First let’s consider what shampoo actually is. Obviously it is something used for the cleaning of hair. More specifically it is designed to remove the oils (sebum) that build up in the hair, but not to the extent that the hair becomes damaged and hard to manage. Is shampoo the same as soap? Yes, kinda, but it is a bit complicated.

Both shampoos and soaps contain a surfactant which reduces surface tension, separating dirt and oil from skin and hair, and binding to it. Today shampoos and some soaps (particularly liquid soaps and body washes) are made from the same ingredients, but hard soaps are made from different stuff.

Soap is made by combining an alkali and animal or vegetable fats to create surfactants in a process called saponification. Originally the ash from fires was used as the alkali; indeed the earliest record of a chemical reaction was found on a Sumerian clay tablet dating from 2,500 BC describing how to make soap by heating a combination of oil and wood ash. The resulting product could be used for washing hair, but it wasn’t ideal as it remained fairly alkaline – our hair and scalps are somewhat acidic, so using alkalis on them can damage both the skin and hair.

The first true shampoos started to be used in the Indus valley more than 4,000 years ago. They were created by boiling up the fruits of sapindus (also known as soapnut) plants along with dried Indian gooseberries. The resulting concoction contained natural surfactants without any of that pesky alkali which made it perfect for washing hair. The Chinese too had a form of shampoo. At least as early as the Tang dynasty (618–907 AD) they were using rice water (which also contains a small amount of natural surfactants) to wash their hair.

In the 18th century colonial traders became enamoured with the practice of daily hair washing and massage they encountered on their travels and were the first to bring the concept of shampoo back to Europe. The word ‘shampoo’ has been dated back to 1762 and is derived from the Hindi word cā̃pō (चाँपो), which is itself derived from the Sanskrit root chapati1 (चपति), which means 'to press, knead, or soothe’.

The first usage in Europe of the word shampoo was not actually about hair-washing however but rather massaging that accompanied it. The traveller Charles Frederick Noble wrote in 1765:

Shampooing is an operation not known in Europe and is peculiar to the Chinese, which I had once the curiosity to go through, and for which I paid but a trifle. However, had I not seen several China merchants shampooed before me, I should have been very apprehensive of danger, even at the sight of all the different instruments that were arranged in proper order on the table before the operator began.

He first placed me in a large chair, then began to beat with both his hands very fast upon all parts of my body. He next stretched out my arms and legs, and gave them several sudden pulls that racked my joints; then got my arm upon his shoulder and hauled me sideways a good way over the chair; and as suddenly gave my head a twitch or jerk around, that I thought he should have put my neck out of joint. Next he beat with the ends of his fingers very softly, but very quickly all over my head, body and legs, every now and then cracking his fingers with an air: then he stroked up my ears, temples and eye lashes; and again racked my joints.

After he had gone through this process he proceeded with his instruments to scrape, pick and syringe my ears, every now and then tinkling with an instrument close to my ears. The next thing was my eyes; into which I patiently suffered several small instruments to be thrust and turned about; by which operation, he brought away half a teacupful of hot, waterish stuff. this was not only the most painful, but the most dangerous part of the whole operation which made me afraid to make the least motion with my head lest I should have suffered more; so I sat with resolute patients, till he pulled out these instruments and was about to use others to my eyes, but I had suffered so much that I would not permit him to meddle with them any farther.

How had Europeans been washing their hair in the meantime? The Gauls and Germanic tribes were soap users, but in the former case it was used on the hair as much to change its colour as to keep it clean. As Pliny the Elder wrote:

The people of Gaul, when hunting, tip their arrows with hellebore, taking care to cut away the parts about the wound in the animal so slain: the flesh, they say, is all the more tender for it. Soap, too, is very useful for this purpose, an invention of the Gauls for giving a reddish tint to the hair. This substance is prepared from tallow and ashes, the best ashes for the purpose being those of the beech and yoke-elm.

For the Romans themselves hair-care generally involved combing and oiling it, with the occasional washing using water and sometimes vinegar or lemon juice. One time of the year they were likely to wash their hair was the festival of Nemoralia, held between the 13th and 15th of August in honour of the goddess Diana. Plutarch wrote that those attending would carry out the “washing their hair before dressing it with flowers”.

Washing wasn’t really a big thing for most Europeans in the Middle Ages, and the washing of the hair even less so. More attention was given to colouring, straightening and thickening the hair (and also to fruitless endeavours to combat baldness). The Trotula, a 12th-century Italian text on women’s medicine, offers the following advice:

So that hair might grow wherever you wish. Take barley bread with the crust, and grind it with salt and bear fat. But first burn the barley bread. With this mixture anoint the place and the hair will grow.

In order to make the hair thick. Take agrimony and elm bark, root of vervain, root of willow, southernwood, burnt and pulverised linseed, [and] root of reed. Cook all these things with goat milk or water, and wash the area (having first shaved it). Let cabbage stalks and roots be pulverized and let pulverized shavings of boxwood or ivory be mixed with them, and it should be pure yellow. And from these powders let there be made a cleanser which makes the hair golden.

I cannot imagine what the scent of bear fat would have been like, other than it was unlikely to have been pleasant, though as we shall see it was used for many centuries to come. What hair washing that did take place was either with a mixture of herbs and water, or using lye soap (with the hair being oiled afterwards to repair the damage caused by the alkali), but generally more attention was given to combing and braiding.

One of the things I love about researching these pieces is discovering quite how recent some commonplace things and practices are. Even by the 19th century, hair washing had not really progressed very much, though Lydia Child, writing in The American Frugal Housewife in 1829, did suggest a somewhat novel approach to hair washing using, err, rum. Specifically, New England rum!

I do wonder if there really was that much difference between using rum and brandy in hair-washing, as either seem likely to have been hugely effective (or pleasant) but not so much that I want to experiment for myself! In 1856 we still see our old friend bear fat being used in hair care, but by now using eggs for washing was all the rage, as described in this letter to The Monthly Magazine of Belle-lettres and the Arts:

A big innovation in hair-washing came in 1904 when the German chemist Hans Schwarzkopf invented a powder shampoo that could be dissolved in water which soon became popular in Germany (the brand he created, Schwarzkopf, is the same one you see on hair products today), but it took a while for such products to take off in the USA. So much so that the New York Times published an article in 1908 entitled ‘How to Shampoo the Hair’.2 The article begins:

It is hardly necessary to state that every woman likes to have her hair not only daintily and becomingly arranged but soft and glossy in appearance and texture. Whether the care of the hair be given over to one’s maid or hairdresser, or if one is obliged to keep it in order herself, the shampoo is a necessary part of the treatment, and the trouble is that very few people know how to wash the hair thoroughly.

The article goes on to explain, in some detail, how to perform an activity that most of us carry out every day without giving it a second thought. Though the fact that we wash our hair every day would likely come as something of a surprise to the author of this piece as they go on to note:

Several hair specialists recommend the shampooing of the hair as often as every two weeks, but from a month to six weeks should be a better interval if the hair is in good condition.

It may seem unthinkable today that one would only was one’s hair every six weeks, but well into the 20th century many people would treat their hair daily with pomades and oils. Probably the most famous of these is Macassar oil, originally produced from the Macassar ebony. It was popularised by, for want of a better term, an 18th-century celebrity hairdresser named Alexander Rowland who introduced Rowland’s Macassar Oil in 1793. This product, and others like it, lead to an invention which is one of my favourite words in the English language, the antimacassar. An antimacassar is a piece washable fabric or crochet placed on the back or arms of a chair or sofa to prevent oil from the hair staining the fabric beneath. Despite the reduction in use of such hair treatments you will still find antimacassars on airline and train seats to this day.

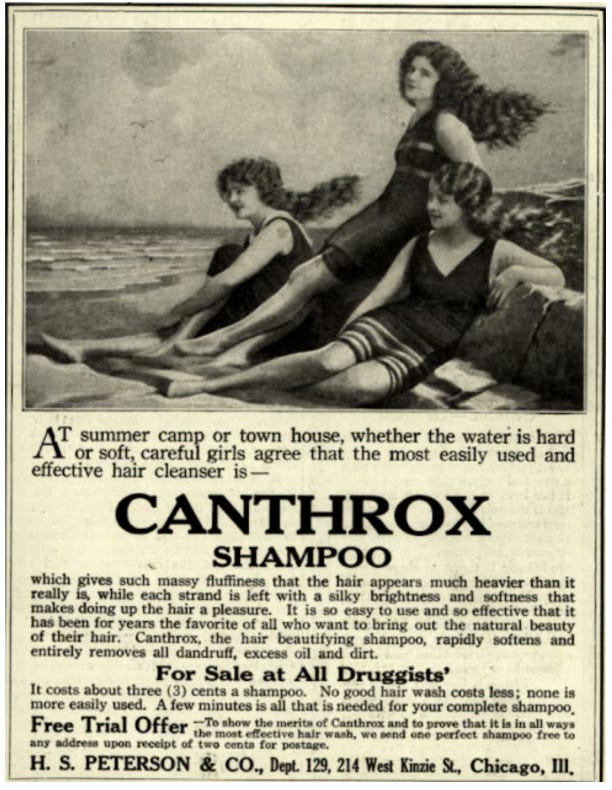

Shampooing really began to take off in the USA in 1909 when H. S. Peterson and Company launched ‘Canthrox’ shampoo. A box containing enough shampoo for 15 washes would set you back 50 cents (or around $16 in today’s money) and promised to leave your hair silky-soft and bright.

In 1927 the Schwarzkopf company (Hans having died in 1921, it was now run by his wife, Martha) introduced the first liquid shampoo but this, and all other shampoos, were still soap based, with the attendant alkali problems. It was six years later, in 1933, that a shampoo with non-soap-based surfactants was invented by the company, the first shampoo that is truly akin to the ones that we use today.

It wasn’t until the 1970s that daily hair washing became the norm in the USA, and this coincided with something of a backlash against the practice. The ‘no ’poo’ movement sprang up around this time, arguing that chemical shampoos stripped essential oils from the scalp and hair. This causes the body to create more oils, resulting in lanker, greasier, hair which then necessitates more washing with shampoo, hence more oils, in a vicious circle. The proposed solution is to forgo hair washing for six weeks to break this cycle, and then ideally only wash hair in clean water, or if necessary using baking soda and a solution of apple vinegar.

There was renewed interest in this approach during the Covid lockdowns (as people isolating were less worried about how others might judge their hair during the transition phase) and many reported very positive results. Though as a schoolmate of mine in the 1990s once went a month without washing his hair for a bet, and I saw the results first-hand, I think I’ll be staying in tonight. And washing my hair.

I initially thought “Oh, kneading, that is why the bread is also called chapati”. I was wrong. Chapati (the bread) is a derivative of Sanskrit root *चर्प (charpa) meaning ‘flat’.

Strangely it was combined with a piece explaining how to make German beer soup!

I always wondered why antimacassars were called that!

I remember an early household guru (Mrs Beeton?) recommending that hair be washed just once a month, but that hair brushes should be kept 'scrupulously clean', which makes some sense. Where can I buy some bear fat?