The ringing of the shop-door bell, 1773-80

Enter for snuff, sugar and wit

(Hello, this is Histories, a free weekly email exploring first-hand accounts from the corners of history… Do please share this with fellow history fans and subscribe.)

Look’ye Sir, I write to the ringing of the shop-door bell—I write—betwixt serving—gossiping—and lying. Alas! what cramps to poor genius!

Last week we met Ignatius Sancho (1729–80), Britain’s first black person to get the vote, a staunch campaigner for the abolition of slavery, a prolific article writer and composer, and an eyewitness of the Gordon Riots of 1780. Sancho is known to us today through his letters first published in 17821 – and one particularly well-known sequence is a lively correspondence between him and the author Lawrence Sterne about slavery.2

But here I’d like to focus on more domestic scenes, through the prism of Sancho’s role as a shopkeeper, running his own shop at 19–20 Charles Street Mayfair – his letters yield charming details of his business, his family and daily trials and joys, and indeed it was this shop, a few streets from Parliament, that helped him know many luminaries of his day.

[Sancho moved to Charles Street in 1773. The house was built in 1750 and still stands, in altered form. It was later the family home of the 5th Earl of Rosebery, prime minister 1894–5. One of Sancho’s helpers in setting up shop was ‘Mrs H’, whose name we don’t know (possibly Howard) but appears to have been a fellow servant in the household of the late Duke of Montagu, Ignatius’s benefactor. He wrote this to her about his plans:]

1st November, 1773

I have sincere pleasure to find you honor me in your thoughts… Part of your scheme we mean to adopt—but the principal thing we aim at is in the tea, snuff, and sugar, with the little articles of daily domestic use—in truth, I like your scheme, and I think the three articles you advise would answer exceeding well—but it would require a capital—which we have not—so we mean to cut our coat according to our scanty quantum—and creep with hopes of being enabled hereafter to mend our pace.

[Here Sancho refers to his wife having given birth to their fifth daughter, Kitty. He married Anne Osborne, of West Indian descent, in 1758, and they had seven children.]

Mrs. Sancho is in the straw—she has given me a fifth wench… as soon as we can get a bit of house, we shall begin to look sharp for a bit of bread—I have strong hope—the more children, the more blessings—and if it please the Almighty to spare me from the gout, I verily think the happiest part of my life is to come—soap, starch, and blue, with raisins, figs, &c.—we shall cut a respectable figure—in our printed cards.—Pray make my best wishes to Mr. H——; tell him I revere his whole family, which is doing honor to myself.

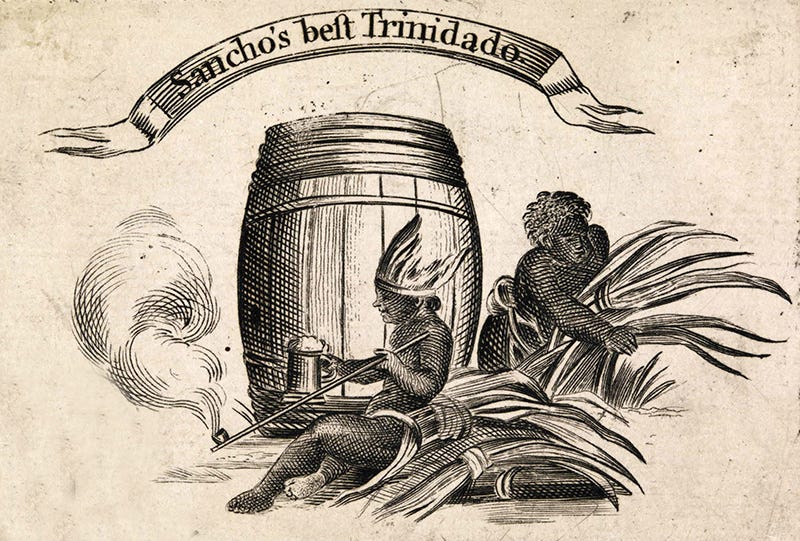

[See above for his printed trade card – the other side refers to ‘Sancho’s Best Trinidado’, a blend of tobacco. Somewhat unfortunately he sold goods which at the time relied upon the slavery to which he was opposed. A couple of months later, his shop was up and running:]

9th February, 1774

I opened shop on Saturday the 29th of January—and have met with a success truly flattering;—it shall be my study and constant care not to forfeit the good opinion of my friends…

[Two years later he grumbles about poor business. William is his young son, born the previous October.]

28th August, 1776

… More and more convinced of the futility of all our eagerness after worldly riches, my prayer and hope is only for bread, and to be enabled to pay what I owe;—I labour up hill against many difficulties—but God’s goodness is my support—and his word my trust.—Mrs. Sancho joins me in her best wishes, and gives you joy also; the children are all well—William grows, and tries his feet briskly—and Fanny goes on well in her tambour-work—Mary must learn some business or other—if we can possibly achieve money—but we have somehow no friends—and, bless God!—we deserve no enemies. Trade is duller than ever I knew it—and money scarcer;—foppery runs higher—and vanity stronger;—extravagance is the adored idol of this sweet town.

[Sancho often refers to his sufferings from gout, here in a letter to his good friend John Meheux, a clerk at the India Board, described in another letter as “the best friend and customer I have”.]

4th December, 1776

I forgot to tell you this morning—a jack-ass would have shewn more thought—…the best recipe for the gout, I am informed—is two or three stale Morning-Posts;—reclined in easy chair—the patient must sit—and mull over them—take snuff at intervals—hem—and look wife;—I apply to you as my pharmacopolist—do not criticize my orthography—but when convenient—send me the medicine—which, with care and thanks, I will return.

[He picks up on the ‘jack-ass’ theme again, that being the title of this letter to Meheux:]

25th August, 1777

My gall has been plentifully stirred—by the barbarity of a set of gentry, who every morning offend my feelings—in their cruel parade through Charles Street to and from market—they vend potatoes in the day—and thieve in the night season.—A tall lazy villain was bestriding his poor beast (although loaded with two panniers of potatoes at the same time) and another of his companions, was good-naturedly employed in whipping the poor sinking animal—that the gentleman-rider might enjoy the two-fold pleasure of blasphemy and cruelty—this is a too common evil—and, for the honor of rationality, calls loudly for redress.—I do believe it might be in some measure amended--either by a hint in the papers, of the utility of impressing such vagrants for the king’s service—or by laying a heavy tax upon the poor Jack-asses…

Mrs. Sancho would send you some tamarinds.—I know not her reasons;—as I hate contentions, I contradicted not—but shrewdly suspects she thinks you want cooling;—do you hear, Sir?

[In another letter, we learn more of his affection for his young son.]

24th October, 1777

You cannot imagine what hold little Billy gets of me—he grows—prattles—every day learns something new—and by his good-will would be ever in the shop with me—The monkey! he clings round my legs—and if I chide him or look sour, he holds up his little mouth to kiss me.—I know am the fool for parents’ weakness is child’s strength:—truth orthodox which will hold good between lover and lovee...

[In this next letter, Sancho refers to the American War of Independence, before turning to matters closer to hand and another little scene in his shop:]

“I… I sincerely believe the Sacred Writ—and of course look upon war in all its horrid arrangements as the bitterest curse that can fall upon a people—and this American one—as one of the very worst—of worst things… But let me return, if possible, to my senses;—for God’s sake! what has a poor starving Negroe, with six children, to do with kings and heroes, and armies and politics?—aye, or poets and painters?—or artists—of any sort?… I am resolved, from henceforth, to banish feelings—Misanthrope from head to foot!—Apropos—not five minutes since I was interrupted, in this same letter of letters, by a pleasant affair—to a man of no feelings.—

A fellow bolted into the shop—with a countenance in which grief and fear struggled for mastery.

“Did you see any body go to my cart, Sir?”

“No, friend, how should I? you see I am writing—and how should I be able to see your cart or you either in the dark?”

“Lord in heaven pity me!” cries the man, “what shall I do? oh! what shall I do?—I am undone!—Good God!—I did but go into the court here—with a trunk for the lady at Captain G——’s (I had two to deliver) and somebody has stole the other;—what shall I do?—what shall I do?”

“Zounds, man!—who ever left their cart in the night with goods in it, without leaving some one to watch?”

“Alack, Sir, I left a boy, and told him I would give him something to stand by the cart, and the boy and trunk are both gone!”

Oh nature!—oh heart!—why does the voice of distress so forcibly knock at the door of hearts?—but to hint to pride and avarice—our common kindred—and to alarm self-love.… But this same stolen trunk;—the ladies are just gone out of my shop—they have been here holding a council—upon law and advertisements;—God help them!—they could not have come to a worse—nor could they have found a stupider or sorrier adviser:—the trunk was seen parading between two in the Park—and I dare say the contents by this time are pretty well gutted…

… How can you expect business in these hard times—when the utmost exertions of honest industry can scarce afford people in the middle sphere of life daily provisions?—When it shall please the Almighty that things shall take a better turn in America—when the conviction of their madness shall make them court peace—and the same conviction of our cuelty and injustice induce us to settle all points in equity—when that time arrives, my friend, America will be the grand patron of genius—trade and arts will flourish—and if it shall please God to spare us till that period—we will either go and try our fortunes there—or stay in Old England and talk about it…

[Another of his regular correspondents was a Mrs Margaret Cocksedge, godmother to Kitty, and from what Sancho writes, he appears to have been very attracted to her, despite his obvious devotion to his wife (unlike our previous Histories shopkeeper). Here he offers her some grocer’s advice:]

23rd July, 1778

… let us know by the next post that you are well, and mean to take every prudent step so to continue—that you have left off tea, I do much approve of—but insist that you make your visitors drink double quantity—that I may be no loser—I hope you find cocoa agree with you—it should be made always over night, and boiled for above fifteen minutes—but you must caution Miss C—not to drink it—for there is nothing so fattening to little folks…

[Soon after, young Kitty’s health was failing – in 1775 we read she was “as lively as ever” but by September 1778 “Kitty has been very poorly for above a month past”. Two letters refer movingly to her death.]

9th March, 1779

… for these six past weeks, our days have been clouded by the severe illness of a child—whom it has pleased God to take from us: and a cowardly attack of the gout at a time when every exertion was needful…

11th March

I give you due credit for your sympathizing feelings on our recent very distressful situation—for thirty nights (save two) Mrs. Sancho had no cloaths off—but you know the woman. Nature never formed a tenderer heart—take her for all in all—the mother—wife—friend—she does credit to her sex—she has the rare felicity of possessing true virtue without arrogance—softness without weakness—and dignity without pride… and to my inexpressible happiness, she is my wife—and truly best part—without a single tinge of my defects.—Poor Kitty! happy Kitty I should say, drew her rich prize early—wish her joy! … Pox on it, my hand aches so, I can scrawl no longer.—Mrs. Sancho is but so, so—the children are well—do write large and intelligible when you write to me, I hate fine hands and fine language—write plain honest nonsense, like thy true friend, I. SANCHO.

[A year later, Sancho’s own health was failing and the gout had taken greater hold of him. He offers his friend Mr Wingrave, a bookseller, some reading recommendations.]

5th January, 1780

I recommend all young people, who do me the honour to ask my opinion—I recommend, if their stomachs are strong enough for such intellectual food—Dr. Young’s Night-Thoughts—the Paradise Lost—and the Seasons;—which with Nelson’s Feasts and Fasts—a Bible and Prayer-book—used for twenty years to make my travelling library…

I feel old age insensibly stealing on me—and, alas! am obliged to borrow the aid of spectacles, for any kind of small print:—Time keeps pacing on, and we delude ourselves with the hope of reaching first this stage, and then the next;—till that ravenous rogue Death puts a final end to our folly.

[This is the last letter we have from Ignatius, to his friend John Spink. Sancho died a week later. When he was an adult William turned the premises into a bookshop and printing house.]

7th December, 1780

DEAR SIR,

I AM doubly and trebly happy, that I can in some measure remove the anxiety of the best couple in the universe. I set aside all thanks—for were I to enter into the feelings of my heart for the past and present, I should fill the sheet: but you would not be pleased.—In good truth, I have been exceeding ill—my breath grew worse—and the dropsy made large strides.—I left off medicine by consent for four or five days, swelled immoderately:—the good Dr. [Norford] eighty miles distant—and Dr. Jebb heartily puzzled through the darkness of his patient.—I began to feel alarm—when, looking into your letter, I found a Dr. S—th recommended by yourself. I enquired—his character is great—but for lungs and dropsy, Sir John [Elliot], physician extraordinary, and ordinary to his Majesty, is reckoned the first. I applied to him on Sunday morning—he received me like Dr. [Norford];—I have faith in him.—My poor belly is so distended, that I write with pain—I hope next week to write with more ease. My dutiful respects await Mrs. S[pink] and self, to which Mrs. Sancho begs to be joined by her loving husband, and

Your most grateful friend,

SANCHO.

John Thomas Smith, author of a biography of the sculptor Joseph Nollekens (the book was known for its ‘malicious candour’), visited Sancho’s shop six months before the grocer died, and gives us a lasting image of the scene in Charles Street:

In June 1780, Mr. Nollekens took me to the house of Ignatius Sancho, who kept a grocer’s, or rather chandler’s shop, at No. 20 Charles-street, Westminster… This extraordinary literary character… was born on board a slave-ship in 1729… In his leisure hours he indulged his taste for music, painting, and literature; which procured him the acquaintance of several persons of distinction.

… as we pushed the wicket-door, a little tinkling bell, the usual appendage of such shops, announced its opening: we drank tea with Sancho and his… lady, who was seated, when we entered, chopping sugar, surrounded by her little ‘Sanchonets’.3

Sancho’s own term for his brood.

A literate, thoughtful man - a different and interesting perspective on life in the eighteenth century. Glad I have found your Substack and subscribed. :)

Surely, in the entry for 4th December, he wrote " . . . and look wise" (the usual f/s mixup).