Today in history: August 15

The original big Mac; a man, a plan, a canal; and the last of a poet…

This week’s little stories from contemporary historical sources…

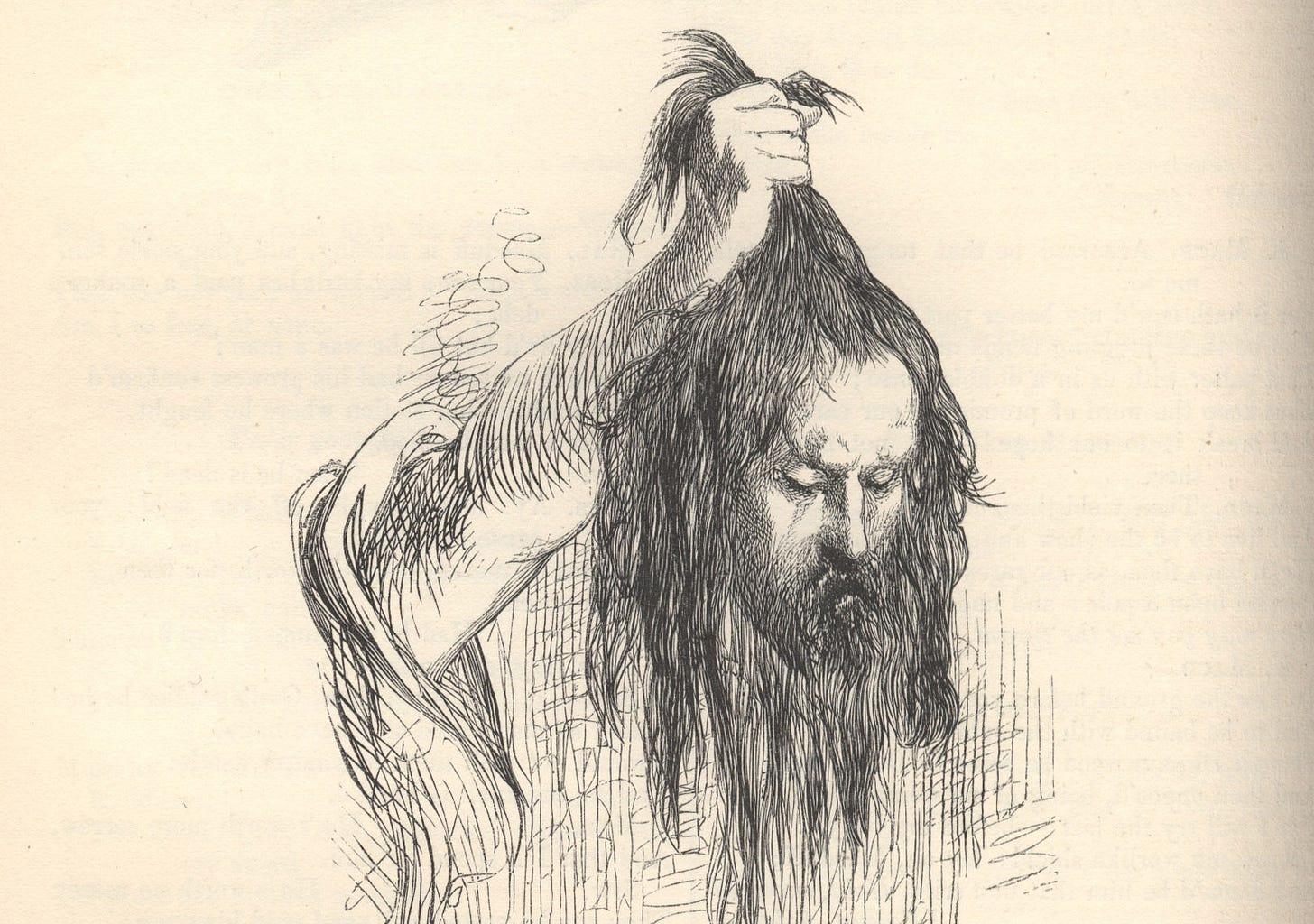

Macbeth loses his head, 1057

I will not yield,

To kiss the ground before young Malcolm’s feet…

…Before my body

I throw my warlike shield: lay on, Macduff;

And damn’d be him that first cries, “Hold, enough!” [Exeunt, fighting.]

Thus Shakespeare gives the last words of Macbeth, and not long after that the flawed tyrant’s head is brought back by his nemesis Macduff. So it goes.

The real Scottish king Macbeth is said to have died on August 15th in the year 1057. It’s pretty tricky to reach as far back in time as the 11th century and find accurate sources – mostly we just have chronicles compiled by monks. Shakespeare borrowed his version of the Macbeth story from the 16th-century chronicler Raphael Holinshed, who was hired by a London printer to finish off an ambitious history of the world – and lived in an era when (like Shakey himself) there was no pressure to credit his sources. Raphael himself borrowed the story of Macbeth from the Scottish historian Hector Boece (aka Boethius, 1465–1536), who was intent on flattering the ancestors of his patron, James IV of Scotland – which meant portraying their enemy Macbeth as the bad guy.

Before Boethius, Andrew of Wyntoun, writing c.1420, gave us the first version of the weird sisters and their prophecy. Earlier still, the 14th-century chronicler John of Fordun introduced the story of Macduff severing Macbeth’s head. But the evidence from the 11th century, such as it is, doesn’t say any of this!

Macbeth was certainly credited with killing his predecessor, King Duncan, but in battle rather than through nocturnal intrigue. He then had a mostly peaceful reign, until being killed himself at the Battle of Lumphanan by Duncan’s son Malcolm III, or forces loyal to him.1

The Chronicle of the Kings of Alba, possibly written in the 11th century, gives us pretty much the longest contemporary account:

Macbeth, Findlaech’s son, reigned for seventeen years. And he was killed in Lumphanan, by Malcolm, Duncan’s son; and was buried in the island of Iona.2

Er, that’s it. Another chronicle says Malcolm “cut him off by a cruel death”. And the Irish chronicler Marianus Scotus gives us the August 15th date – as well as a passing reference to Macbeth visiting Rome and giving money to the poor there. It’s a long stretch from these snippets to the story told by Shakespeare, and clearly many of the elements of the story we think of today are embellishments from medieval folklore!

Hats off to Panama (I), 1519

August 15th is a notable day in the history of Panama for two quite different reasons. First, it’s the date in 1519 when what became Panama City was first founded by the Spanish conquistador Pedro Arias de Ávila (aka Pedrarias, c.1440–1531), who led the biggest Spanish expedition of the era to mainland America. He was known for his bravery on the battlefield, his extravagant lifestyle (one legend also claims he was almost buried alive and carried his coffin with him ever after)… and his cruelty.

Not unlike Macbeth, he had his predecessor as governor of Veragua (which included much of modern Panama), Vasco Núñez de Balboa, executed (another decapitation), and was known for his cruelty. Dávila was already in his 70s when all this was going on.

The settlement he founded – the first permanent European one on this Pacific coast – was based around what is now called Panamá Viejo, now a UNESCO World Heritage site. Sadly the original charter he drew up is lost. The city soon became an important hub for siphoning Incan gold and silver off to Spain – an early document from September that year reports that “the gold recently smelted during the last stopover yielded 104,958 pesos, of which 25,581 fell to His Highness”, so Dávila clearly did well for himself.

Pascal de Andagoya, one of Dávila’s co-founders, wrote a narrative of this conquest era and tells us “The governor divided the land amongst the four hundred citizens who then settled in Panama… Panama was founded in the year 1519, on the day of Nuestra Señora de Agosto”. The name Panama apparently means “place of many fish”.

The Spanish court historian Antonio de Herrera y Tordesillas (1549–c.1625) wrote that Panama is (in a 1725 English translation): “a province where the air is wholesome when it blows off the sea, and bad when it comes from the land. It abounds in gold, as also in deer and fowl.”

And there’s even a little gory story:

At Panama an alligator has been known to take a man off from the stern of a boat, and carry him away to the rocks, where as he was tearing him in pieces, he was kill’d with a musket shot; the man being recover’d as the Monster was biting him off near the groin, was carry’d to the Hospital, where he liv’d long enough to receive the Rites of the Church.

So it goes. Herrera also reported:

…men abhorring the place by reason of its unwholesome situation, being excessive hot and moist, for which reason during the first twenty-eight years after the conquest of Peru, above forty thousand Men were computed to have died there of violent distempers… many thousands of Spaniards have perish’d by reason of the bad air.3

Remarkably, the first idea of a canal across this isthmus was conceived in this era: in 1533, Dávila’s captain Gaspar de Espinosa wrote to Emperor Charles V: podría hacerse acequia del agua del Chagres hasta la Mar del Sur y que se navegase. Son como cuatro leguas de tierra llana – “A canal could be made with water from the [River] Chagres to the South Sea, and it could be navigated. It is about four leagues of flat land.” This then prompted an official survey ordered by Charles in 1534 – though nothing came of it. But read on!

Hats off to Panama II, 1914

The first concerted effort to actually dig a canal here came from French entrepreneur Ferdinand de Lesseps, starting in 1881, but after 18 long years (and the deaths of more than 22,000 people), the project went bankrupt. A few years later, the US rode to the rescue and gave us the canal we know today as an essential global shipping route – and it opened on August 15th 1914, 395 years after the city of Panama was founded (and only two weeks after the First World War had started).4

The first ship to pass through on that day was the SS Ancon, a US cargo steamship. Of course, we have lots more sources for this event.5 Around 200 people were invited as passengers on that first canal crossing between the world’s great oceans, and one of them, John Barrett, director general of the Pan American Union, left us a detailed account. So here is an extract:

…she made the passage from Cristobal to Balboa, from Colon to Panama, from deep water of the Atlantic to deep water of the Pacific, without a hitch, accident, or unpropitious incident of any kind. So quietly did she pursue her way that, except for the plaudits of the multitude who thronged the locks and hills along the route, a strange observer coming suddenly upon the scene would have thought that the canal had always been in operation, and that the Ancon was only doing what thousands of other vessels must have done before her…

…The effect of the tropical climate upon the concrete work of the gigantic locks, while doing them no damage, has given them the color of age. So well did every man perform his duty in the opening and shutting of the massive gates of the locks and in the moving of the electric towing locomotives, commonly called “mules,” that it seemed to expert and layman alike as if they had been sending other Ancons day after day…

The towering gates of the locks swung shut or open with the trueness of the pendulum of the old clock on the stairs… We were indeed astonished but gratified when we saw the Anconclimb the triple flight of locks from the level of the Atlantic Ocean…

…With green hills forming a restful background and with picturesque islands dotting the waters here and there, it was not easy to realize that we were crossing, as it were, a great water bridge between the Atlantic and the Pacific.6

Shelley loses his head, 1822

As a final note, August 15 1822 was the date when the poet Shelley was cremated on the shores of Italy. His friend Edward Trelawny wrote an account with rather too much detail: “the brains literally seethed, bubbled, and boiled as in a cauldron, for a very long time”. (He also noted, “Byron asked me to preserve the skull for him; but remembering that he had formerly used one as a drinking-cup, I was determined Shelley’s should not be so profaned.”)

But we’ve covered the death of Shelley before:

Macbeth’s son Lulach was actually then king for a few months until Malcolm killed him too. One chronicle harshly calls him Lulach fatuus, which is basically “Lulach the dumbass”.

This and other chronicles are listed in Early Sources of Scottish history, A.D. 500 to 1286 by Alan Orr Anderson (1922).

These quotations come from the 1725 English translation by John Stevens, The General History of the Vast Continent and Islands of America.

Technically, the first complete passage was by the SS Cristobal, a cement ship, but that wasn’t glamorous enough for the official opening, and an earlier French vessel had done it in stages during construction.

Though in his comprehensive study The Path Between the Seas, David McCullough (2002) notes slightly disappointedly: “Across Europe and the United States, world war filled the newspapers and everyone’s thoughts. The voyage of the Cristobal, the Ancon’s crossing to the Pacific on August 15, the official declaration that the canal was open to the world, were buried in the back pages. There were editorials hailing the victory of the canal builders, but the great crescendo of popular interest had passed…”

Published in the September 1914 issue of the Pan American Journal. There’s loads more detail that space denies us here but I did rather like this: “Another crowd of admiring spectators welcomed the Ancon at the entrance to Pedro Miguel Lock. Among them were 100 women school teachers from London who had come all the way from England to see this mighty waterway.”