'Like so many rocking chairs', 1858

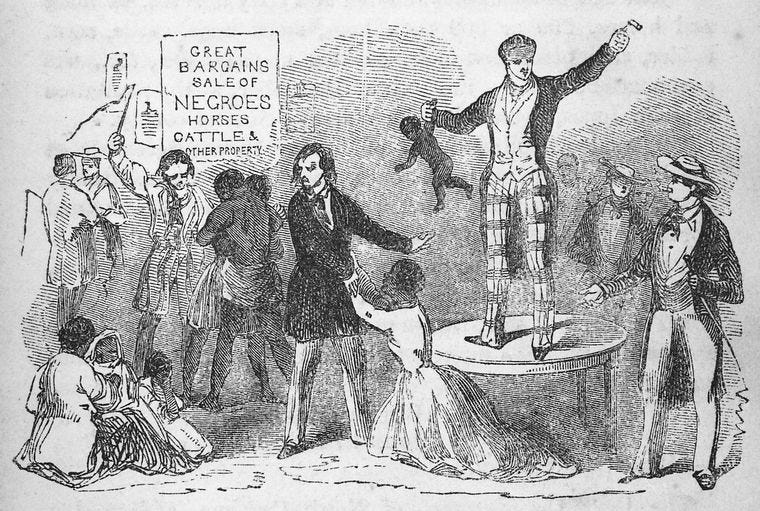

A slave auction in America

Two months ago I wrote here about a famous British author on tour in America (Dickens, of course). This time I give you a British artist doing the same, a decade earlier, but with a very different flavour – and this week’s extract from her diary is potentially distressing. It’s about the subject of slavery, and of course we can’t just overlook the painful aspects of history.

Our writer was born Barbara Leigh Smith in Sussex in southern England in 1827. Her mother Anne Longden was a milliner, and her father Benjamin Leigh Smith a radical politician, whose own father William Smith was one of the leading British campaigners for the abolition of slavery. (He was also Florence Nightingale’s grandfather as well as Barbara’s.) This was a well-off, well-connected family, but with strong left-wing political views for the time, and part of the Dissenting religious tradition. Anne and Ben were also controversial for not being married. They sent their children to school with ordinary working families rather than packing them off to boarding school, and they believed in equality of opportunities.

Barbara herself grew up to become a prominent and pioneering advocate of women’s rights, and founded the campaigning English Woman’s Journal. She was closely connected to other leading feminists, and in the 1860s became co-founder of Girton College, Cambridge University’s first college to accept women. She was also a talented artist, studying under the pre-Raphaelite pioneer William Holman Hunt, and that was her avowed career. In 1857 she had married a French doctor, Eugène Bodichon, and she took his surname, but this was certainly on her terms: in the same year a law giving women access to divorce courts which she had been a notable campaigner for passed, and the couple lived separate lives as much as they wanted to, while also choosing to be together.

In the same year as their marriage, as a sort-of honeymoon, they decided to travel to America, partly to experience first hand its society and the realities of slavery – and remember this was a few years before the American Civil War. “I want to see what sort of world this God’s world is,” wrote Barbara. Some passages of the journal she kept were later published in the Englishwoman’s Journal, but the first full edition only came out in 1972.1

The editor of that edition, Joseph Reed, describes her as a “prickly personality”, but a very observant one: “She sees, perhaps better than any of her fellow citizens except Dickens, the United States at the time of a critical pause.” Campaigning against slavery there had begun a whole century beforehand, and by now emancipation was a much-discussed issue – by 1858 there were in fact 17 free states and 15 slave ones, so a turning point had been reached. But of course there were still many people under slavery, particularly to support the cotton plantations of the South, and it is estimated that in 1860 – the year Abraham Lincoln ran for President campaigning against this “monstrous injustice” – there were four million slaves in the US.

Many of those slaves were bought and sold like livestock, at dedicated slave auctions. In cities where these auctions were banned in public, they were still held in private. One of the major markets was in New Orleans, with slaves brought there by sea and then shipped to the plantations up the Mississippi River.

And it was on that river that Barbara’s journal begins, on the steamer Baltic on 6th December 1857. For someone who was vigorously against slavery, she nonetheless does not write all that sympathetically at times – on the first page she describes a woman on that steamer as “very hideous, very black, and looks very low in the human scale, yet she has the strongest desire for liberty”. There is certainly no call to idealise this “prickly” narrator, who was still subject to the prejudices of her time. But her role as an eyewitness is still valuable. She meets and talks to slaves, and has a journalist’s instinct to hear people’s stories.

On 26th December she records visiting a slave auction in New Orleans, where she feigns commercial interest and listens to the auctioneer lie about the slaves’ rights. On Saturday 13th February 1858, she attended another one, and it is there we pick up her account…

As all my paintings are finished and my easel packed up I seem to have unlimited hours in the day, so I went to a Slave Auction. I went alone (a quarter of an hour before the time) and asked the auctioneer to allow me to see everything. He was very smiling and polite, took me upstairs, showed me all the articles for sale – about thirty women and twenty men, twelve or fourteen babies. He took me round and told me what they could do: ‘She can cook and iron, has worked also in the fields.’ etc., ‘This one a No. 1 cook and ironer –,’ etc. He introduced me to the owner who wanted to sell them (being in debt) and he did not tell the owner what I had told him (that I was English and only came from curiosity), so the owner took great deal of pains to make me admire a dull-looking mulatress and said she was an excellent servant and could just suit me. At twelve we all descended into a dirty hall adjoining the street big enough to hold a thousand people. There were three sales going on at the same time, and the room was crowded with rough-looking men, smoking and spitting, bad-looking set – a mêlée of all nations. I pitied the slaves, for these were slave buyers.

The polite auctioneer had a steamboat to sell, so I went to listen to another who was selling a lot of women and children. A girl with two little children was on the block: ‘Likely girl, Amy and her two children, good cook, healthy girl, Amy – what! only seven hundred dollars for the three? that is giving ’em away! 720! 730! 735! – 740! why, gentlemen, they are worth a thousand dollars – healthy family, good washer, house servant, etc. $750.’ Just at this time the polite gentleman began in the same way: ‘Finigal Sara, twenty-two years old, has had three children, healthy gal, fully guaranteed – sold for no fault, etc. and six hundred dollars? Why, gentlemen, I can’t give you this likely gal,’ etc. etc. Then a girl with a little baby got up and the same sort of harangue went on until eight hundred dollars, I think, I was bid and a blackguard-looking gentleman came up, opened her mouth, examined her teeth, felt her all over and said she was dear or something to that effect.

I noticed one mulatto girl who looked very sad and embarrassed. She was going to have a child and seemed frightened and wretched. I was very sorry I could not get near to her to speak to her. The others were not sad at all. Perhaps they were glad of a change. Some looked round anxiously at the different bearded faces below them, but there was no great emotion visible.

I changed my place and went round to the corner where the women were standing before they had to mount the auction stage. There were two or three young women with babies, laughing and talking with the gentlemen who were round, in a quiet sad sort of way, not merrily. The negroes laugh very often when they are not merry. Quite in the corner was a little delicate negro woman with a boy as tall as herself. They were called on together, and the polite gentleman said that they were mother and son and their master would not let them be separated on any account. Bids not being good they came on down and I went up to them. The girl said she thought she was twenty-five and her son ten. She came from South Carolina. She had always lived in one family and her boy had been a pet in her master’s house. He sold them for debt. He was sorry but he could not help it, and her young missises cried very much when they parted with her boy. She was religious and always went to church. She was much comforted to hear there were good black churches in this strange country. While we talked two or three men came up and questioned her particularly about her health; she confessed it was not strong. They spoke kindly to her but went about their examination exactly as a farmer would examine a cow. It is evident (as Mrs. P. said this morning) planters in general only consider the slaves as means of gaining money. There is not that consideration for them which they pretend in drawing-room conversations. The slave-owners talk of them as the Patriarchs might have spoken of their families and call it a patriarchal institution always, but it is not so – they do not consider their feelings except in rare instances. They tell you in drawing rooms that marriage is encouraged. – It is a farce to say so, if the father is not considered as a part of a the family in sales. Of course there are exceptions and my experience is very limited. I came away very sick with the noise and the sickening moral and physical atmosphere.

Before went the young man of the house had said, ‘Well, I don’t think there is anything to see – they sell them just like so many rocking chairs. There’s no difference.’ And that is the truest word that can be said about the the affair. When I see how Miss Murray speaks of sales and separations as regretted by the owners and as disagreeable (that is her tone if not her words), I feel inclined to condemn her to attend all the sales held in New Orleans in two months [Amelia Murray, a maid of honour to Queen Victoria, had published Letters from the United States, Cuba and Canada in 1856, and as a reviewer of her book wrote at the time, “she has no sympathy with abolitionism”]. How many that would be one may guess, as three were going on the morning I went down.

An American Diary, 1857–8, edited by J.W.Reed, Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1972.

Fascinating and heartbreaking.