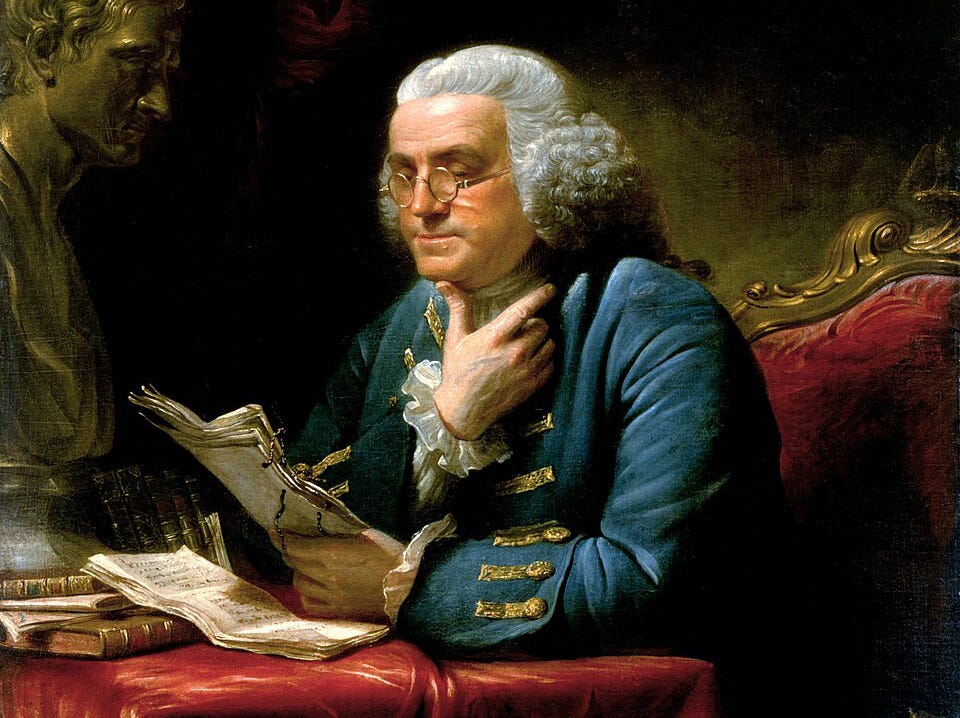

Benjamin airs his views, 1750–81

The misadventures (some real, some not) of a Founding Father

This year I’m hurtling towards my 20th wedding anniversary in October – which also means it’s 20 years since my stag/bachelor party. Being me, it wasn’t sufficient to go to a pub1 or have a curry,2 so of course I persuaded 11 friends to join me in an eccentric re-enactment of the notorious 18th-century Hellfire Club founded by Sir Francis Dashwood (1708–1781), 11th Baron le Despencer.3 And so we found ourselves togged in expensively hired 18th-century costume, embroiled in a complex live action mystery created by Paul, my co-writer of this newsletter, and baffling the innocent residents of West Wycombe as we headed there to visit the caves where Dashwood’s scandalous cronies met.

I mention all this specifically today because one of those licentious cronies (played by my old friend Matthew, a kind supporter of this newsletter) was Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790), who of course helped to draft and later signed the US Declaration of Independence, which was ratified exactly 249 years ago today. Except, er, he wasn’t.

Well, it’s absolutely true that Franklin knew Dashwood. They first corresponded from around 1762, when Dashwood was Chancellor of the Exchequer,4 and their connection was initially one of employer and employee: Dashwood was Britain’s Postmaster General from 1765 until his death, and Franklin was Deputy Postmaster General for the British colonies from 1753 (and later, in 1775–76, Franklin the first ever US Postmaster General).5 In the 1770s, this connection warmed into a good friendship and Franklin was invited to visit Dashwood’s estate at West Wycombe Park (about 30 miles west of London). On 3rd November 1772, for example, Franklin wrote to his son William: “I spent 16 Days at Lord Le Despencer’s most agreably, and return’d in good Health and Spirits.” In another letter to William in August 1773, he was more expansive:

I am in this House as much at my Ease as if it was my own, and the Gardens are a Paradise. But a pleasanter Thing is the kind Countenance, the facetious [here meaning witty] and very Intelligent Conversation of mine Host, who having been for many Years engaged in publick Affairs, seen all Parts of Europe, and kept the best Company in the World is himself the best existing.

But all of this was nearly a decade after the Hellfire Club had fizzled out and middle-aged respectability took over Dashwood’s life. Franklin might have met Dashwood as early as 1757, when he first came to England; he might have been ‘Brother Benjamin’ of the club; and he might even have been a spy for the British government. But he probably wasn’t, and these claims appear to be fabrications by the notoriously dubious ‘historian’ Donald McCormick in the 1950s.6

I say all this because I thought it might be fun to find and share sources describing Poor Richard’s ribald adventures in the caves of Buckinghamshire – but they don’t appear to exist. However, Franklin was a perfectly lively and entertaining character anyway! So this week I’ll share three short, quirky stories about this polymathic pioneer that you might not have come across.

The joys of a bracing air bath

We’ve all heard about the health benefits of cold showers, no doubt, but Franklin preferred a naked encounter with cold air. Here’s part of a letter he wrote to the French physician and scientist Jacques Barbeu-Dubourg (who translated some of Ben’s works into French)7 in July 1768:

I greatly approve the epithet, which you give in your letter of the 8th of June, to the new method of treating the small-pox, which you call the tonic or bracing method. I will take occasion from it, to mention a practice to which I have accustomed myself. You know the cold bath has long been in vogue here as a tonic; but the shock of the cold water has always appeared to me, generally speaking, as too violent: and I have found it much more agreeable to my constitution, to bathe in another element, I mean cold air. With this view I rise early almost every morning, and sit in my chamber, without any clothes whatever, half an hour or an hour, according to the season, either reading or writing. This practice is not in the least painful, but on the contrary, agreeable; and if I return to bed afterwards, before I dress myself, as sometimes happens, I make a supplement to my night’s rest, of one or two hours of the most pleasing sleep that can be imagined. I find no ill consequences whatever resulting from it, and that at least it does not injure my health, if it does not in fact contribute much to its preservation. I shall therefore call it for the future a bracing or tonic bath

From cold air to hot air…

In 1781, the Royal Academy of Brussels issued a call for scientific papers. Franklin got wind (you’ll see why this word is relevant shortly), and impishly decided to mock European pretensions with a satirical paper. He never actually submitted it, but did send it to British philosopher Richard Price, who in turn shared it with gas enthusiast Joseph Priestley (who we’ve met before in, er, passing and will meet again next month!). Here’s an extract:

It is universally well known, that in digesting our common food, there is created or produced in the bowels of human creatures, a great quantity of wind.

That the permitting this air to escape and mix with the atmosphere, is usually offensive to the company, from the fetid smell that accompanies it.

That all well-bred people therefore, to avoid giving such offence, forcibly restrain the efforts of nature to discharge that wind.

That so retain’d contrary to Nature, it not only gives frequently great present pain, but occasions future diseases, such as habitual cholics, ruptures, tympanies, &c. often destructive of the constitution, & sometimes of life itself.

Were it not for the odiously offensive smell accompanying such escapes, polite people would probably be under no more restraint in discharging such wind in company, than they are in spitting, or in blowing their noses.

My Prize Question therefore should be, To discover some drug wholesome & not disagreeable, to be mix’d with our common food, or sauces, that shall render the natural discharges of wind from our bodies, not only inoffensive, but agreeable as perfumes.

That this is not a chimerical project, and altogether impossible, may appear from these considerations. That we already have some knowledge of means capable of varying that smell. He that dines on stale flesh, especially with much addition of onions, shall be able to afford a stink that no company can tolerate; while he that has lived for some time on vegetables only, shall have that breath so pure as to be insensible to the most delicate noses; and if he can manage so as to avoid the report, he may any where give vent to his griefs, unnoticed. But as there are many to whom an entire vegetable diet would be inconvenient, and as a little quick-lime thrown into a jakes [i.e. a toilet] will correct the amazing quantity of fetid air arising from the vast mass of putrid matter contain’d in such places, and render it rather pleasing to the smell, who knows but that a little powder of lime (or some other thing equivalent) taken in our food, or perhaps a glass of limewater drank at dinner, may have the same effect on the air produc’d in and issuing from our bowels? This is worth the experiment. Certain it is also that we have the power of changing by slight means the smell of another discharge, that of our water. A few stems of asparagus eaten, shall give our urine a disagreeable odour; and a pill of turpentine no bigger than a pea, shall bestow on it the pleasing smell of violets. And why should it be thought more impossible in nature, to find means of making a perfume of our wind than of our water?

(He goes on, but you get the idea.)

… and air-fried turkey

And finally, here’s what happened back in Christmas 1750, as Ben related in a letter (probably to his brother John). A very different kind of hellfire…

I have lately made an experiment in electricity that I desire never to repeat. Two nights ago being about to kill a turkey by the shock from two large glass jars containing as much electrical fire as forty common phials, I inadvertently took the whole thro’ my own arms and body, by receiving the fire from the united top wires with one hand, while the other held a chain connected with the outsides of both jars. The company present (whose talking to me, and to one another I suppose occasioned my inattention to what I was about) say that the flash was very great and the crack as loud as a pistol; yet my senses being instantly gone, I neither saw the one nor heard the other; nor did I feel the stroke on my hand, tho’ I afterwards found it raised a round swelling where the fire enter’d as big as half a pistol bullet by which you may judge of the quickness of the electrical fire, which by this instance seems to be greater than that of sound, light and animal sensation. What I can remember of the matter, is, that I was about to try whether the bottles or jars were fully charged, by the strength and length of the stream issuing to my hands as I commonly used to do, and which I might safely eno’ have done if I had not held the chain in the other hand; I then felt what I know not how well to describe; an universal blow thro’out my whole body from head to foot which seem’d within as well as without; after which the first thing I took notice of was a violent quick shaking of my body which gradually remitting, my sense as gradually return’d… that part of my hand and fingers which held the chain was left white as tho’ the blood had been driven out, and remained so 8 or 10 minutes after, feeling like dead flesh, and I had a numbness in my arms and the back of my neck, which continued till the next morning but wore off. Nothing remains now of this shock but a soreness in my breast bone, which feels as if it had been bruised…

…I am ashamed to have been guilty of so notorious a blunder.

Well, lesson learned. Happy Independence Day, if that’s your sort of thing!

And if you’d like to see more glimpses of Founding Fathers, we’ve met two before…

Not that we didn’t.

Not that we didn’t.

It’s important to note that this was not the only Hellfire Club of the era (there were others in both London and Ireland), and indeed that Dashwood never actually called it that. His group had many names, including the Monks of Medmenham and the Order of the Friars of West Wycombe. But all that can be a story for another day.

Despite rumours that he was incapable of adding up more than five figures!

Some of their correspondence survives and is available at the Founders Online website, which is also my source for other letters quoted here.

The whole messy story is told in an excellent series of blog posts at the Boston 1775 website by Massachusetts historian J.L. Bell, starting here. And in fact it’s quite possible that the most exotic collaboration between Dashwood and Franklin was merely producing their own edition of the Book of Common Prayer!