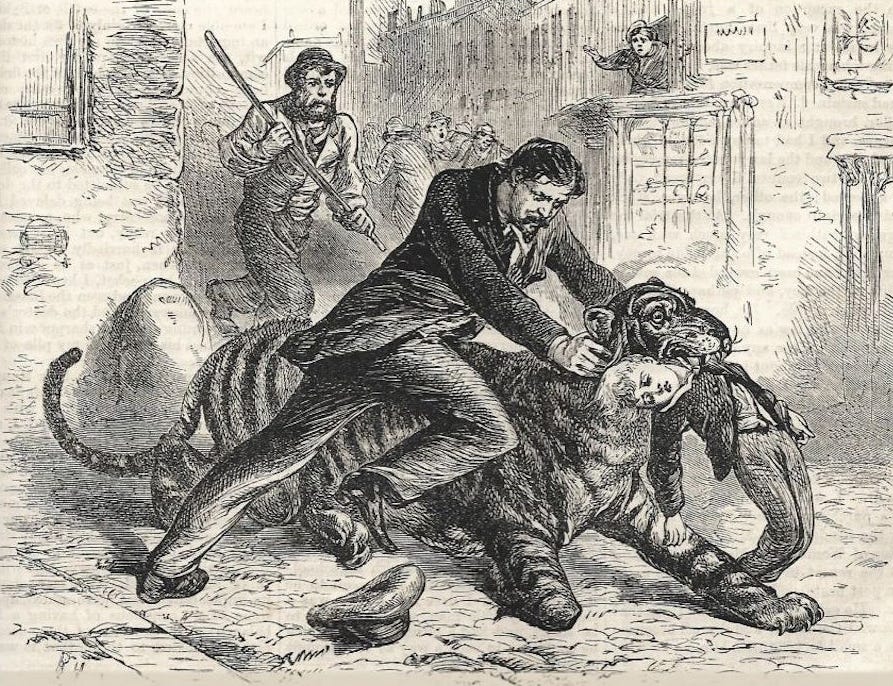

Tiger attack, 1857

But the details vary somewhat…

The tiger seized him by the shoulder and ran down the street with the lad hanging in his jaws…

I’ve commented before on unreliable narrators of events in the past and the tricksiness of finding ‘the truth’ about what really happened. This week I bring you a dramatic little story which epitomises these challenges.

First, let’s set the scene. Today, 29th July, happens to be International Tiger Day, so a tiger-themed story seems apt. At Tobacco Dock in Wapping, East London there’s a statue/sculpture (see below) depicting a boy looking awestruck at a tiger, which has a threateningly raised paw. (I haven’t managed to establish who the artist is or when it was installed, although it was perhaps when the dock was redeveloped as a shopping mall in 1989.)

Here’s what the caption under a companion statue of a bear says:

Over a hundred years ago on what was then called Ratcliffe Highway near to this spot stood Jamrach’s Emporium. This unique shop sold not only the most varied collection of curiosities but also traded in wild animals such as alligators, tigers, elephants, monkeys and birds… The animals were housed in iron cages and were well looked after until they were bought by zoological institutes and naturalist collectors.

And under the boy and tiger it reads:1

In the early years of the nineteenth century a full grown Bengal tiger, having just arrived at Jamrach’s Emporium, burst open his wooden transit box and quietly trotted down the road. Everybody scattered except an eight year-old boy, who, having never seen such a large cat, went up to it with the intent of stroking its nose. A tap of the great soft paw stunned the boy and, picking him up by his jacket, the tiger walked down a side alley. Mr. Jamrach, having discovered the empty box, came running up and, thrusting his bare hands into the tiger’s throat, forced the beast to let his captive go. The little boy was unscathed and the subdued tiger was led back to his cage. In memory of Jamrach’s any money collected from the fountain [opposite] will be donated to the World Wildlife Fund.

(Today’s International Tiger Day is also in support of the WWF, as it happens.)

Now, the tale as told there turns out to be fanciful at best – and my efforts to push back through time to the origins of the story reveal numerous inconsistencies and embellishments. More on that shortly!

Johann Christian Carl Jamrach was born in Germany in 1815. By his own account his father was chief of the Hamburg river police and used his connections with sailors to start trading in wild animals. The son – who became Charles on coming to England in the 1840s – then developed this business and became London’s leading dealer in wild animals. He set up shop in the East End, with Jamrach’s Animal Emporium at Nos 179/180 on what was the notorious Ratcliffe Highway (scene of some gruesome murders in 1811, and widely known as a den of crime) – now just ‘The Highway’ – as well as keeping a menagerie in Betts Street and a warehouse in Old Gravel Lane, both nearby. Charles Jamrach became renowned throughout the second half of the 19th century for his trade, and is mentioned in passing in Dracula and other literary works. He supplied animals to showmen P.T. Barnum and George Wombwell and was clearly the go-to guy for exotic fauna – with a touch of the showman himself. Whether the animals were as “well looked after” as the plaque above suggests is another matter – one contemporary account I’ve found suggests regular use of crowbars to subdue the beasts, and even a specialised tomahawk to tame the rhinos.

But back to the story of the boy and the tiger – a very different one from The Life of Pi. It turns out that Jamrach himself (who died in 1891, with his family continuing the business until 1919) wrote an account of what happened. Let’s turn to that next. It was published as ‘My struggle with a tiger’ in the 1st February 1879 edition of The Boy’s Own Paper – more than 20 years after the events it describes.2

It is now a good many years ago, when one morning a van-load of wild beasts, which I had bought the previous day from a captain in the London Docks, who brought them from the East Indies, arrived at my repository in Bett Street, St. George’s in-the-East. I myself superintended the unloading of the animals, and had given directions to my men to place a den containing a very ferocious full-grown Bengal tiger, with its iron-barred front close against the wall.

They were proceeding to take down a den with leopards, when all of a sudden I heard a crash, and to my horror found the big tiger had pushed out the back part of his den with his hind-quarters, and was walking down the yard into the street, which was then full of people watching the arrival of this curious merchandise… As soon as he got into the street, a boy of about nine years of age put out his hand to stroke the beast’s back, when the tiger seized him by the shoulder and ran down the street with the lad hanging in his jaws. This was done in less time than it takes me to relate; but when I saw the boy being carried off in this manner, and witnessed the panic that had seized hold of the people, without further thought I dashed after the brute, and got hold of him by the loose skin of the back of his neck. I was then of a more vigorous frame than now, and had plenty of pluck and dash in me.

I tried thus to stop his further progress, but he was too strong for me, and dragged me, too, along with him. I then succeeded in putting my leg under his hind legs, tripping him up, so to say, and he fell in consequence on his knees. I now, with all my strength and weight, knelt on him, and releasing the loose skin I had hold of, I pushed my thumbs with all my strength behind his ears, trying to strangulate him thus. All this time the beast held fast to the boy.

My men had been seized with the same panic as the bystanders, but now I discovered one lurking round a corner, so I shouted to him to come with a crowbar; he fetched one, and hit the tiger three tremendous blows over the eyes.

It was only now he released the boy. His jaws opened and his tongue protruded about seven inches. I thought the brute was dead or dying, and let go of him, but no sooner had I done so than he jumped up again. In the same moment I seized the crowbar myself, and gave him, with all the strength I had left, a blow over his head. He seemed to be quite cowed, and, turning tail, went back towards the stables, which fortunately were open. I drove him into the yard, and closed the doors at once. Looking round for my tiger, I found he had sneaked into a large empty den that stood open at the bottom of the yard. Two of my men, who had jumped on to an elephant’s box, now descended, and pushed down the iron-barred sliding-door of the den; and so my tiger was safe again under lock and key.

The boy was taken to the hospital, but with the exception of a fright and a scratch, was very little hurt. I lost no time in making inquiry about him, and finding where his father was, I offered him £50 as some compensation for the alarm he had sustained. Nevertheless, the father, a tailor, brought an action against me for damages, and I had to pay £300, of which he had £60, and the lawyers the remaining £240… At the trial the judge sympathised very much with me, saying that, instead of being made to pay, I ought to have been rewarded for saving the life of the boy, and perhaps that of a lot of other people… He suggested, however, as there was not much hurt done to the boy, to put down the damages as low as possible. The jury named £50, the sum I had originally offered to the boy’s father of my own good will. The costs were four times that amount. I was fortunate, however, to find a purchaser for my tiger a few days after the accident; for Mr. Edmonds, proprietor of Wombwell’s Menagerie, having read the report in the papers, came up to town post haste, and paid me £300 for the tiger. He exhibited him as the tiger that swallowed the child, and by all accounts made a small fortune with him.

[Oh, hang on, so the boy was 9, not 8. And Jamrach didn’t exactly thrust his hand down the tiger’s throat (understandably). Plus a keeper with a crowbar helped out. OK, fair enough. But in fact we also have an account by the keeper! This was published in The Leisure Hour on 17th June 1858 – only a few months after the actual events. This Christian magazine was edited then by James Macauley (Wikipedia notes he was a campaigner against animal cruelty, although if he wrote the following piece he was more excited than perturbed to see Jamrach’s collection). The article was entitled ‘Mr. Jamrach’s College for Young Beasts’ and I haven’t seen it referenced by other writers about the tiger story. Here’s an extract…3]

Mr. Jamrach now went away, handing me over to the guidance of his keeper—the keeper, I mean, of his wild animals. This keeper was a man almost as worthy of being studied as the animals under his charge. A very small man indeed; yet to him I found the credit was due of catching and bringing back the stray tigress. I found him full of anecdote… It was easier, he told me, to gain the confidence of a lion than a tiger; yet tigers and tigresses occasionally have very pretty ways. “That very tigress which escaped,” said he, “knew me well, and seemed to be very fond of me. Often when I was passing the front of her den, she would thrust out both paws, and beckon me towards her.” …

“Lions and tigers are often gentle enough whilst in their dens,” continued he, “but if by chance they break loose, their natural ferocity again possesses them. They forget all friendship then, and one must show them no favour or mercy. There is only one way to deal with them.”

“And what is that?”

“Knock them on the head at once—stun them. That is how I served the tigress. I felled her with the blow of a crowbar. For a time she lay like a thing dead, and when she recovered well enough to walk, oh what a tussle we had. She showed her teeth and pulled one way—I showed my crowbar and pulled the other way. She did not half like going back, I assure you; but I got the better of her at last.”

[Perhaps the keeper was ‘enhancing’ his own role in the story, but certainly there’s no mention of Jamrach’s self-avowed heroism. And the tiger is now female. The local vicar, Harry Jones, wrote his own brief account of the events in his 1875 book East and West London, where he says: “Presently the bravest spectator, armed with a crowbar, approached the tiger, and striking vehemently and blindly at him, missed the beast and killed the boy. The tiger was then secured.” Another dodgy memory, it seems. Thanks to the wonders of the British Newspaper Archive, I’ve pinned down the exact date of the escape – 26th October 1857 – and found some of the earliest reports. Here’s what the London Evening Standard had to say on the following day…]

EXTRAORDINARY ESCAPE OF A TIGER IN RATCLIFF-HIGHWAY

FRIGHTFUL ATTACK OF THE ANIMAL ON A BOY.

Yesterday, between twelve and one o’clock at noon, the inhabitants of St. George’s-in-the-East (alias Ratcliff-highway), were suddenly thrown into a state of the utmost alarm in consequence of the escape of a large tiger from the warehouse of Mr. Jamrach, the extensive importer of wild beasts, &c., of No. 180, Ratcliff-highway, whereby a boy, named John Wade, aged five years, was very seriously injured, and other parties’ lives were placed in great jeopardy.

It appears that yesterday morning Mr. Jamrach received several boxes, containing two tigers, a lion, and other animals, from the steam ship Germany, lying off Hambro’ Wharf, near the Custom House, Lower Thames-street, City. The packages were safely placed in a van, and conveyed to the warehouse in Betts-street, St. George’s-in the-East, followed by a crowd of men, women, and children, where a number of labourers adopted means to unload the vehicle. They had removed several boxes into the premises in safety, and had just lowered a large iron-bound cage on to the pavement in front of the gateway when Police-constable Stewart, 427 A, requested the persons standing round to keep back in case of an accident. The next moment the occupant (a fine full-sized tiger) became restless, and forced out one end of the cage, when the spectators rushed in every direction from the spot in a state of extreme terror. The tiger appeared to be in a state of madness, and ran along the pavement in the direction of Ratcliff-highway, where it seized the little boy, John Wade, by the upper part of the right arm. The enraged animal was followed by Mr. Jamrach and his men several yards, when the former obtained possession of a crowbar and struck the tiger upon the head and nose, which caused it to relinquish its hold. In the meanwhile ropes were procured, and the savage beast was secured and dragged into the premises, where it was firmly fastened up by the keepers.

The poor boy was raised up by Stewart, the police-officer, in a state of great suffering, with two severe lacerated wounds on the arm and right side of the face, and it was quite a miracle he was not torn to pieces. The teeth of the animal passed completely through the right arm.

A cab was procured, in which the wounded boy was conveyed to the London Hospital, where Mr. Forbes, the house surgeon, rendered every assistance. The boy was in a very low state from loss of blood from the wounds, and last evening, at seven o’clock, he was in a very precarious condition, both from the injuries and shock to the system through fright.

So now the boy is only 5, and we have his name, along with lots of other incidental detail – and Jamrach is the hero after all. And yet… on the very same day, the Morning Post reported that “a lad of about 11 years of age had fallen a victim to the beast’s fury… and in a moment was frightfully mangled… he now remains in a very precarious condition, and but slight hopes are entertained of his recovery”. Jamrach isn’t mentioned as being involved. Other papers on the same day echoes each version of the story. Some of this is perhaps down to better details emerging over time (or the time-honoured tradition of journalistic inaccuracy), and certainly more aspects of the story came out. Reynold’s Newspaper reported some years later, in February 1866, that the tiger itself was indeed put on show in Wombwell’s travelling menagerie, but caused further problems by attacking and killing a lion; and that Jamrach archly observed about being sued, “There was a lawyer as well as a tiger inside the tiger’s skin.”

Other newspapers reported about the legal action (Wade vs Jamrach) in February 1858: apparently Jamrach offered £10, not the £50 he later claimed. The boy – “a lad ten years old” – had physically recovered but was still traumatised and was plagued by night terrors. The judge praised Jamrach’s courage and awarded damages of £60 to the Wades. Further reports suggest a second boy had also been injured, but less badly – could this be why the ages vary?

All we can really conclude for certain here is that a tiger attacked a boy and was subdued, and that Jamrach himself was probably brave enough but also liked to talk up his heroism: marketing. And it just shows how even the smallest of stories from the past can be hard to pin down precisely.

It also transpires that Jamrach had had other tigers escape. In July 1877, the East London Observer reported that Jamrach had sent a tiger by train to a dealer in Liverpool, but it escaped somewhere before Rugby! It was tracked down to Northamptonshire by a man Jamrach sent on another train, leading one reporter to note, “The somewhat novel mode of hunting a tiger with a railway was witnessed near Rugby yesterday.” Eventually the poor beast was shot and sent back to Euston (by train, of course).

Unfortunately the statues are not accessible to the public now, other than when events are on at the Tobacco Dock exhibition/conference venue.

Charles Jamrach is the brother-in-law of my 3rd great-grandfather Michael Attanasio - Mary ( Attanasio) Jamrach's brother.

I loved reading this.