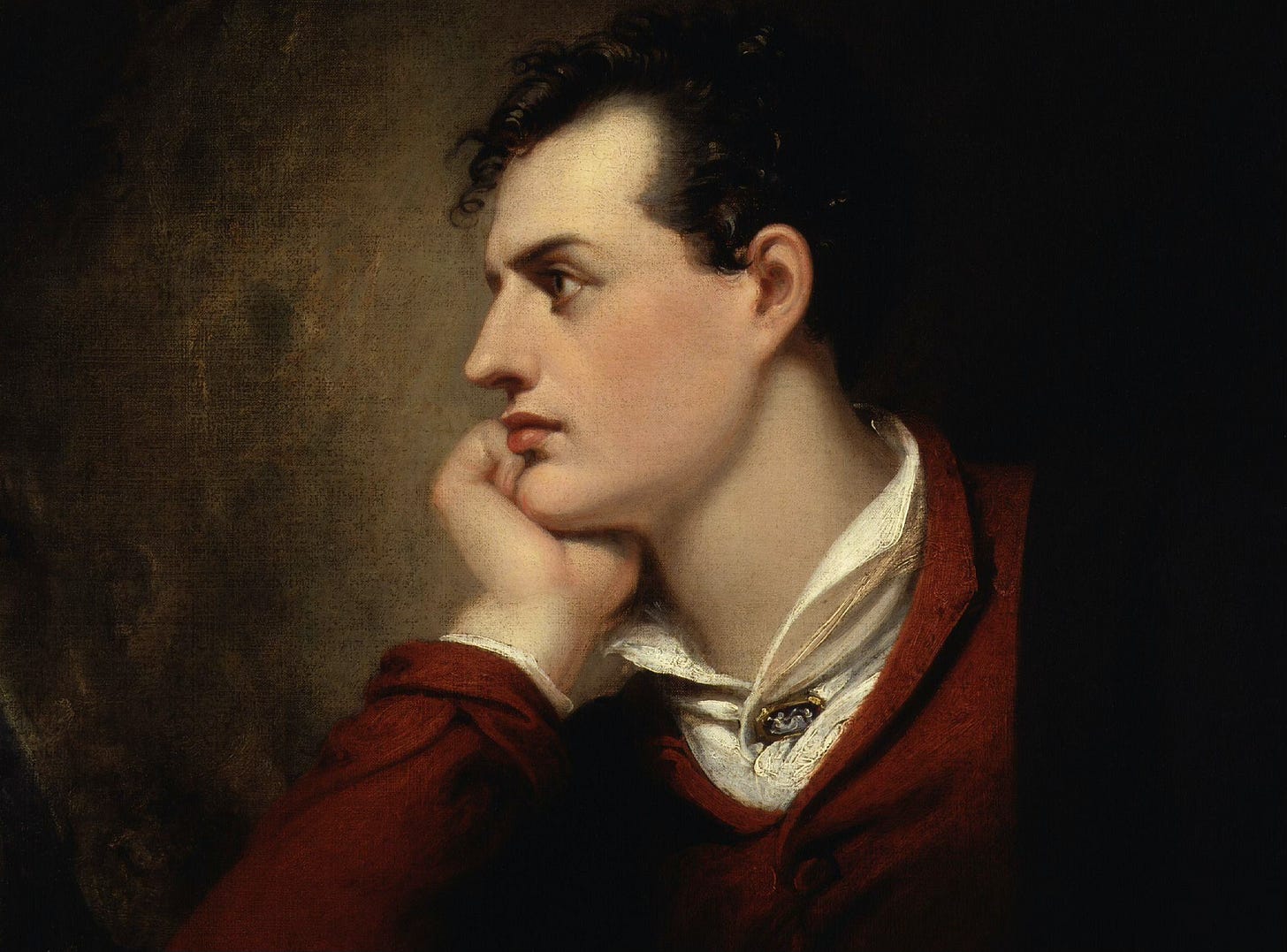

Byron is bored, 1821

Even a pet crow can't help.

“A sudden thought strikes me. Let me begin a journal once more.”

So begins the ‘Ravenna Journal’ of George Gordon, Lord Byron, on 4th January 1821, written in Italy. He goes on to comment that “the last I kept was in Switzerland, in record of a tour in the Bernese Alps, which I made to send my sister in 1816” and that he’d kept another before that, from 1813 to 1814 in London, given to his friend Thomas Moore.

Byron’s autobiographical writings have suffered from a chequered history. An 1809 record of his life and thoughts was destroyed at the behest of another friend, John Cam Hobhouse, on the grounds that it contained “objectionable passages”, and Byron later commented ruefully that Hobhouse “had robbed the world of a treat”.1

This pattern would be repeated. Between 1818 and 1821, Byron compiled a memoir (he observed to the publisher John Murray that some material “could not be used… for three hundred years to come”), again given to Thomas Moore. Portions were circulated to the literary world, but Byron continued to wobble over publication, and on his death in Greece in 1824 (aged only 36), Hobhouse, Murray and Moore met to discuss what should be done. The meeting was acrimonious and as the only one in favour of preserving the memoirs, Moore even suggested he and Murray should duel over the matter.2 But Murray and Hobhouse prevailed, and again the memoirs were destroyed. Are other copies still out there somewhere? It’s a literary mystery that remains unsolved!

In 1830, Moore did at least manage to compile what he could of Byron’s life, and published Letters and Journals of Lord Byron: With Notices of His Life.3 The Ravenna Journal was included there, one of four diaries by Byron that have survived (the first two I mentioned above; the last was in Greece in 1823).4

Byron headed to Ravenna in 1819, in hot pursuit of the Contessa Guiccioli – still just in her teens, she was married to a diplomat 50 years older than her. At this point Byron was 31 and well known as a literary celebrity, as well as for his sexual liaisons with both women and men. His fellow bon viveur Shelley visited, but even he couldn’t keep up with Byron’s lifestyle for too long, writing in a letter to Thomas Love Peacock in August 1821:

Lord Byron gets up at two. I get up, quite contrary to my usual custom (but one must sleep or die…), at twelve. After breakfast we sit talking till six. From six till eight we gallop through the pine forests which divide Ravenna from the sea; we then come home and dine, and sit up gossiping till six in the morning. I don’t suppose this will kill me in a week or fortnight, but I shall not try it longer. Lord Byron’s establishment consists, besides servants, of ten horses, eight enormous dogs, three monkeys, five cats, an eagle, a crow, and a falcon; and all these, except the horses, walk about the house…

The Ravenna Journal gives us an intimate account of Byron’s days, all the more tantalising for those lost memoirs. On 4th January, he writes:

This morning I gat me up late, as usual – weather bad – bad as England – worse. The snow of last week melting to the sirocco of to-day, so that there were two d—d things at once. Could not even get to ride on horseback in the forest. Stayed at home all the morning – looked at the fire – wondered when the post would come. Post came at the Ave Maria, instead of half-past one o’clock, as it ought. Galignani’s Messengers, six in number – a letter from Faenza, but none from England. Very sulky in consequence (for there ought to have been letters), and ate in consequence a copious dinner; for when I am vexed, it makes me swallow quicker – but drank very little.

He reads the papers, and is amused by a detail in a newspaper account of a “gypsy woman accused” of murder – she visited a grocer in Kent and the bacon she bought was wrapped in a page from the novelist Samuel Richardson’s Pamela. “What would Richardson, the vainest and luckiest of living authors… have said, could he have traced his pages from their place on the French prince’s toilets [an allusion to an anecdote from Dr Johnson] to the grocer’s counter and the gipsy-murderess’s bacon!!!”

At 8pm, he jumps in a carriage to visit La Contessa – “found her playing on the piano-forte, talked till ten” when her father and brother returned from the theatre. Next day, he “rose late – dull and drooping – the weather dripping and dense”. He eats, he reads. He goes out again:

Hear the carriage – order pistols and great coat, as usual necessary articles. Weather cold – carriage open, and inhabitants somewhat savage – rather treacherous and highly inflamed by politics. Fine fellows, though… Clock strikes – going out to make love. Somewhat perilous, but not disagreeable.

Last note of the day: “I will go to bed, for I find that I grow cynical.”

And the truth is, Byron was bored. Despite his lively affair with the Contessa and his household menagerie, this legendary consumer of experience could not find simple contentment. Perhaps some of this was the lassitude we all feel at this grey point of the year – but as the entry I share below suggests, the problem had deeper roots.

6th January, 1821

Mist – thaw – slop – rain. No stirring out on horseback. Read Spence’s Anecdotes. Pope a fine fellow – always thought him so. Corrected blunders in nine apophthegms of Bacon – all historical – and read Mitford’s Greece.5 Wrote an epigram…

At eight went out to visit. Heard a little music – like music. Talked with Count Pietro G[amba]. of the Italian comedian Vestris, who is now at Rome – have seen him often act in Venice – a good actor – very… He has made me frequently laugh and cry, neither of which is now a very easy matter – at least, for a player to produce in me…

Came home, and read Mitford again, and played with my mastiff – gave him his supper… My crow is lame of a leg – wonder how it happened – some fool trod upon his toe, I suppose. The falcon pretty brisk – the cats large – owl noisy – the monkeys I have not looked to since the cold weather, and they suffer by being brought up[stairs]. Horses must be gay – get a ride as soon as weather serves. Deuced muggy still – an Italian winter is a sad thing, but all the other seasons are charming.

What is the reason that I have been, all my lifetime, more or less ennuyé? and that, if any thing, I am rather less so now than I was at as far as my recollection serves? I do not know how to answer this, but presume that it is constitutional, – as well as the waking in low spirits, which I have invariably done for many years. Temperance and exercise, which I have practiced at times, and for a long time – together vigorously and violently, made little or no difference. Violent passions did; – when under their immediate influence – it is odd, but, I was in agitated, but not in depressed spirits.

A dose of salts has the effect of a temporary inebriation, like light champagne, upon me. But wine and spirits make me sullen and savage to ferocity – silent, however, and retiring, and not quarrelsome, if not spoken to. Swimming also raises my spirits, – but in general they are low, and get daily lower. That is hopeless: for I do not think I am so much ennuyé as I was at nineteen. The proof is, that then I must game, or drink, or be in motion of some kind, or I was miserable. At present, I can mope in quietness; and like being alone better than any company – except the lady’s whom I serve. But I feel a something, which makes me think that, if I ever reach near to old age, like Swift, “I shall die at top” first [Swift was comparing himself with an old tree]. Only I do not dread idiotism or madness so much as he did. On the contrary, I think some quieter stages of both must be preferable to much of what men think the possession of their senses.

We’ve met another side of Byron here before:

And here are some more literary giants struggling with melancholy:

In the words of Colonel Leicester Stanhope, who shared his reminiscences of Byron in Greece, in 1823 and 1824.

Much has been written about the meeting and who was most to blame – a story for another time here, perhaps, but you can read more about it in a 1959 article in The Atlantic here, for example.

The History of Greece, by William Mitford.

Really enjoyed reading this. I have always been a great fan of Byron's (Both for his work and the kind of paradox of his character - though, obviously, there are certain elements of his personality that are really quite horrible too!)

So it is such a shame that such a quantity of his autobiographical writings were destroyed. But still, any chance to read some of the man's most personal thoughts is really brilliant.

Thank you for sharing.