Today in history: September 26

A tyrant at sea, a teenager in wartime, a gangster of legend…

This week’s little stories from contemporary historical sources…

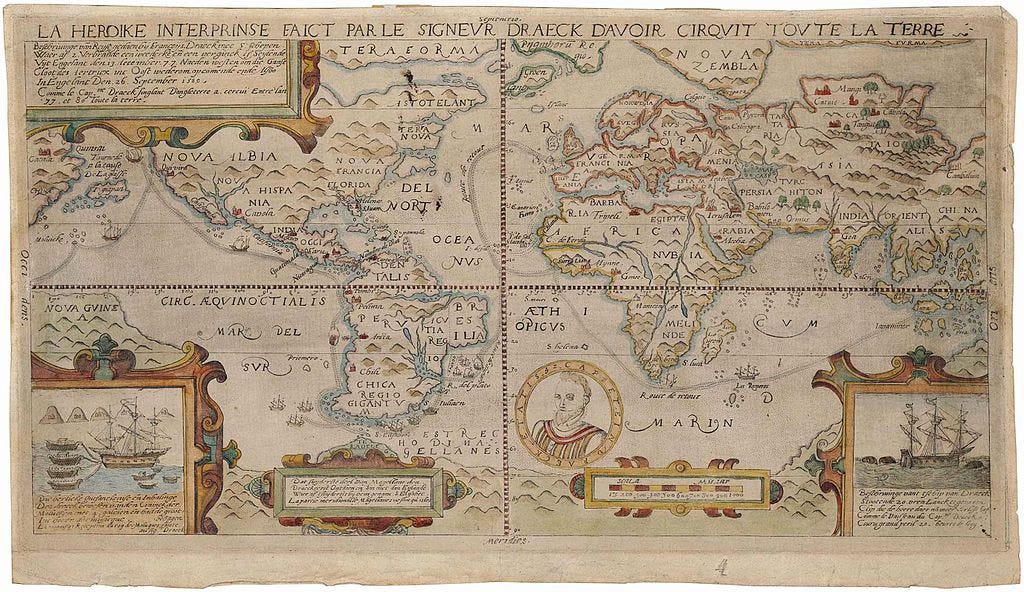

Voyagers return in relief, 1580

[On] the 26 of Sept. (which was Monday in the just and ordinary reckoning of those that had stayed at home in one place or country, but in our computation was the Lord’s day or Sunday) we safely with joyful minds and thankful hearts to God, arrived at Plymouth, the place of our first setting forth, after we had spent 2 years 10 months and some few odd days beside, in seeing the wonders of the Lord in the deep, in discovering so many admirable things, in going through with so many strange adventures, in escaping out of so many dangers, and overcoming so many difficulties in this our encompassing of this nether globe, and passing round about the world, which we have related.

Those are the words of one Francis Fletcher, who was the chaplain who accompanied Francis Drake on his famous circumnavigation of the world (the second such trip in recorded European history).1 Or at least, they’re possibly Fletcher’s words – they were printed in the 1628 book The World Encompassed by Sir Francis Drake which was compiled by the explorer’s nephew – also called Sir Francis Drake – from his uncle’s journal and that of Fletcher.

Only the part of Fletcher’s journal from earlier in the voyage survives unedited – and as he was no great fan of his employer, we might assume the younger Drake has massaged the text. For example, Drake senior had another voyager on the trip, Thomas Doughty, beheaded – a story for another day – which appalled Fletcher, who delivered a sermon to say as much. Another (anonymous) account then tells us…

Drake excommunicated Fletcher… in this manner, viz., he caused him to be made fast by one of the legs with a [shackle?] and a staple knocked fast into the hatches in the forecastle of his ship. He called all the company together, and then put a lock about one of his legs; and Drake, sitting cross-legged on a chest, with a pair of pantoffles [slippers] in his hand, said:

“Francis Fletcher, I do here excommunicate thee out of the Church of God, and from all the benefits and graces thereof; and I denounce thee to the devil and all his angels.”

And then he charged him, upon pain of death, not once to come before the mast; for if he did, he swore he should be hanged. And Drake caused a posy to be written and bound about Fletcher’s arm, with charge that if he took it off he should then be hanged. The posy was: “Francis Fletcher, the falsest knave that liveth.”

Oddly enough, Drake junior’s book mentions neither the execution of Doughty nor this incident with Fletcher. Though after nearly three years at sea, the “joyful minds and thankful hearts” at arriving home seem likely enough – especially given Sir F’s notoriously autocratic style of captaincy!

The clang of arms, 1777

Philadelphia, 1777. A 16-year-old girl called Sally Wister, born into a family that had become Quakers, begins keeping “a sort of journal of the time that may expire”, compiled as letters to her friend Debbie Norris and prompted by political events unfolding around her. We join her on September 26th, writing from North Wales, Pennsylvania, where her family have fled for reasons that will become clear:

We were unusually silent all the morning; no passengers came by the house, except to the Mill, & we don’t place much dependence on Mill news.

About twelve o’clock, cousin Jesse heard that Gen. Howe’s army had moved down towards Philadelphia. Then, my dear, our hopes & fears were engaged for you. However, my advice is, summon up all your resolution, call Fortitude to your aid, and don’t suffer your spirits to sink, my dear; there’s nothing like courage; ’tis what I stand in need of myself, but unfortunately have little of it in my composition.

I was standing in the kitchen about 12, when somebody came to me in a hurry, screaming, “Sally, Sally, here are the light horse!” This was by far the greatest fright I had endured; fear tack’d wings to my feet; I was at the house in a moment; at the porch I stopt, and it really was the light horse.

I ran immediately to the western door, where the family were assembled, anxiously waiting for the event. They rode up to the door and halted, and enquired if we had horses to sell; he was answer’d negatively.

“Have not you, sir,” to my father, “two black horses?”

“Yes, but have no mind to dispose of them.”

My terror had by this time nearly subsided. The officer and men behav’d perfectly civil; the first drank two glasses of wine, rode away, bidding his men follow, which, after adieus in number, they did. The officer was Lieutenant Lindsay, of Bland’s regiment, Lee’s troop. The men, to our great joy, were Americans, and but 4 in all. What made us imagine them British, they wore blue and red, which with us is not common.

It has rained all this afternoon, and to present appearances, will all night. In all probability the English will take possession of the city to-morrow or next day. What a change will it be! May the Almighty take you under His protection, for without His divine aid all human assistance is vain…

Nothing worth relating has occurred this afternoon. Now for trifles. I have set a stocking on the needles, and intend to be mighty industrious. This evening some of our folks heard a very heavy cannon. We supposed it to be fir’d by the English. The report seem’d to come from Philada. We hear the American army will be within five miles of us tonight.

The uncertainty of our position engrosses me quite. Perhaps to be in the midst of war, and ruin, and the clang of arms. But we must hope the best.

In fact, General Howe – Commander-in-Chief of the British Army in America – marched into Philadelphia that same day and occupied the city. But the mission would ultimately fail – Howe would resign the next spring, the War of Independence would rage on for another six years… and we all know who won!

Don’t shoot!, 1933

September 26th 1933, and a 38-year-old gangster from Memphis, Tennessee is holed up in a friend’s house in his home town. He has been hiding from the authorities ever since he had kidnapped oil tycoon Charles F. Urschel at gunpoint in Oklahoma City back in July and demanded a ransom via a friend of Urschel, which read:

Immediately upon receipt of this letter you will proceed to obtain the sum of TWO HUNDRED THOUSAND DOLLARS ($200,000.00)2 in GENUINE USED FEDERAL RESERVE CURRENCY in the denomination of TWENTY DOLLARS ($20.00) Bills.

It will be useless for you to attempt taking notes of SERIAL NUMBERS MAKING UP DUMMY PACKAGE, OR ANYTHING ELSE IN THE LINE OF ATTEMPTED DOUBLE CROSS. BEAR THIS IN MIND, CHARLES F. URSCHEL WILL REMAIN IN OUR CUSTODY UNTIL MONEY HAS BEEN INSPECTED AND EXCHANGED AND FURTHERMORE WILL BE AT THE SCENE OF CONTACT FOR PAY-OFF AND IF THERE SHOULD BE ANY ATTEMPT AT ANY DOUBLE XX IT WILL BE HE THAT SUFFERS THE CONSEQUENCE.

The ransom was paid, Urschel released, and the kidnapper fled into hiding. But now the FBI had caught up with him.

What happened at the raid has gone into American legend, with the gangster – George ‘Machine Gun Kelly’ Barnes – allegedly being unarmed and yelling, “Don’t shoot, G-Men! Don’t shoot, G-Men!”3 But if you’ve spotted one theme across many articles Paul and I have written here… this didn’t happen.

Appropriately enough, the FBI themselves have investigated and found the earliest reference to ‘G-Men’ at all came from “many months later”, when Kelly was reported to have told a journalist, “It was them G’s. Them G’s would have slaughtered me.” This was then transmuted into the legendary line by Washington Star reporter (and friend of J. Edgar Hoover) Rex Collier. And earlier reports said that instead Kelly had said simply, “I’ve been expecting you.”

But in fact the earliest report was compiled by the Feds themselves, only a few days after the capture:

“Agent Rorer saw that Kelly… had proceeded into the front bedroom and was in a corner with his hands raised. He was covered by Sergeant William Raney.”

No grand words recorded. And what seems likely is that the FBI used Collier’s version as propaganda for their successes, and they’ve been dining out on it ever since.4

The first, in the sense of navigating to Asia via the Atlantic and the Pacific, was by Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan between 1519 and 1522. Drake’s purported voyage of discovery meanwhile was probably not intended to be a circumnavigation, given that he was secretly commissioned by Elizabeth I to raid Spanish ports and ships in the Americas.

The equivalent of around $4.5m today.

The story goes that this term, short for ‘government men’, was ever after used to refer to the Feds, though in fact its first known use is five years earlier, referring to any government agents.

Actually, perhaps the most interesting part of the whole story is how the FBI caught Kelly in the first place, which was largely down to the victim: while blindfolded, Urschel paid close attention to the sounds around him and worked out that an airplane passed regularly at 9.45am and 5.45pm, as well as counting footsteps he heard, noting the weather and deliberately leaving fingerprints around the Texas farmhouse where he was held. Nice work, Ursch!

There's something very odd about that piece about Drake, since Elizabeth wasn't born until 1533, and didn't become queen until 1558