Merely corporeal, 1775

'The merriest people in the world'?

Two weeks ago we met Janet Schaw, a well-heeled Scotswoman accompanying her brother Alexander to the Caribbean in 1774, where he was due to take up a job as a customs officer. Janet’s diary is a lively read, and she vividly describes the voyage – especially a fierce storm which damages their ship, the Jamaica Packet – as well as her fellow passengers. Among them, hidden in steerage, were “a company of Emigrants”. Initially she sees them en masse as “disgusting a sight”, but comes to know some of them, and feel sympathy for their plight as “hapless exiles… forced by the hand of oppression from their native land”. Remember those words.

Janet and her fellow passengers arrived in Antigua in December 1774. She is suitably awestruck by the aesthetics of the scene she beholds:

The beauty of the Island rises every moment as we advance towards the bay; the first plantations we observed were very high and rocky, and when we got into the bay, which runs many miles up the Island, it is out of my power to paint the beauty and the Novelty of the scene. We had the Island on both sides of us, yet its beauties were different, the one was hills, dales and groves, and not a tree, plant or shrub I had ever seen before; the ground is vastly uneven, but not very high; the sugar canes cover the hills almost to the top, and bear a resemblance in colour at least to a rich field of green wheat; the hills are skirted by the Palmetto or Cabbage tree, which even from this distance makes a noble appearance. The houses are generally placed in the Valleys between the hills, and all front to the sea. We saw many fine ones… Will you not smile [we don’t know who the ‘you’ she writes to was], if after this description, I add that its principal beauty to me is the resemblance it has to Scotland…

With her painterly eye, she goes on to describe the local fort, more sugar plantations and the soldiers strolling through the orange trees and myrtles near the barracks. She soon falls in with “a whole company of Scotch people, our language, our manners, our circle of friends and connections, all the same… we were intimates in a moment”.

Soon she has settled at a plantation called ‘The Eleanora’, owned by a Dr Charles Dunbar:

My bed-chamber, to render it more airy, has a door which opens into a parterre of flowers, that glow with colours, which only the western sun is able to raise into such richness, while every breeze is fragrant with perfumes that mock the poor imitations to be produced by art. This parterre is surrounded by a hedge of Pomegranate, which is now loaded both with fruit and blossom…

She comments that “it is almost impossible to conceive so much beauty and riches under the eye in one moment”. All very nice (apart from the mosquitoes going for her brother). So what are we missing here?

I’m sure you can guess what I’m alluding to. In Professor Elizabeth A. Bohls’ words, a “visual feature of Schaw's aestheticized plantation is the elision of labor”.1 Janet Schaw celebrates how “nature holds out her lap, filled with every thing that is in her power to bestow” – but that’s not quite how it works, is it? In other words, who is making all this comfort and wealth possible? The answer, of course, is slaves.

In the mid-1770s, there were an estimated 37,500 black slaves on Antigua alone,2 thanks to the infamous Atlantic ‘triangular trade’ where Europeans took goods to Africa, slaves to the Caribbean, and brought back sugar and tobacco, forming the powerhouse of empire.

So where are the black people in Janet’s view?

On arrival, she briefly observes “what I took for monkeys were negro children, naked as they were born”. Some while after her arrival, she goes to church, where “a great number of Negroes… went thro’ the Service with seriousness and devotion”. She soon meets Colonel Samuel Martin, whom she describes as the “loved and revered father of Antigua” – he was born on Antigua in 1694, to a long-established family of planters. Janet tells us:

This is one of the oldest families on the Island, has for many generations enjoyed great power and riches, of which they have made the best use, living on their Estates, which are cultivated to the height by a large troop of healthy Negroes, who cheerfully perform the labour imposed on them by a kind and beneficent Master, not a harsh and unreasonable Tyrant. Well fed, well supported, they appear the subjects of a good prince, not the slaves of a planter.

Martin has freed his own staff from slavery in what Bohls drily calls “benevolent paternalism”. Or perhaps he learned a lesson from his father – Major Samuel Martin, who was murdered by his slaves after he forced them to work on Christmas Day in 1701.

Our current Samuel Martin wrote an Essay upon Plantership (1754) which focuses on particular on soil fertility. He plants yams, plantains and potatoes to “fructify the soil” – though according to Anna Foy of the University of Alabama, what he actually meant was feeding these to the slaves and then using their ‘humanure’ to fertilise his sugar crops.3

But back to Janet. Here she is on the day after Christmas 1774, so much more benign than that long-ago one 73 years earlier, again painting a scene:

We met the Negroes in joyful troops on the way to town with their Merchandize. It was one of the most beautiful sights I ever saw. They were universally clad in white Muslin: the men in loose drawers and waistcoats, the women in jackets and petticoats; the men wore black caps, the women had handkerchiefs of gauze or silk, which they wore in the fashion of turbans. Both men and women carried neat white wicker-baskets on their heads, which they ballanced as our Milk maids do their pails. These contained the various articles for Market, in one a little kid raised its head from amongst flowers of every hue, which were thrown over to guard it from the heat; here a lamb, there a Turkey or a pig, all covered up in the same elegant manner, While others had their baskets filled with fruit, pine-apples reared over each other; Grapes dangling over the loaded basket; oranges, Shaddacks, water lemons, pomegranates, granadillas, with twenty others, whose names I forget. They marched in a sort of regular order, and gave the agreeable idea of a set of devotees going to sacrifice to their Indian Gods, while the sacrifice offered to the Christian God is, at this season of all others the most proper, and I may say boldly, the most agreeable, for it is a mercy to the creatures of the God of mercy. At this season the crack of the inhuman whip must not be heard, and for some days, it is an universal Jubilee; nothing but joy and pleasantry to be seen or heard, while every Negro infant can tell you, that he owes his happiness to the good Buccara God [white men's God], that he be no hard master, but loves a good black man as well as a Buccara man, and that Master will die bad death, if he hurt poor Negro in his good day. It is necessary however to keep a look out during this season of unbounded freedom; and every man on the Island is in arms and patrols go all round the different plantations as well as keep guard in the town. They are an excellent disciplined Militia and make a very military appearance.

Riiight.

A few weeks later, Janet has left Antigua and visit St Kitts, where she has a plantation tour, and the “inhuman whip” is rather more visible, but somehow Janet says it’s all just fine.

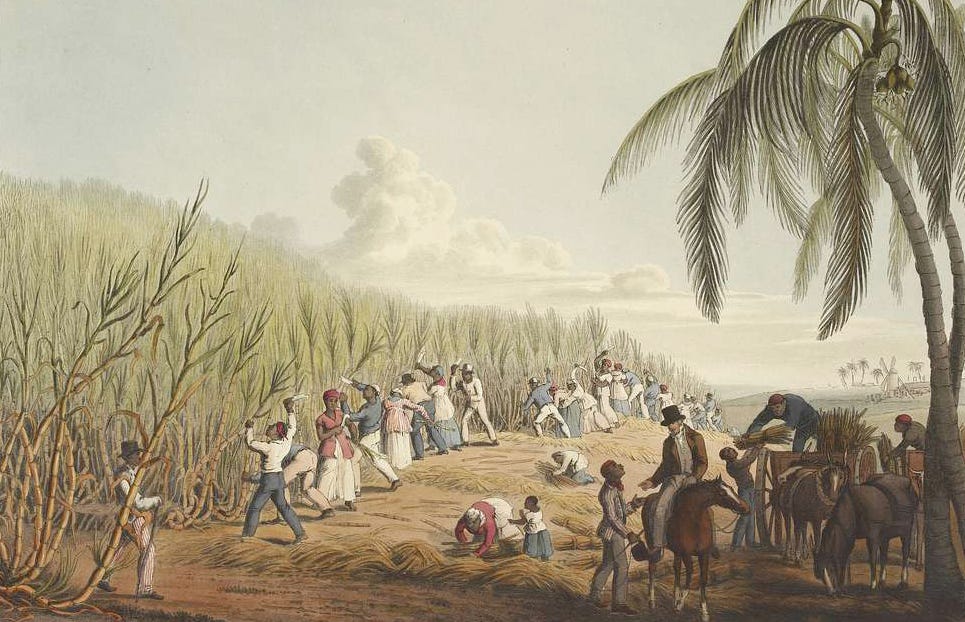

The Negroes who are all in troops are sorted so as to match each other in size and strength. Every ten Negroes have a driver, who walks behind them, holding in his hand a short whip and a long one. You will too easily guess the use of these weapons; a circumstance of all others the most horrid. They are naked, male and female, down to the girdle, and you constantly observe where the application has been made. But however dreadful this must appear to a humane European, I will do the creoles [the descendants of white settlers] the justice to say, they would be as averse to it as we are, could it be avoided, which has often been tried to no purpose. When one comes to be better acquainted with the nature of the Negroes, the horror of it must wear off. It is the suffering of the human mind that constitutes the greatest misery of punishment, but with them it is merely corporeal. As to the brutes it inflicts no wound on their mind, whose Natures seem made to bear it, and whose sufferings are not attended with shame or pain beyond the present moment. When they are regularly Ranged, each has a little basket, which he carries up the hill filled with the manure and returns with a load of canes to the Mill. They go up at a trot, and return at a gallop, and did you not know the cruel necessity of this alertness, you would believe them the merriest people in the world.

Yes, of course Janet was a creature of her time and culture. But her blithe and ‘reasonable’ tone here offers a brutality of a different kind. It would be another six decades before slavery technically ended on Antigua – and a full century after that for their descendants to be allowed a trade union. “It inflicts no wound on their mind”?

Elizabeth A. Bohls (1994), ‘The Aesthetics of Colonialism: Janet Schaw in the West Indies, 1774–1775’, Eighteenth-Century Studies, 27(3)

Anna M. Foy (2016), ‘The Convention of Georgic Circumlocution and the Proper Use of Human Dung in Samuel Martin’s “Essay upon Plantership”’, Eighteenth-Century Studies, 49(34)

Wow, thank you for sharing this. It’s shocking to read contemporary accounts like this. Important to do but shocking every time.