Today in history: November 21

A flight, a marvel, a hoax…

This week’s little stories from contemporary historical sources…

Not just hot air, 1783

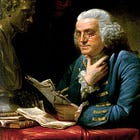

By November 1783, Paris was obsessed with balloons. The Montgolfier brothers had already sent animals aloft from Versailles; now came something unprecedented: a manned free flight over the city. On 21 November 1783, Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier and François Laurent d’Arlandes ascended in a Montgolfier hot air balloon from the gardens of La Muette, watched by crowds and dignitaries. One of the people in that crowd was our old friend Benjamin Franklin, serving as American minister in Paris and living nearby in Passy.

Franklin wrote an eyewitness report to Sir Joseph Banks, president of the Royal Society. In it he describes both the technical workings of the balloon and the sheer strangeness of seeing humans rise into the sky. Explaining how the hot air kept it aloft, he writes:

This Balloon was larger than that which went up from Versailles and carried the Sheep, &c. Its bottom was open, and in the middle of the Opening was fixed a kind of Basket Grate in which Faggots and Sheaves of Straw were burnt. The Air rarified in passing thro’ this Flame rose in the Balloon, swell’d out its sides, and fill’d it.

The Persons who were plac’d in the Gallery made of Wicker, and attached to the Outside near the Bottom, had each of them a Port thro’ which they could pass Sheaves of Straw into the Grate to keep up the Flame, & thereby keep the Balloon full. When it went over our Heads, we could see the Fire which was very considerable… If those in the Gallery see it likely to descend in an improper Place, they can by throwing on more Straw, & renewing the Flame, make it rise again, and the Wind carries it farther…

The Gallery hitched among the top Boughs of those Trees which had been cut and were stiff while the Body of the Balloon lean’d beyond and seemed likely to overset. I was then in great Pain for the Men, thinking them in danger of being thrown out, or burnt for I expected that the Balloon being no longer upright the Flame would have laid hold of the inside that leaned over it. But by means of some Cords that were still attach’d to it, it was soon brought upright again, made to descend, & carried back to its place. It was however much damaged…

They say they had a charming View of Paris & its Environs, the Course of the River, &c but that they were once lost, not knowing what Part they were over, till they saw the Dome of the Invalids, which rectified their Ideas…

There was a vast Concourse of Gentry in the Garden, who had great Pleasure in seeing the Adventurers go off so chearfully, & applauded them by clapping &c. but there was at the same time a good deal of Anxiety for their Safety. Multitudes in Paris saw the Balloon passing; but did not know there were Men with it, it being then so high that they could not see them.1

This voyage is usually regarded as the starting gun for human flight: it proved that people could survive aloft and land safely, and it triggered an immediate balloon craze across Europe. Within weeks, Jacques Charles was flying hydrogen balloons, a competing technology that quickly eclipsed hot air for scientific and long-distance flights. And by the 1790s, France was using balloons for military observation (an idea Franklin mentions later in his letter).

Hot air preserved in wax, 1877

By late 1877, Thomas Edison had already made his name in telegraphy and telephony. Then came something truly uncanny: a device that could record and replay the human voice mechanically. He announced his invention of this ‘talking phonograph’ on November 21 that year.

Soon after, Edison demonstrated it in the offices of Scientific American in New York. The magazine published an anonymous article dated December 22 (but actually released a few days earlier) describing the demonstration and speculating on possible uses – from dictation and letter-writing to preserving famous speeches and even the voices of the dead. Here’s the memorable opening of that piece:

Mr. Thomas A. Edison recently came into this office, placed a little machine on our desk, turned a crank, and the machine inquired as to our health, asked how we liked the phonograph, informed us that it was very well, and bid us a cordial good night. These remarks were not only perfectly audible to ourselves, but to a dozen or more persons gathered around, and they were produced by the aid of no other mechanism than the simple little contrivance explained and illustrated below…

The article continues by explaining how the tinfoil-wrapped cylinder is indented by sound vibrations and then “reads itself” back. The writer then notes:

No matter how familiar a person may be with modern machinery and its wonderful performances, or how clear in his mind the principle underlying this strange device may be, it is impossible to listen to the mechanical speech without his experiencing the idea that his senses are deceiving him.

With this “machinery”, Edison effectively created an entirely new category of technology and, soon, a global recorded music industry. The phonograph also fed back into other inventions: ideas about synchronising sound and image helped shape early motion pictures, while the very notion that voices and music could be replayed at will changed listening habits and even concepts of memory, presence and celebrity.

It was all hot air, 1953

In 1912, various fossil fragments including part of a skull were uncovered in Sussex, England, found by an amateur archaeologist called Charles Dawson. In due course these were announced by the Geological Society as Eoanthropus dawsoni – ‘Piltdown Man’ – and hailed as a crucial ‘missing link’ between apes and humans. For decades, this supposedly ancient English ancestor sat at the centre of human evolution debates.

By mid-20th century, however, new finds in Africa and Asia, plus technological advances, made Piltdown increasingly suspect. On November 21 1953, Joseph Weiner, Kenneth Oakley and Wilfrid Le Gros Clark published ‘The Solution of the Piltdown Problem’ in the Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History), Geology, using fluorine testing, nitrogen content, microscopic analysis and staining studies to show the ‘fossil’ was a modern human skull married to an orangutan jaw, artificially stained and filed. Weiner et al. soberly noted:

From the evidence which we have obtained, it is now clear that the distinguished palaeontologists and archaeologists who took part in the excavations at Piltdown were the victims of a most elaborate and carefully prepared hoax. Let it be said, however, in exoneration of those who have assumed the Piltdown fragments to belong to a single individual, or who, having examined the original specimens, either regarded the mandible and canine as those of a fossil ape or else assumed (tacitly or explicitly) that the problem was not capable of solution on the available evidence, that the faking of the mandible and canine is so extraordinarily skilful, and the perpetration of the hoax appears to have been so entirely unscrupulous and inexplicable, as to find no parallel in the history of palaeontological discovery.

Later that day, London’s Evening News announced: PILTDOWN MAN A HOAX, THEY SAY. And a week or so later, the news was drily reported in Time magazine: “For more than a generation, a shambling creature with a human skull and an apelike jaw was known to schoolchildren, Sunday-supplement readers and serious anthropologists as ‘the first Englishman.’…”

It would be a long time before the perpetrator was identified, with suspects including the philosopher Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, who had helped Dawson with digs, and even Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. But perhaps you can guess who was ultimately named and shamed in 2016, exactly a century after his death: yup, Charles Dawson, who even had form from a host of other minor hoaxes. Occam’s razor wins again.

One of a series of letters compiled by Abbott Lawrence Rotch in Benjamin Franklin and the First Balloons (1907).

Fascinating and diverse collection of stories, as ever. Great ‘hot air’ link!

When it comes to synchronized sound and motion picture, it turns out that the earliest example of synchronized recording was in 1894, which I explain in my post here: https://professortom.substack.com/p/on-synchronized-sound-with-motion However, as I explain in that article, while the recording was synchronized, playback was not.

And it also turns out that the Jazz Singer from 1927 wasn't the first motion picture with synchronized sound. It was the first "feature-length" motion picture that had synchronized dialog.