 5,000 years ago the Egyptians were using tooth powders made from such things as ground up ox hooves, myrrh and powdered and burnt eggshells). As well as having an abrasive paste for cleaning as the Egyptians did, the Romans went one step further though and developed the first whitening toothpaste to make their gnashers more attractive. This was made from a combination of milk and, err, human urine (the ammonia it contained acting as a bleach) and I fear it wasn’t the most lovely taste in the world!

As Europe slid into the Dark Ages, dental care took a downward turn. Tooth cleaning, where it happened at all, generally took the form of rubbing the teeth with some soot, sand or ground-up shells, applied with the fingers or a bit of rag. Twig-chewing continued in much of the rest of the world though as the Chinese monk Yijing recorded in the seventh century:

Every day in the morning, a monk must chew a piece of tooth wood to brush his teeth and scrape his tongue, and this must be done in the proper way. Only after one has washed one's hands and mouth may one make salutations. Otherwise both the saluter and the saluted are at fault. In Sanskrit, the tooth wood is known as the dantakastha—danta meaning tooth, and kastha, a piece of wood. It is twelve finger-widths in length. The shortest is not less than eight finger-widths long, resembling the little finger in size. Chew one end of the wood well for a long while and then brush the teeth with it.

It was in China too, during the Tang Dynasty (619–907), that the earliest known toothbrushes were in use. These were made from hog bristles (sourced from hogs living in colder climes as these were stiffer) affixed to bamboo handles.

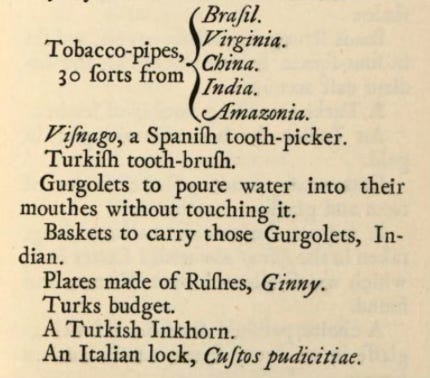

Sometime during the 16th or early 17th century European travellers spread this useful invention back to Europe, though generally these brushes used horse hair, rather than hog’s bristles as they were softer and easier on the gums. If you search online you will likely be told that the first reference in English to the toothbrush is from the diaries of my fellow Oxford resident, the great antiquarian Anthony Wood, who records buying one from a Mr J. Barret in 1690. Actually the catalogue of the Musaeum Tradescantianum (the collection of curiosities assembled by John Tradescant Snr.) published in 1653 lists one:

After his son’s death the collection was acquired1 by Elias Ashmole so presumably said brush is in the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford today!

The production of toothbrushes was very much a cottage industry until one William Addis came along. A rag trader, he was arrested in 1770 for participating in a riot in Spitalfields. While incarcerated he was inspired by the broom in his cell to invent a device for brushing teeth that could replace the soot and rag approach he had previously been using. He kept a bone from a meal, drilled holes in it, pushed bristles through them and created a toothbrush! In 1780 he then began mass producing the things and became astonishingly wealthy. At least, that is the story told on the website2 of the company that still bears his name. Personally, I don’t believe a word of it. For starters, the Spitalfields riots took place between 1765 and 1769 and while they could have got the year wrong, the notion that he had a flash of inspiration and created this wholly novel thing (and then waited a decade before producing it) is clearly completely bogus. Wood was able to pop into a shop in Oxford 80 years earlier and simply buy a toothbrush – they were widely known and widely used!

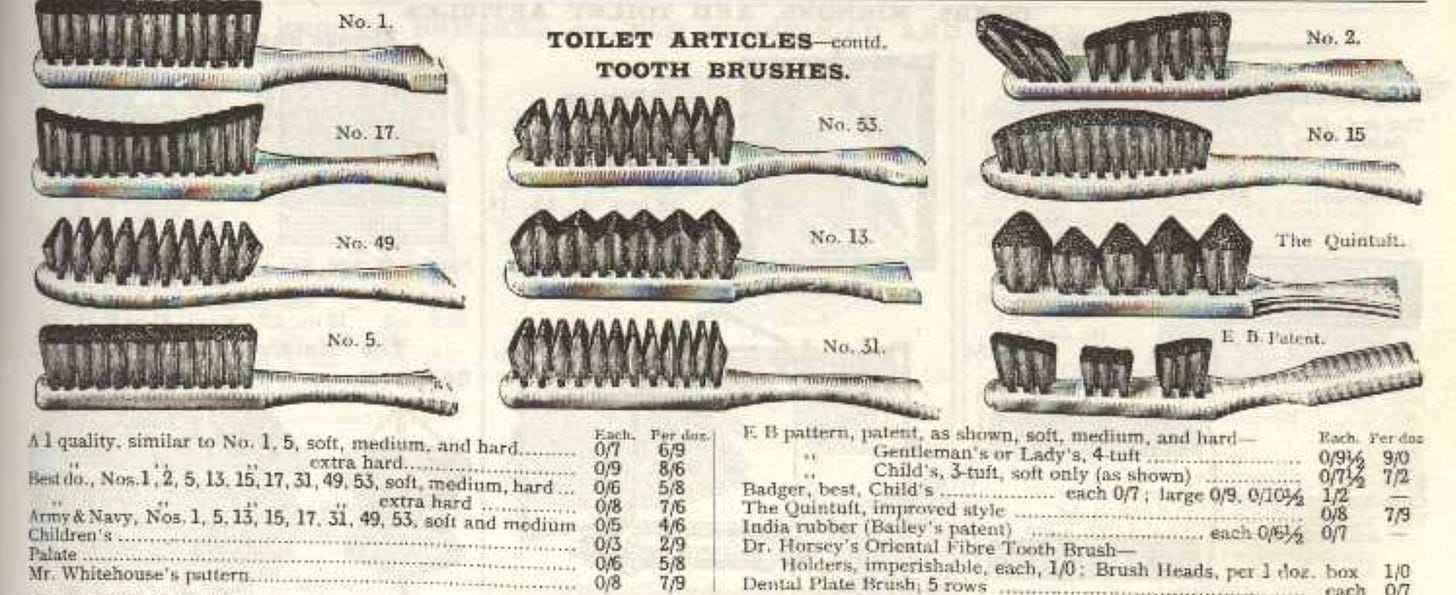

To give Addis his due, he was the first person to really start manufacturing the brushes at scale. By the time his son took over there were 60 people employed just in the manufacture of the bone handles (cow thigh bones were used and cut into appropriately sized pieces). A network of piece-workers across London were then employed in the drilling, threading and glueing of the bristles into the handles.

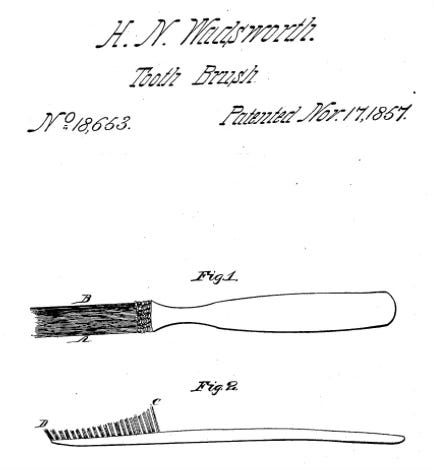

The first patent for a toothbrush in the USA was issued to H. N. Wadsworth in 1857, who hit upon the idea of having a curved set of bristles to allow for more effective cleaning of the teeth.

My invention embraces the following features to wit: lst, the concave form of the surface of the bristles as represented from A to B Figure l. 2d, the circular form of the surface of the bristles as represented from C to D in Fig. 2d. 3d, the projection of the bristles beyond the end of the brush as represented in Fig. 2d at letter D, and which projection improves the brush by being at a still greater acute angle with the back. 4th, the wedge-shaped back as represented in the drawings and described in the specification, for the purpose of allowing the brush to penetrate thoroughly under the muscles of the cheek and around the back or molar teeth.

One surprising fact that I learned in researching this piece was, despite the ready availability of brushes, how infrequently Americans brushed their teeth at the start of the 20th century. A figure that I have seen often cited (but cannot robustly source) is that only 7% of US households had toothbrushes in the early 1900s. By the 1930s, however, 65% of Americans were brushing their teeth daily,3 and this can be largely attributed to the actions of an ad man named Claude Hopkins.

Hopkins was approached by the creators of Pepsodent toothpaste to launch their product, and gave him a compelling incentive – the option on a chunk of stock in their company. Previous dental campaigns had largely focused upon the health benefits of tooth-cleaning, framing the activity in terms of avoiding decay. Claude took a totally different approach; rather than brushing preventing a negative he framed it as promoting a positive:

Note how many pretty teeth are seen everywhere, millions are using a new method of teeth cleansing. Why would any woman have dingy film on her teeth? Pepsodent removes the film!

The use of the word ‘film’ in the context of teeth was also a Hopkins invention. Reading through dental textbooks as part of his research he recalled:

It was dry reading, but in the middle of one book I found a reference to the mucin plaques on teeth, which I afterward called “the film”

This approach was hugely successful for both Pepsodent and Hopkins – he earned more than a million dollars from his work, at a time when labour might be making five dollars a day!

One problem that all of these early toothbrushes shared is that they used various kinds of animal hair that are covered in microscopic scales and often, as is the case with horsehair, are hollow. These provide perfect breeding spaces for bacteria and hence the act of cleaning the teeth with such brushes could also serve to spread infections around. This problem was solved with the introduction of nylon bristled toothbrushes by DuPont in 1938, creating the product that we use to this day.

In his excellent book Luxury Fever Robert Frank makes the observation that one can walk into a supermarket in America and for less than $204 purchase a bottle of wine “...far better than the wines drunk by the kings of France in centuries past”. While I love access to affordable, royalty-beating wine, I appreciate modern dental treatment even more. By way of example I’d like to end by talking about the teeth of Louis XIV, the Sun King, probably the richest and most powerful person on the planet at the time.

Louis’s teeth were, not to put too fine a point on it, rotten. This was a combination of both poor oral hygiene and also his love of sugar. In 1685, at the age of 47, he need to have some particularly troublesome teeth removed. Things did not go well: in the process a chunk of his jaw was ripped out along with part of his palate. The resulting hole meant that whenever he drank, liquid would seep out of his nose. The area was eventually cauterised with a red-hot poker, but his teeth continued to fail and be removed, and he was left toothless, on a liquid diet, with decaying detritus in the holes where his teeth once sat. If that doesn’t encourage you to make sure you visit your dentist regularly I don’t know what will!

Some less forgiving people say “stolen”.

The site describes this invention as “the world’s first toothbrush” which is clearly nonsense! Also, where did he get the bristles from in his cell? How did he drill the holes? How did he stick the bristles to the handle?

You will often see it stated online that tooth-brushing only became prevalent in the US after WW2 due to returning GIs (who had to brush their teeth every day) instituting the practice back home. This is not true.

In his book it is $10 but I have adjusted for inflation from the publication date.

Wonderful story of an ordinary object told in an engaging manner! Thank you.