Uneasy situation, 1788

A good doctor's companion

On the same day that my last piece – on Janet Schaw and her blithe attitude towards slavery on her friends’ sugar plantations in the Caribbean – was published here, I was exploring literary London on foot. And my journey brought me to discover a very different story about attitudes to slavery, again from the 18th century.

My walk took me to the Dr Johnson’s House museum in Gough Square, tucked beneath the silvered monoliths of the City and the shady halls of the inns of court. I highly recommend this museum, which I was lucky to have entirely myself for a little while (a very different experience from the Charles Dickens Museum I visited on the same day, which is good but… busy). There I was, in Johnson’s garret, where his famous Dictionary was compiled, as if he had just shambled out of the room in search of a schooner of brandy.

One of the key figures in his life in that house was his manservant, Francis Barber – who was a former slave. A lot of the precise details of his life are quite elusive, though all credit to two people who have written biographies of him, Aleyn Lyell Reade in 1912 and Michael Bundock in 2015.1

Briefly, Francis was born into slavery sometime in the 1740s in Jamaica. As a child he was brought to England by Colonel Richard Bathurst, who was the father of one of Johnson’s close friends. He was given his freedom (in some sense) and an education, and eventually was given a job as Johnson’s servant shortly after the doctor’s beloved wife had died in 1752; other than brief stints working for a London apothecary and then a couple of years at sea with the navy, Francis remained at his side until Johnson’s death.

Samuel Johnson, to his great credit, was a vehement opponent of slavery, at a time when abolitionism was still quite a new thing. “No man is by nature the property of another,” he famously said, and he described Jamaica as “a place of great wealth and dreadful wickedness, a den of tyrants and a dungeon of slaves”. I don’t want to over-romanticise, of course: being freed from slavery into a life of domestic servitude is not what we might think of as freedom, and any relationship of this kind has an air of paternalism. But Johnson very clearly treated Francis with great respect and fondness, and his most renowned biographer, James Boswell, noted “his uncommon kindness to his servants” (and his cat, Hodge).

And perhaps most notably of all, Johnson made Francis (or Frank, as he called him) the main beneficiary in his will, including an annuity of £70 (perhaps £10,000 now). In 1773 Francis married 17-year-old Elizabeth Ball at St Dunstan in the West (a beautiful London church I visited on the same day as my museum visit) and had several children (including a Samuel) – in 1783, Johnson even welcomed the young family to live with him. Francis seems to have been well liked by many – with the notable exception of Johnson’s first biographer, Sir John Hawkins, who quibbled over the doctor’s generosity to Frank and was clearly a racist. When Johnson died in 1784, Francis moved to the doctor’s home town of Lichfield in Staffordshire and later became a village schoolteacher.

Sadly Francis left no diary, no memoir, and although he is mentioned in many contemporary sources (particularly Boswell’s Life of Johnson), his own words are few. In this (Victorian) painting of Johnson and his famous friends at Sir Joshua Reynolds’ house, a black servant passes in the shadows at the back. This might be Francis – but then, like the famous portrait of a young black man by Reynolds often said to be of him, it might well not be, not least because Reynolds also had a black servant. But the metaphor is apt: there, present at celebrated gatherings of literary luminaries, but barely visible.

But we can find snatches of Francis’ own voice and personality. On 15 July 1786, for example, James Boswell wrote to him at Lichfield to glean useful info about Johnson – and included what might be the first example of a biographer using a questionnaire:

Good Mr Francis: I beg you may oblige me with Answers to the following Questions for the Life of your late excellent Master, which you will be pleased to write under each question…

1. Where was you born? When did you come to England? How was you introduced to Dr. Johnson? At what age did you become his servant? Was you then free?

2. How long was you at sea? In what year did he send you to school in the country? How long did you continue there? Under whose care was you? What were you taught?

[The remaining six questions relate solely to Johnson, his wife and associates.]

Francis’s answers are given in Boswell’s own handwriting, but scholars assume this is because Francis gave him the answers in person (Boswell described the information later as an “authentick and artless account”). Here are the relevant parts about Frank:

Born in Jamaica. Came to England with Colonel Bathurst father of Dr. Bathurst in 1750. Was seven or eight year old. His Master and he went and lived with Dr. Bathurst. He was then sent to the Rev. Mr. Jackson’s school at Barton in Yorkshire. Was there between two and three years. Col. Bathurst made him free in his Will. Then he came up from School was with Dr. Bathurst a short time and then went to Dr. Johnson in Gough square as his servant. But the Dr. first put him to board at Mrs. Coxeter’s that he might go to Blackfriars school. He went one day only for he caught the small pox. After being in the Dr.’s service he went to Mr. Desmoulins writing school.

He lived with Dr. Johnson from 1752 to about 1757—when upon some difference he left him and served a Mr. Farren Apothecary in Cheapside for about two years during which he called some times on his Master and was well received and was to return to him. But having an inclination to go to sea, he went accordingly and continued till the end of 1760… having been discharged thro’ Dr. Johnson’s application, without any wish of his own. Found the Dr. in the Temple and returned to his service.

Johnson was clearly distressed when Francis had run away to sea in 1758 (Johnson says he was “disgusted with the house” for some reason) and wrote to the Admiralty to secure his release. Francis suffered from poor health, too – the novelist Tobias Smollett described him as “a sickly lad of delicate frame, and particularly subject too a malady in his throat”.

Various letters written by Francis have survived. Some are merely administrative; others provide Boswell with research assistance, and Francis was clearly grateful for Boswell’s support, particularly against Hawkins.2 For example, in July 1787 Frank wrote:

Sir: I had the unspeakable Satisfaction of receiving your Letter on Saturday last… and agreeable to your request with a heart full of Joy and gratitude I took Pen in hand to inform you that I am happy to find there is still remaining a friend who has the memory of my late good Master at heart… as I am myself incapable to undertake such a task.

The same letter describes Johnson as “the best of beings” and mentions that Francis is “at present very poorly”.

In 1788, he began to be beset by money troubles – despite Johnson’s bequest, he had had to sell some of the doctor’s effects. In April he wrote to Boswell:

My disorder together with that of three of my Children lately having had the Small pox, has been very expensive to me, so that I am at present rather distressed, and find some difficulty to discharge my Rent for this year; for which reason I shall ever acknowledge as a particular favour if you would advance me Ten pound (which I will repay as I can turn myself about) to release me from my present uneasy situation.

Two years later, things were getting worse. September 1790:

Honoured Sir: It is with much Concern, and Feeling, I pen these Lines, which I hope you will consider and pardon the Liberty I have taken.

I wish I never had come to reside at this Place, but being persuaded by my late poor dear worthy Master, to whom I was, and ought, in duty bound, to oblige, was the occasion. Some time ago, I was extremely ill for a considerable time, which of course incurred a long Doctor’s Bill… I have also been at a great Expense in the care an[d] Education of my Children, as it is my wish, upon my Master’s Account to see them Scholars…

… if you would therefore be pleased to advance me £20 I will repay you honestly, by Eight Guineas on every my Quarterly days, with Interest… and this will be the means of Extricating myself from my present difficulties and put me straight into the world once again, and put my almost broken heart at rest…

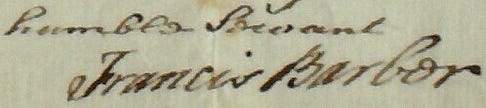

You will excuse me Writing in my own hand as my Eyes are not so good as they were some time back. I remain Sir, Your distressed and most obedient humble Servant,

Francis Barber

Francis notes that his money worries had “not been through my Extravagancy” – though he did later admit to “imprudence”, as we’ll see next. Who can cast the first stone (Hawkins certainly did)?

In 1793, we get another glimpse of Francis, in the words of an unnamed reporter for The Gentleman’s Magazine, who stops off in Lichfield specifically to meet him:

Francis is about 48, low of stature, marked with the small pox, has lost his teeth; appears aged and infirm; clean and neat, but his cloaths the worse for wear; a green coat; his late master’s cloaths all worn out. He spends his time in fishing, cultivating a few potatoes, and a little reading. He laments that he has lost the countenance and table of Miss S [this is the Lichfield poet Anna Seward], Mr. —, and many other respectable good friends, through his own imprudence and low connexions. He was the companion of Johnson; for, as master, he required very small attention: Francis brought and took away his plate at table, and purchased the provisions for the same. But if Francis offered to buckle the shoe, &c., “No, Francis, time enough yet! When I can do it no longer, then you may.”

He was his companion in the evening, when his domesticks made a circle round the fire, where the Doctor chatted and dictated. “Why do not you ask me questions?” the Doctor said to Francis. “But I never could take the same liberty with my master as with another person.” …

Mr. Barber appears modest and humble… [he] is oppressed with a troublesome disorder. I had to regret that my short stay would not admit longer conversation.

Six years later, in 1799, Francis gain needed money and was interviewed for a parish poor relief examination. The examiner’s confirms various details of his life, and we learn “he hath now resident with him in Burntwood aforesaid his wife named Elizabeth and three children Elizabeth aged about fifteen years Samuel aged about thirteen years and Ann aged about ten years”. Francis died in 1801, and his descendants live in Staffordshire to this day.

Here’s Byron’s servant meanwhile, on the poet’s death 200 years ago last week:

And a past encounter with Johnson:

Johnsonian Gleanings II (online here; with apologies for the terminology) and The Fortunes of Francis Barber respectively.

Letters mostly sourced from Waingrow M (ed). The correspondence and other papers of James Boswell relating to the making of the ‘Life of Johnson’. (Edinburgh/Yale 2001).