The shouts of the mob, 1780

London's worst riot seen at close quarters

(Hello, this is Histories, a free weekly email exploring first-hand accounts from the corners of history… Do please share this with fellow history fans and subscribe.)

There is at this present moment at least a hundred thousand poor, miserable, ragged rabble, from twelve to sixty years of age, with blue cockades in their hats… all parading the streets—the bridge—the park—ready for any and every mischief.

I mentioned a couple of weeks ago that there were as many as 20,000 black people in Georgian London. One of them was Charles Ignatius Sancho (c.1729–1780), who had been sold into slavery in New Grenada, and given to three sisters in Greenwich when he was just two. As a young adult, he fled and ended up as a valet to the peer John Montagu (1690–1749), who provided Ignatius with an education. He put this to good use, and became a leading member of the abolitionist movement in Britain; and in 1774 he was to become the first known black Briton to vote.

Sancho became a notable man of letters in his time, corresponding with figures such as Lawrence Sterne, and wrote many musical compositions and two plays as well as his many letters about slavery and other subjects. Those letters were published in 1782 as The Letters of the Late Ignatius Sancho, an African, and are well worth exploring.

As well as his writing work, in 1774 the industrious Ignatius set up a grocery shop at 19 Charles Street, Mayfair, selling tobacco, sugar and tea to a wide range of notables of his day, including the artist Thomas Gainsborough and the actor David Garrick. And it was that location which gave him a unique close-up view of the Gordon Riots of June 1780.

These riots began as a protest against the Papists Act 1778, which gave the first minor support for Catholicism since its suppression in the 17th century (although full Catholic emancipation took another 50 years). They were named after Lord George Gordon (1751–93), who founded the Protestant Association to campaign for the repeal of the Papists Act. On 2nd June 1780 he marched with a crown of around 50,000 people from south London to the Houses of Parliament, but the mob gradually got out of hand and ran amok for a week until the army was brought in.

Ignatius Sancho’s shop was on the rioters’ route, and through a series of letters to his friend the draper and banker John Spink, he has given us a remarkable eyewitness account of the chaos, written with great immediacy.1

June 6

In the midst of the most cruel and ridiculous confusion, I am now set down to give you a very imperfect sketch of the maddest people that the maddest times were ever plagued with.—The public prints have informed you (without doubt) of last Friday's transactions;—the insanity of Ld G G [i.e. Gordon] and the worse than Negro barbarity of the populace;2—the burnings and devastations of each night you will also see in the prints:—This day, by consent, was set apart for the farther consideration of the wished-for repeal;—the people (who had their proper cue from his lordship) assembled by ten o’clock in the morning.— Lord N [Lord North, the prime minister], who had been up in council at home till four in the morning, got to the house before eleven, just a quarter of an hour before the associators reached Palace-yard:—but, I should tell you, in council there was a deputation from all parties…

There is at this present moment at least a hundred thousand poor, miserable, ragged rabble, from twelve to sixty years of age, with blue cockades in their hats—besides half as many women and children—all parading the streets—the bridge—the park—ready for any and every mischief.—Gracious God! what's the matter now? I was obliged to leave off—the shouts of the mob—the horrid clashing of swords—and the clutter of a multitude in swiftest motion—drew me to the door—when every one in the street was employed in shutting up shop.—It is now just five o’clock—the ballad-singers are exhausting their musical talents—with the downfall of Popery… Lord Sh [Lord Sandwich – remembered today for his snack-loving – was another John Montagu, and a cousin of Sancho’s patron] was narrowly escaped with life about an hour since;—the mob seized his chariot going to the house, broke his glasses, and, in struggling to get his lordship out, they somehow have cut his face;—the guards flew to his assistance—the light-horse scowered the road, got his chariot, escorted him from the coffee-house, where he had fled for protection, to his carriage, and guarded him bleeding very fast home. This—this—is liberty! genuine British liberty!—This instant about two thousand liberty boys are swearing and swaggering by with large sticks—thus armed in hopes of meeting with the Irish chairmen and labourers—all the guards are out—and all the horse;—the poor fellows are just worn out for want of rest—having been on duty ever since Friday.—Thank heaven, it rains; may it increase, so as to send these deluded wretches safe to their homes, their families, and wives! About two this afternoon, a large party took it into their heads to visit the King and Queen, and entered the Park for that purpose—but found the guard too numerous to be forced, and after some useless attempts gave it up.—It is reported, the house will either be prorogued, or parliament dissolved, this evening—as it is in vain to think of attending any business while this anarchy lasts…

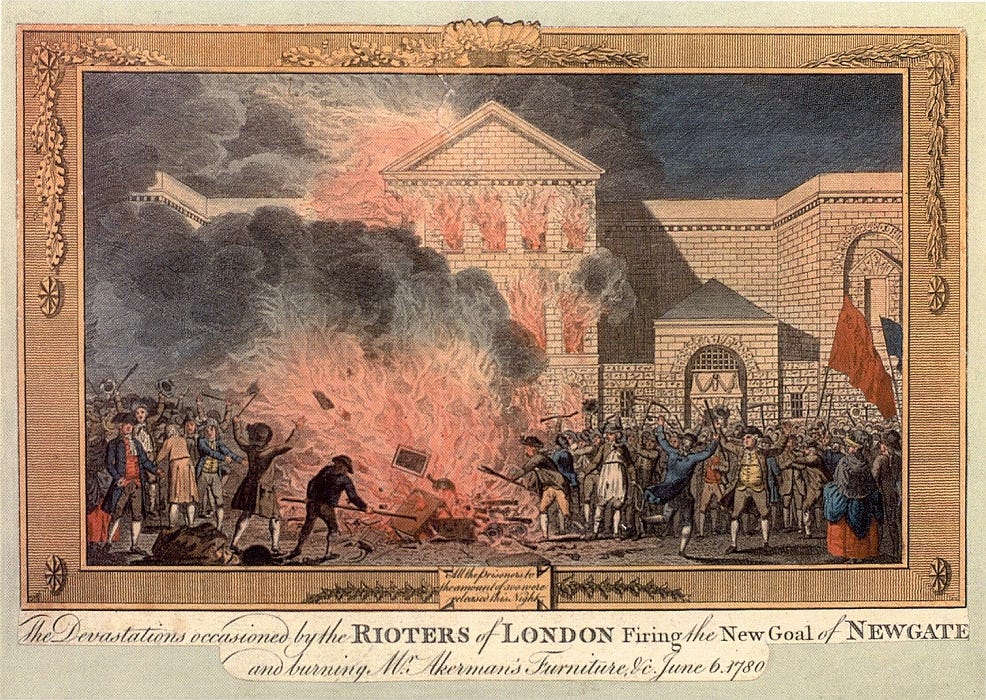

[In a postscript to this letter, Sancho then alludes to the rioters attacking Newgate Prison, releasing the inmates; the prison was largely destroyed – it took two years and £30,000 (now at least £4 million) to rebuild.]

There is about a thousand mad men, armed with clubs, bludgeons, and crows, just now set off for Newgate, to liberate, they say, their honest comrades.—I wish they do not some of them lose their lives of liberty before morning. It is thought by many who discern deeply, that there is more at the bottom of this business than merely the repeal of an act—which has as yet produced no bad consequences, and perhaps never might.—I am forced to own, that I am for universal toleration. Let us convert by our example, and conquer by our meekness and brotherly love!

Eight o’clock. Lord G[eorge] G[ordon] has this moment announced to my Lords the mob—that the act shall be repealed this evening:—upon this, they gave a hundred cheers—took the horses from his hackney-coach—and rolled him full jollily away:—they are huzzaing now ready to crack their throats

June 9

Government is sunk in lethargic stupor—anarchy reigns—when I look back to the glorious time of a George II and a Pitt’s administration—my heart sinks at the bitter contrast… the Fleet Prison, the Marshalsea, King’s-Bench, both Compters, Clerkenwell, and Tothill Fields, with Newgate, are all slung open;—Newgate partly burned, and 300 felons from thence only let loose upon the world.—Lord M’s [Lord Mansfield was a prime mover toward the abolition of slavery, and had supported the Papists Act] house in town suffered martyrdom; and his sweet box at Caen Wood escaped almost miraculously, for the mob had just arrived, and were beginning with it—when a strong detachment from the guards and light-horse came most critically to its rescue≥ Ld. N’s house was attacked; but they had previous notice, and were ready for them. The Bank, the Treasury, and thirty of the chief noblemen’s houses, are doomed to suffer by the insurgents.—There were six of the rioters killed at Ld M’s; and, what is remarkable, a daring chap escaped from Newgate, condemned to die this day, was the most active in mischief at Ld. M[ansfield]’s, and was the first person shot by the soldier; so he found death a few hours sooner than if he had not been released.—The ministry have tried lenity, and have experienced its inutility; and martial law is this night to be declared.—If any body of people above ten in number are seen together, and refuse to disperse, they are to be fired at without any further ceremony—so we expect terrible work before morning…

Half past nine o’clock. King’s-Bench prison is now in flames, and the prisoners at large; two fires in Holborn now burning.

[In a second letter on the same date, Sancho continues.]

Happily for us the tumult begins to subside—last night much was threatened, but nothing done—except in the early part of the evening, when about fourscore or an hundred of the reformers got decently knocked on the head… There is about fifty taken prisoners—and not a blue cockade to be seen:—the streets once more wear the face of peace—and men seem once more to resume their accustomed employments;—the greatest losses have fallen upon the great distiller near Holborn-bridge, and Lord M; the former, alas! has lost his whole fortune;—the latter, the greatest and best collection of manuscript writings, with one of the finest libraries in the kingdom.—Shall we call it a judgement?—or what shall we call it? The thunder of their vengeance has fallen upon gin and law—the two most inflammatory things in the Christian world…

Hyde Park has a grand encampment, with artillery… St. James’s Park has ditto—upon a smaller scale… We have taken this day numbers of the poor wretches, in so much we know not where to place them… bets run fifteen to five Lord G G is hanged in eight days…

June 13

The spring with us has been very sickly—and the summer has brought with it sick times—sickness! cruel sickness! triumphs through every part of the constitution:—the state is sick—the church (God preserve it!) is sick—the law, navy, army, all sick—the people at large are sick with taxes—the Ministry with Opposition, and Opposition with disappointment.—Since my last, the temerity of the mob has gradually subsided;—numbers of the unfortunate rogues have been taken:—yesterday about thirty were killed in and about Smithfield, and two soldiers were killed in the affray.—There is no certainty yet as to the number of houses burnt and gutted—for every day adds to the account—which is a proof how industrious they were in their short reign… The camp in St. James’s Park is daily increasing—that and Hyde Park will be continued all summer.—The [King] is much among them them—walking the lines—and examining the posts—he looks exceeding grave. Crowns, alas! have more thorns than roses.

In the end, nearly 500 rioters were either killed or wounded by the army, with as many again arrested – and more than twenty executed. Gordon was charged with high treason and imprisoned in the Tower of London but found not guilty – ironically eight years later he was imprisoned in Newgate for defamation; and surprisingly, given his Protestant protestations, in 1787 he converted to Judaism while living in Birmingham, and died in Newgate, aged 42, as Yisrael bar Avraham Gordon. There are various other first-hand accounts of the riots, as well as fictional versions (including in Charles Dickens’ Barnaby Rudge, 1841). As for Ignatius Sancho, he sadly died from the effects of gout only six months after the riots – but we shall meet him again in more peaceful times next week.

There are some great resources about Sancho and other black Britons of his era at Brycchan Carey’s website. Carey argues that Sancho’s letters are not as immediate as they seem, and partly drew from newspaper accounts. Though their tone seems real enough to me, and his shop was certainly on the way to Parliament!

An unfortunate phrase to our ears, but even though Sancho was black himself, and an ardent abolitionist, he clearly reflects the mores of the society he had entered.