Interview with the vampire master, 1897

On the publicity treadmill

Though he did not say so, I am inclined to think that the literary agent is to him a nineteenth century vampire.

As I write this, yesterday was the 125th anniversary of the first publication of Dracula, which seems too good a theme to ignore. Actually the precise date of release is a little foggy now, but it is regarded as 26th May 1897 (just before another queen’s jubilee celebrations, as it happens) and it must have been around then because the first review (that I can find, anyway) was published on The Daily News on 27th May – and in fact the review was headed ‘Published to-day’.1

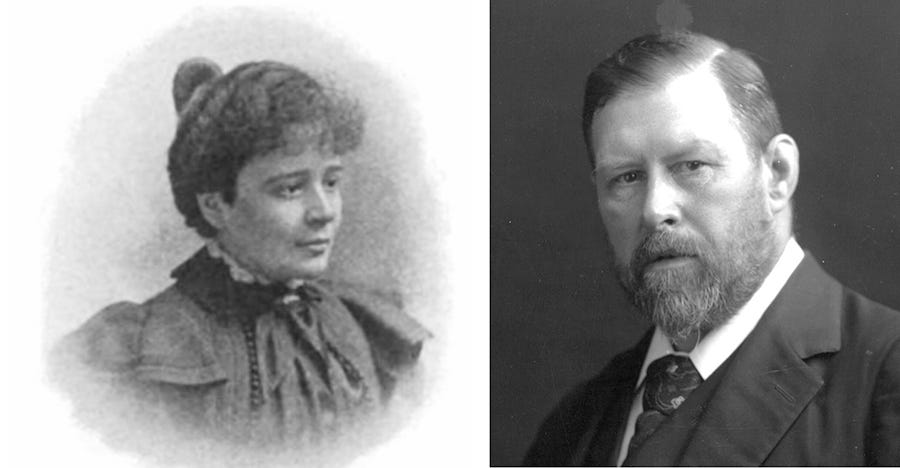

Its author, of course, was Abraham Stoker (1847–1912), better known as Bram. He was already well established as a writer, with four previous novels under his belt, along with lots of theatre criticism (his day job was as a theatre manager and personal assistant to the leading actor of the day, Sir Henry Irving) and other non-fiction.2

These days the release of a book by an established author tends to be accompanied by the round of publicity – reviews, interviews, blog tours, speaking events. I was interested to know whether this was the case 125 years ago. Certainly reviews had proliferated in all manner of journals and newspapers since at least the 18th century, often anonymously. Many were certainly published about Dracula over the subsequent months – the earliest one I can find with the actual reviewer’s name is one by William Leonard Courtney in the Daily Telegraph on 3rd June 1897. Here’s a little sample:

“Dracula,” at all events, is one of the most weird and spirit-quelling romances which have appeared for years. It begins in masterly fashion… Such is Mr. Stoker’s dramatic skill, that the reader hurries on breathless from the first page to the last, afraid to miss a single word…

After going down the rabbit hole about Courtney (whose grandson was Nicholas Courtney, who played the Brigadier for many years in Doctor Who), I discovered that in the early 1890s he was one of four men who had collaborated as directors of the Heinemann imprint ‘The English Library’. And one of the others was… Bram Stoker. Which just goes to show the nepotistic world of publishing and book reviews by authors’ mates is nothing new. (Among their published authors was Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, who was apparently distantly related to Bram Stoker. Doyle wrote Stoker a gushing fan letter about Dracula – “the very best story of diablerie which I have read for many years” – and ten years later Stoker interviewed Doyle for The Daily Chronicle.)

The history of interviews seems more elusive, and I’m going to come back to this another time. But did anyone interview Bram Stoker about his new book? We have one clear example, which is what I give you below. It was published as ‘Mr. Bram Stoker. A Chat with the Author of Dracula’ in the 1st July 1897 issue of British Weekly, subtitled ‘A Journal of Social and Christian Progress’. The interviewer’s name was only given as ‘Lorna’, but I was interested to know more about her.

The British Weekly ran from 1886 until the 1960s, and was founded by William Robertson Nicoll, a Scottish Free Church minister and journalist. In 1877 he met one Jane Thompson Stoddart (1863–1944) in Kelso, where he had moved and she had been born. He became her mentor and in due course as assistant editor on British Weekly, sometimes using the pseudonym Lorna, she effectively ran the paper. She wrote numerous books, some but by no means all on Christian or socialist themes, and an autobiography, My Harvest of the Years,3 in 1938, only a year after the Dictionary of National Biography says she retired.

Stoddart begins her article4 with an overview of Dracula and its plot (“although in some respects this is a gruesome book, it leaves on the mind an entirely wholesome impression”), but let’s jump to the actual interview…

On Monday morning I had the pleasure of a short conversation with Mr. Bram Stoker, who, as most people know, is Sir Henry Irving’s manager at the Lyceum Theatre. He told me, in reply to a question, that the plot of the story had been a long time in his mind, and that he spent about three years in writing it. He had always been interested in the vampire legend.

“It is undoubtedly,” he remarked, “a very fascinating theme, since it touches both on mystery and fact. In the Middle Ages the terror of the vampire depopulated whole villages.”

“Is there any historical basis for the legend?”

“It rested, I imagine, on some such case as this. A person may have fallen into a death-like trance and been buried before the time. Afterwards the body may have been dug up and found alive, and from this a horror seized upon the people, and in their ignorance they imagined that a vampire was about. The more hysterical, through excess of fear, might themselves fall into trances in the same way; and so the story grew that one vampire might enslave many others and make them like himself. Even in the single villages it was believed that there might be many such creatures. When once the panic seized the population, their only thought was to escape.”

“In what parts of Europe has this belief been most prevalent?”

“In certain parts of Styria [a state in south-east Austria] it has survived longest and with most intensity, but the legend is common to many countries, to China, Iceland, Germany, Saxony, Turkey, the Chersonese [this is Kherson in Ukraine], Russia, Poland, Italy, France, and England, besides all the Tartar communities.”

“In order to understand the legend, I suppose it would be necessary to consult many authorities?”

Mr. Stoker told me that the knowledge of vampire superstitions shown in “Dracula” was gathered from a great deal of miscellaneous reading.

“No one book that I know of will give you all the facts. I learned a good deal from E. Gerard’s ‘Essays on Roumanian Superstitions’, which first appeared in the Nineteenth Century, and were afterwards published in a couple of volumes. I also learned something from Mr. Baring-Gould’s ‘Were-Wolves.’ Mr. Gould has promised a book on vampires, but I do not know whether he has made any progress with it.”

[Sabine Baring-Gould’s The Book of Were-Wolves came out in 1865 and A Book of Ghosts in 1904 but a vampire book never transpired. Interestingly he wrote at a standing desk, so that’s another idea that’s not new. Many of Stoker’s fascinating research notes have been published in Bram Stoker’s Notes for Dracula by Robert Eighteen-Bisang and Elizabeth Miller, McFarland & Co., 2008. Stoddart continues…]

Readers of “Dracula” will remember that the most famous character in it is Dr. Van Helsing, the Dutch physician, who, by extraordinary skill, self-devotion, and labour, finally outwits and destroys the vampire. Mr. Stoker told me that van Helsing is founded on a real character. [There are too many theories about who this was to go into here.] In a recent leader on “Dracula,” published in a provincial newspaper, it is suggested that high moral lessons might be gathered from the book. I asked Mr. Stoker whether he had written with a purpose, but on this point he would give no definite answer.

“I suppose that every book of the kind must contain some lesson,” he remarked; “but I prefer that readers should find it out for themselves.”

[Here I’ll skip the interviewer’s details of Stoker’s early career and previous writings.]

He has been in London for some nineteen years, and believes that London is the best possible place for a literary man. “A writer will find a chance here if he is good for anything; and recognition is only a matter of time.” Mr. Stoker speaks of the generosity shown by literary men to one another in a tone which shows that he, at least, is not disposed to quarrel with the critics.

Mr. Stoker does not find it necessary to publish through a literary agent. It always seems to him, he says, that an author with an ordinary business capacity can do better for himself than through any agent.

“Some men now-a-days are making ten thousand a year by their novels, and it seems hardly fair that they should pay ten or five percent of this great sum to a middleman. By a dozen letters or so in the course of the year they could settle all their literary business on their own account.” Though Mr. Stoker did not say so, I am inclined to think that the literary agent is to him a nineteenth century vampire.

No interview during this week would be complete without a reference to the Jubilee, so I asked Mr. Stoker, as a Londoner of nearly twenty years’ standing, what he thought of the celebrations.

“Everyone,” he said, “has been proud that the great day went off so successfully. We have had a magnificent survey of the Empire, and last week’s procession brought home, as nothing else could have done, the sense of the immense variety of the Queen’s dominions.”

More on that next week, no doubt…

And speaking of bloodsuckers, if you haven’t heard yet, I’ve now launched a new paid subscription – this will help support the many hours of research that Histories entails, and in return you’ll receive the new quarterly/annual edition in your chosen format (including a print option).

On 24th May, Stoker wrote a letter to his friend William Gladstone, the former prime minister, sending him a copy of the book, which he says was coming out on 26th May.

www.bramstoker.org has a useful bibliography.

It’s online here. Sadly it doesn’t mention her interview with Stoker. She notes: “My own contributions of this kind to the British Weekly amounted in the course of years to several hundreds.”

The article is reproduced in Bram Stoker’s Dracula: A Documentary Volume edited by Elizabeth Miller (Thomson Gale, 2005), which contains many other useful sources.