Having written about jokes in my last piece I thought that this week I would explore a different form of entertainment, also usually delivered from a stage: ventriloquism. I was somewhat surprised to learn that this art form (which I usually associate with somewhat terrifying human puppets and rictus grins) is actually incredibly ancient. For much of its history though ventriloquism wasn’t used to entertain people, rather it was used to deceive them…

The earliest recorded ventriloquist was Eurykles of Athens who was a master of the art of εγγαστριμυθία (engastromythia, or ‘belly speaking’). This belly speaking, or gastromancy, was used by Eurykles to convince people that the spirits were speaking through him and that his prophecies should be believed. I mean, it had to be the spirits speaking, because his lips weren’t moving, right? So successful and popular was he that fellow practitioners of this art were known as Euryklides. In Aristophanes’ The Wasps (first performed 422 BCE) we have one of the earliest known mentions of ventriloquism:

At first he kept himself in the background and lent help secretly to other poets, and like the prophetic Genius, who hid himself in the belly of Eurykles, slipped within the spirit of another and whispered to him many a comic hit.

Ventriloquists were also at work in ancient Rome, and it is from Latin that the modern term is derived. They were referred to as ventriloquus – a concatenation of venter (meaning ‘belly’ or stomach’) and loqui (meaning ‘to speak’). While glossolalia (speaking in tongues, also common at the time) I can imagine coming about without deceptive intent – the performer gets caught up in the emotional frenzy of the situation and/or is intoxicated in some manner – ventriloquism is a very different beast. Performing effectively involves not only speaking without moving one’s lips, but also throwing one’s voice to make it seem as though the sound is coming from somewhere other than the perpetrator. To do this convincingly takes a considerable amount of skill and effort, and I find it fascinating to consider that all of the people doing this in a religious setting knew that they were faking it.

Ventriloquists continued to convince the gullible that they were possessed of spiritual powers well into the middle ages, as J. G. Millingen recounts in his 1839 book Curiosities of Medical Experience:

Anthony Vandael, a physician of Harlem, considered ventriloquism as a supernatural power, enabling the voice to proceed “ex ventre inferiore et partibus genitalibus;” and he describes a woman of seventy-three years of age, called Barbara Jacobi, who used to ventriloquise with an imp of the name of Joachim, who would weep most piteously, or fall into roars of laughter, and sometimes danced and sung with remarkable grace and elegance, according to the depressing or exhilarating nature of Mrs. Jacobi’s communications.

The first ventriloquist who made their living through entertainment, rather than deceit, is generally considered to be Louis Brabant, who held the position of ‘King’s Whisperer’ in the court of King Francis the first of France (1494–1547). Though, if one story is to be believed, Brabant was not above using his skills to his own advantage in other ways (taken from an account published in an Australian newspaper in 1826):

Louis Brabant, the valet of Francis I, could not only emit a voice from any distance, or in any direction, but had, also, the art of counterfeiting any voice which he had ever heard. By this extraordinary faculty the following imposition was committed. Brabant had fallen most desperately in love with a young, beautiful, and rich heiress, but was rejected by the parents as an unsuitable match for their daughter.

The father happened to die, Louis waited on the widow, who was totally ignorant of his singular talent,1 pretending to console with her on her loss, when suddenly, in the open day, in her own house, and in the presence of several friends, she hears herself addressed in a voice perfectly resembling that of her deceased husband, and seeing to proceed from above, “Give my daughter in marriage to Louis Brabant! He is a man of great fortunes, and of excellent character. I now suffer the inexpressible torments of purgatory for having refused her to him. If you obey this admonition, I shall soon be delivered from this place of torment. You will, at the same time, provide a worthy husband for your daughter, and procure everlasting repose for the soul of your poor husband.”

The widow could not, for a moment, resist this dreadful summons, which had not the most distant appearance of proceeding from Louis Brabant, whose countenance exhibited no visible change, and whose lips were closed and motionless through the delivery of it.

Unfortunately for Brabant the widow’s bankers took a look at his finances to see if he really was “a man of great fortune” and found that he wasn’t, not even close. Brabant, if nothing else a determined man and a creative thinker, attempted to fix this problem by visiting a banker by the name of Cornu:

During an interval of silence between them, a voice is heard, which to the astonished banker seems that of his deceased father, complaining of his dreadful situation in purgatory, and calling on him instantly to deliver him from thence, by putting into the hands of the worthy Louse Brabant, then with him, a large sum of money for the redemption of Christians in slavery with the Turks; threatening him at the same time with eternal damnation, if he did not likewise take this method to expirate his own sin! It may readily be supposed that Louis Brabant affected a due degree of astonishment on the occasion, and that he further promoted the deception by acknowledging his having devoted himself to the prosecution of the charitable design imputed to him by the ghost.

Further shenanigans follow, with Brabant eventually making it back to Paris in possession of 10,000 crowns of the banker’s fortune. Later, word got back to Cornu of the deception, and he was so embarrassed at being conned that he took to his bed and died soon afterwards.

By the 18th century ventriloquism was well established as a form of entertainment, and one of the first visual representations of it can be seen in William Hogarth’s (typically ribald) 1754 painting An Election Entertainment in which Sir John Parnell MP is making his hand talk.

This hand/handkerchief combination was a forerunner to what is now an integral part of the ventriloquist’s act, the puppet. Well into the 19th century many performers would simply throw their voices so that they would come from objects or locations in the room – there was no mannequin to converse with. A skilled artist, such as the Scot John Rannie, who was active in America in the early 1800s, could achieve considerable impact with this approach causing voices to speak “from the pockets of his audience, or from any object present”. At one performance in New York he claimed:

When the voice proceeded from a Lady’s muff,… the lady was so fully impressed with an idea of reality, that she threw the muff away, with an exclamation of terror and astonishment.

As far back as 1757 it is recorded that the Austrian Baron de Mengen, who dabbled in the art, was using a doll with a moveable jaw in his act, but it wasn’t until later that century that we really see professional usage. James Burne (or Burns) was an Irish performer active around Nottingham in the last decades of the 18th century and he:

…carries in his pocket, an ill-shaped doll, with a broad face, which he exhibits… as giving utterance to his own childish jargon. The gaping croud, who gather round him to see this wooden baby, and hear, as it appears, its speeches, are often deceived; nothing but the movement of the ventriloquist’s lips, which he endeavours to conceal, can lead to the deception.

At around the same time Thomas Garbutt, in addition to the usual voice throwing, was also incorporating a puppet into his act, as this account from Dublin’s Freeman’s Journal in 1798 describes:

A curious occurrence took place, at a tavern, last week between Mr. Garbut [sic], the Ventriloquist, and one of the waiters. The former called for dinner which was served up, and he placed at the table with him his little companion, a puppet, he calls Tommy, with which it would seem he converses, at his exhibition, the oddity of which not a little surprized the waiter. Mr. Garbut having dined, he rang the bell, and the attendant appearing, Tommy, as was imagined, demanded what was to pay.—The waiter at first could not believe his ears; but the question being repeated, Tommy, saying at the same time, he would pay the bill—this so frightened the boy, who could not observe the ventriloquist speaking, he ran down stairs, and swore he would not receive the reckoning in the room he came from, for he was sure the two that were in it in company, were the Devil and some conjurer, and had the Ventriloquist thought proper, he might have come off with dining for nothing, during the consternation the waiter created in the house.

I’d like to end by talking about a man named Richard Potter (1783–1835), who initially worked as an assistant to the earlier mentioned John Rannie. Potter was (not that this was never acknowledged at the time) the son of Sir Charles Frankland, a baronet and tax-collector, and one of his slaves, Dinah. Although Frankland never admitted that Richard was his son, he raised him like one, until at the age of 10 Richard went to sea as a cabin boy for a family, friend, Captain Skinner. Upon arriving in England he saw Rannie perform and decided that the entertainment life was much more appealing than the privations of the maritime, becoming Rannie’s assistant and travelling all around Britain and Europe with him.

He returned to America with Rannie in 1800 to join a travelling circus, and the pair performed together for the next decade. When Rannie retired Potter struck out on his own, performing his first show on the third of November 1811 in the Exchange Coffee House in Boston, with his wife Sally Harris (a Penobscot Indian whom he had married in 1808) as his assistant. This made him both the first professional magician to be born in America and the first known black magician. He used his race to create an air of mystery claiming variously, and dressing accordingly (in what now would probably be considered cultural appropriation!), to be a Native American or a South Asian. He also played upon the ambiguity of his birth and, spelling differences ignored, claimed that he was the illegitimate son of Benjamin Franklin.2

He was astonishingly accomplished and could charge $1 a ticket (at a time when a labourer might make 50 cents a day). Here are some of the tricks he performed (the oven trick sounds amazing!):

Frying Eggs in a Hat.

Breaking Borrowed Watches and Restoring them.

Handling and Swallowing Molten Lead.

Going into an oven with raw meat and remain until the meat was cooked.

Dancing on Eggs without breaking them.

Passing coins through a table.

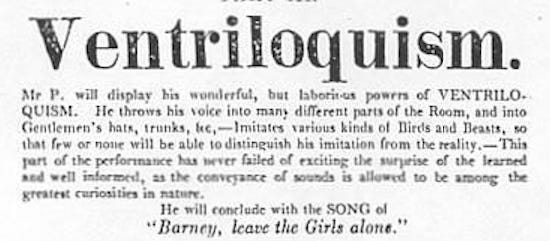

But the highlight of his act was ventriloquism:

He made a fortune, and built a mansion in Andover, New Hampshire, where a township, ‘Potter Place’, was named after him, again almost certainly a first for an African American. As something of an amateur magician myself, I would have loved to have seen him perform, not least because I am intrigued by his ‘Dissertation on Noses’!

In the story, the widow and her family live in Lyon, whereas Brabant lives in Paris, so it does make sense that she doesn’t know about his talent. Though at some point during the courtship one might have expected the parents to ask him what he did for a living!

On the Masonic history website detailing Potter’s life they take the trouble to note: Although Brother Franklin was known to be quite the ladies’ man, he was out of the country at the time of Potter’s conception.