A history of… the pedometer (step tracker)

Some people thought pace counting was a step too far…

I have tracked the number of paces I have walked each day, dutifully in a spreadsheet, for almost a decade now. I realise that this level of step counting is perhaps on the extreme end of things, but many other people at least keep an eye on how many steps they take, be it through a Fitbit, a smartwatch or just their smartphone. Indeed, even though you may be taking no notice of it, your phone is probably counting your paces anyway. I was curious to discover if this obsession with pace counting was a modern affectation, so this week I will be delving into the history of the pedometer.

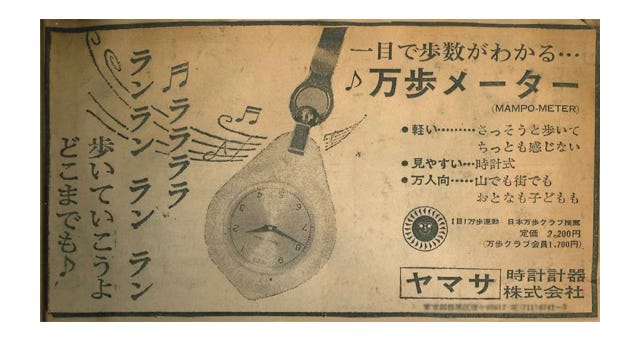

The Tokyo Olympics of 1964 had a huge impact on modern step counting: in the run-up to the games, leading doctor Iwao Ohya was concerned about the levels of inactivity in Japan and decided to do something about it. He decided that the solution was for everyone in the country to walk 10,000 paces a day – a figure that you will doubtless be familiar with as a fitness goal in the 21st century. Interestingly there was no science behind the selection of this number; it simply seemed like a significant but achievable goal and was a nice round number! He shared this idea with engineer Juri Kato, who, after a couple of years’ work, produced the Manpo-kei — the ten-thousand step-metre – a mechanical pedometer. The product launched in 1965 and became hugely popular in Japan, to the extent that the ‘10,000-pace Walking Association’ was formed and soon had branches across the country.

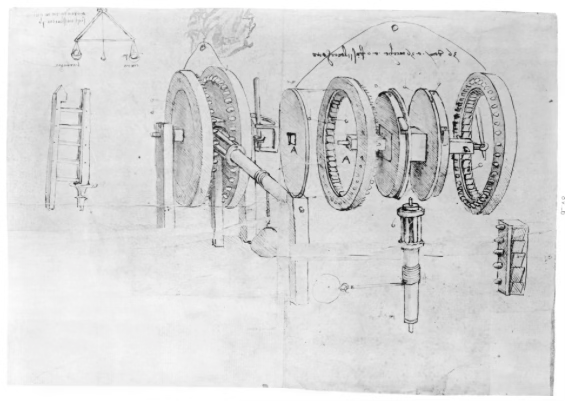

The history of the pedometer is, however, hundreds of years older than this. None other than Leonardo da Vinci left designs for a pedometer in his notebooks (it is unclear whether or not, as with many of his designs, one was actually made). Leonardo’s design used a series of cogs to track the motion of the leg to track paces, and he envisaged this as primarily a military tool, to track distances covered and to lay out encampments.

By the late 16th century pedometers had been made and were in wide usage, both for similar practical purposes, such as measuring farmland, but also simply for counting the number of paces a person walked for the sake of it.

One fan of step counting was Thomas Jefferson, who had a device specially made for him by a Parisian watchmaker. We would probably think its design somewhat cumbersome today – worn in a vest pocket, with a piece of string running from a protruding lever down to a strap that was worn below the knee. Each step would yank the lever down and thus be recorded. Jefferson made good use of it despite this, measuring the distances across Paris and calculating that it took him 2,066.5 paces to cover an English mile at a leisurely pace, and 1,735 when walking briskly. He even sent one of his pedometers to James Madison (along with a page of instructions), though I haven’t been able to establish if Madison used it in earnest.

It was in Britain in the late 18th and early 19th century that the real fad for pace counting kicked off in a manner that is surprisingly similar to today. The rationale then, as now, was that walking was beneficial to health and should be promoted. A particularly eloquent proponent of this view was one R. Gout1 of Ramsgate, writing in the Medical Observer in 1806:

Gentlemen

Exercise forms a necessary appendage to human existence, without which man cannot live, nor health be procured. The most of all others, walking is the most useful and healthy exercise. The more we examine the human constitution, the more the powers of man seem fitted for action; indolence and inactivity are with him the certain source of disease; and temperance and exercise are his surest guardians of health. The general effects of exercise are to increase the strength of the body, by preserving the vigour of circulation; and thus expediting all the secretions and excretions: by which the vital stream is preserved in a pure and healthy state, and all obstructions prevented, or done away. Exercise, though thus attended with the best consequences, should yet be kept within due bounds; and those proportioned to the habits of life, and the constitution of the patient. Repletion, or fulness of habit, is evidently an enemy to it, in a great degree; violent exertion, quickly applied, is mostly to be guarded against, and a regular equable manner of applying it should be used; and with similar precaution after it, exposure to cold should be equally be avoided.

But what form of exercise should be taken? Gout continues:

The first kind of exercise that claims to be noticed, is walking; and perhaps it is, of all others, the most useful and healthy; both body and mind are enlivened by it; and it is highly serviceable, when carried to an extreme, in many nervous diseases. The most proper situation for walking is the country, in dry and serene weather, and the situation of the latter should be particularly studied in the use of this exercise, to give it proper effect: even in the country, damp, marshy ground, is to be avoided; and walking here will have more effect on one accustomed to the town, than on others not confined to this situation. But in case of invalids, and those of a delicate constitution, this exercise, however must be regulated both in its time and duration. Over exertion is here to be avoided, and it should be conducted in that agreeable manner that will give strength without fatigue, and excite a flow of spirits without exhaustion. To do this, a certain regular pace should be employed, and in order to attain it, or get into the habit of using a pace suited to what the strength of each individual can bear, measuring the time taken up is the best and surest rule.

This isn’t simply a public service announcement for the good of humanity by Gout – he has some skin in the game:

I have lately invented a watch for measuring the time2 in walking, which I would recommend to invalids; and as your valuable work is engaged in pointing out what is useful for mankind, I have taken the liberty of sending you a description of it, for the information of your readers.

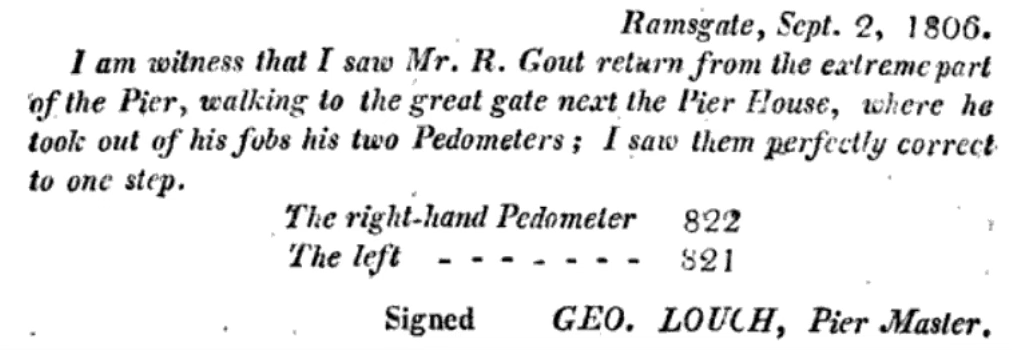

Gout was sufficiently confident in the quality of his product that he arranged a public demonstration of it:

Ramsgate, Sept. 1, 1806.

R. GOUT most respectfully begs leave to acquaint the curious in walking, that he proposes walking to-morrow morning, Sept. 2, at 11 o’clock precisely, from the great gate of Ramsgate Pier to the extreme part, with two of his Pedometrical Watches, one in the right, and one in the left-side pocket, when he will prove to Gentlemen the superior accuracy of his Pedometers, as they must both agree in number of steps at the end of the walk.

R. Gout is induced to make this public, not only because the common Pedometer is generally known to be imperfect, but to shew that he does not wish to impose an instrument on the Public, for the accuracy of which he cannot vouch.

N. B. The number of steps will be from 820 to 830.

This demonstration proved to be a success!

He went on to carry out another demonstration:

These military men were particularly impressed with his invention:

The superiority of Gout’s Pedometer is its exactness, as also to shew the time the curious and easy way to set the hands for counting, which prevents gentlemen the trouble of calculation. And the lever beating the outward lining of the fob, does not render it unpleasant to the wearer, and answers the purposes of a chain.

Much as today, not everyone was a fan of step counting, the view being that it was at best pointless and at worst took the joy away from a good, simple walk. One such person was Christopher North,3 whose Recreations were published in 1867:

But what think you, gentle reader, of walking with a Pedometer? A Pedometer is an instrument cunningly devised to tell you how far and how fast you walk, and is, quoth the Doctor, a “perambulator in miniature.” The box containing the wheels is made of the size of a watch-case, and goes into the breeches pocket, and by means of a string and hook, fastened at the waistband or at the knee, the number of steps a man takes, in his regular paces, are registered from the action of the spring upon the internal wheel-work at every step, to the amount of 30,000. It is necessary, to ascertain the distance walked, that the average length of one pace be precisely known, and that multiplied by the number of steps registered on the dial-plate.

All this is very ingenious; and we know one tolerable pedestrian who is also a Pedometrist. But no Pedometrician will ever make a fortune in a mountainous island, like Great Britain, where pedestrianism is indigenous to the soil. A good walker is as regular in his going as clock-work. He has his different paces – three, three and a half – four, four and a half-five, five and a half – six miles an hour – toe and heel. A common watch, therefore, is to him, in the absence of milestones, as good as a Pedometer, with this great and indisputable advantage, that a common watch continues to go even after you have yourself stopped, whereas, the moment you sit down on your oil-skin patch, why, your Pedometer (which, indeed, from its name and construction, is not unreasonable) immediately stands still. Neither, we believe, can you accurately note the pulse of a friend in a fever by a Pedometer.

I fear that North would be hugely disappointed by the prevalence of fitness tracking devices and apps in 2024 – it turns out that Pedometrists can make a fortune even in, err, a mountainous island like Great Britain! I would hope that I could persuade him that my love of walking in the countryside, despite being measured, matches his own:

What pleasure on this earth transcends a breakfast after a twelve-mile walk? Or is there in this sublunary scene a delight superior to the gradual, dying-away, dreamy drowsiness that, at the close of a long summer day's journey up hill and down dale, seals up the glimmering eyes with honey-dew, and stretches out, under the loving hands of nourrice Nature, the whole elongated animal economy, steeped in rest divine from the organ of veneration to the point of the great toe, be it on a bed of down, chaff, straw, or heather, in palace, hall, hotel, or hut?

For some people in the 19th century walking was not simply a pastime, it was a job and in my next piece I will explore the frankly terrifying world of Victorian competitive walking…

Given that gout is a condition that affects the feet, and reduces the ability to walk, I do wonder if some kind of reverse nominative determinism was in play here.

He used “time” to mean “paces” in this context.

“Christopher North” was the pseudonym of the Scottish writer John Wilson (1785–1854).