Fevered state, 1808

Wise advice from Mr President

Well, it’s been a week.

I had started to write a piece set during the First World War, but then by chance through a work project I came upon the letter I share with you this week. It’s by a former US president, and it felt very apt. (So I’ll come back to WW1 next time.)

The letter in question is by the Founding Father and third president Thomas Jefferson (1743–1826),1 and it was written in the last few months of his presidency (which ran from 1801 to 1809). I’m not going to dwell for long on his life story, but he grew up in the slave-owning planter colony of Virginia, which he governed during the American Revolutionary War, then rising rapidly through national government. While we must acknowledge he was a slave owner, he was known for his philosophical turn of mind, religious tolerance and support for democracy and free speech. He was interested in farming, architecture and the work of Isaac Newton.

The recipient of the letter I’ll extract from below was his beloved grandson Thomas Jefferson Randolph (1792–1875), only 16 at the time and therefore firmly in the spotlight for some grandfatherly advice – at the time he was studying natural sciences in Philadelphia under the supervision of the same illustrious grandpa.

The two were in regular correspondence2 – back in 1802, the then nine-year-old TJR had written affectionately (and somewhat breathlessly):

My Dear Grand Papa

I hope you are well, it gives me great pleasure to be able to write to you I have been through my latin grammar twice and mamma thinks that I improved in my reading. I am not going to school now but cousin Beverly and my self are going to a latin school in the spring adieu my dear Grand Papa I want to see you very much indeed believe me your affectionate Grandson.

Grand Papa fostered his education, sending him a French grammar book a year later, for example, and then when TJR was at Philly, dispensing advice:

As the commencement of your lectures is now approaching, and you will hear two lectures a day, I would recommend to you to set out from the beginning with the rule to commit to writing every evening the substance of the lectures of the day. It will be attended with many advantages. It will oblige you to attend closely to what is delivered to recall it to your memory, to understand, and to digest it in the evening; it will fix it in your memory, and enable you to refresh it at any future time…

I wonder if TJR followed this advice (as someone currently nagging a 15-year-old to do more exam revision, I suspect not).

In the letter below, written on 24th November 1808, Mr President offers some more extensive advice – much of which we might all learn from in the context of politics and social media today. Over to Tom.

Your situation, thrown at such a distance from us, & alone, cannot but give us all great anxieties for you. As much has been secured for you, by your particular position and the acquaintance to which you have been recommended, as could be done towards shielding you from the dangers which surround you. But thrown on a wide world, among entire strangers, without a friend or guardian to advise, so young too and with so little experience of mankind, your dangers are great, & still your safety must rest on yourself. A determination never to do what is wrong, prudence and good humor, will go far towards securing to you the estimation of the world.

When I recollect that at 14 years of age, the whole care & direction of myself was thrown on myself entirely, without a relation or friend qualified to advise or guide me, and recollect the various sorts of bad company with which I associated from time to time, I am astonished I did not turn off with some of them, & become as worthless to society as they were. I had the good fortune to become acquainted very early with some characters of very high standing, and to feel the incessant wish that I could ever become what they were… From the circumstances of my position, I was often thrown into the society of horse racers, card players, fox hunters, scientific & professional men, and of dignified men; and many a time have I asked myself, in the enthusiastic moment of the death of a fox, the victory of a favorite horse, the issue of a question eloquently argued at the bar, or in the great council of the nation, well, which of these kinds of reputation should I prefer? That of a horse jockey? a fox hunter? an orator? or the honest advocate of my country’s rights? Be assured, my dear Jefferson, that these little returns into ourselves, this self-catechising habit, is not trifling nor useless, but leads to the prudent selection & steady pursuit of what is right.

I have mentioned good humor as one of the preservatives of our peace & tranquillity. It is among the most effectual, and its effect is so well imitated and aided, artificially, by politeness, that this also becomes an acquisition of first rate value. In truth, politeness is artificial good humor, it covers the natural want of it, & ends by rendering habitual a substitute nearly equivalent to the real virtue. It is the practice of sacrificing to those whom we meet in society, all the little conveniences & preferences which will gratify them, & deprive us of nothing worth a moment’s consideration; it is the giving a pleasing & flattering turn to our expressions, which will conciliate others, and make them pleased with us as well as themselves. How cheap a price for the good will of another!

When this is in return for a rude thing said by another, it brings him to his senses, it mortifies & corrects him in the most salutary way, and places him at the feet of your good nature, in the eyes of the company.

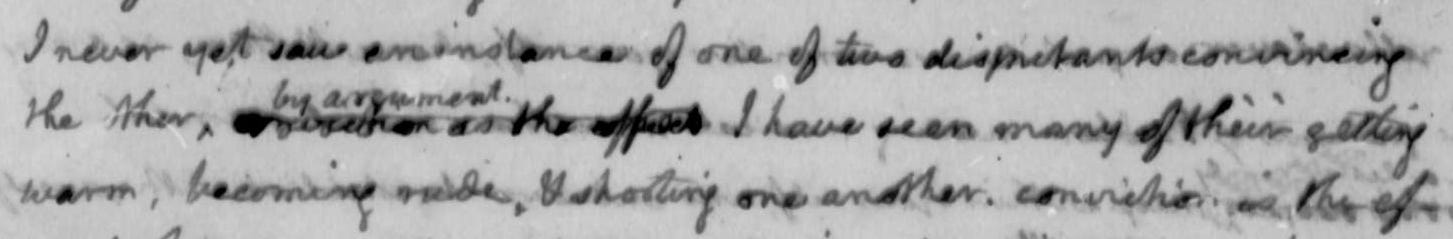

But in stating prudential rules for our government in society, I must not omit the important one of never entering into dispute or argument with another. I never saw an instance of one of two disputants convincing the other by argument. I have seen many, on their getting warm, becoming rude, & shooting one another… It was one of the rules which, above all others, made Doctor [Benjamin] Franklin the most amiable of men in society, “never to contradict anybody.” If he was urged to announce an opinion, he did it rather by asking questions, as if for information, or by suggesting doubts.

When I hear another express an opinion which is not mine, I say to myself, he has a right to his opinion, as I to mine; why should I question it? His error does me no injury, and shall I become a Don Quixote, to bring all men by force of argument to one opinion? If a fact be misstated, it is probable he is gratified by a belief of it, & I have no right to deprive him of the gratification. If he wants information, he will ask it, & then I will give it in measured terms; but if he still believes his own story, & shows a desire to dispute the fact with me, I hear him & say nothing. It is his affair, not mine, if he prefers error.

There are two classes of disputants most frequently to be met with among us. The first is of young students, just entered the threshold of science, with a first view of its outlines, not yet filled up with the details & modifications which a further progress would bring to their knowledge. The other consists of the ill-tempered & rude men in society, who have taken up a passion for politics… From both of those classes of disputants, my dear Jefferson, keep aloof, as you would from the infected subjects of yellow fever or pestilence…

Be a listener only, keep within yourself, and endeavor to establish with yourself the habit of silence, especially on politics. In the fevered state of our country, no good can ever result from any attempt to set one of these fiery zealots to rights, either in fact or principle. They are determined as to the facts they will believe, and the opinions on which they will act. Get by them, therefore, as you would by an angry bull; it is not for a man of sense to dispute the road with such an animal.

TJR would go on to become a politician (and slave owner) in Virginia, and was his grandfather’s executor, later publishing the first collection of Jefferson’s writings. He became a Confederate colonel during the American Civil War, but is not believed to have fought.

The same chap we met briefly last week, counting his paces.