The other Columbus, 1497

The Matthew heads west…

They saw manure of animals which they thought to be farm animals, and they saw a stick half a yard long pierced at both ends, carved and painted with brazil, and by such signs they believe the land to be inhabited…

I’ve written before about how it becomes much harder to find clear first-hand sources when we go back in time as far as five centuries ago – but we can still find people close to events, glimpses through the cracks of time.

Most people perhaps know that ‘Columbus sailed the ocean blue, in fourteen hundred and ninety-two’ – in fact, between 1492 and 1504, Columbus, a native of Genoa, Italy, made four voyages across the Atlantic, although technically none of them actually reached North America, as the furthest west he got was Cuba. However, another man, also from Genoa, did get to the North American coast, in 1497. According to some accounts it was 525 years ago to the day, on 20th May, although other versions say it was 2nd May.

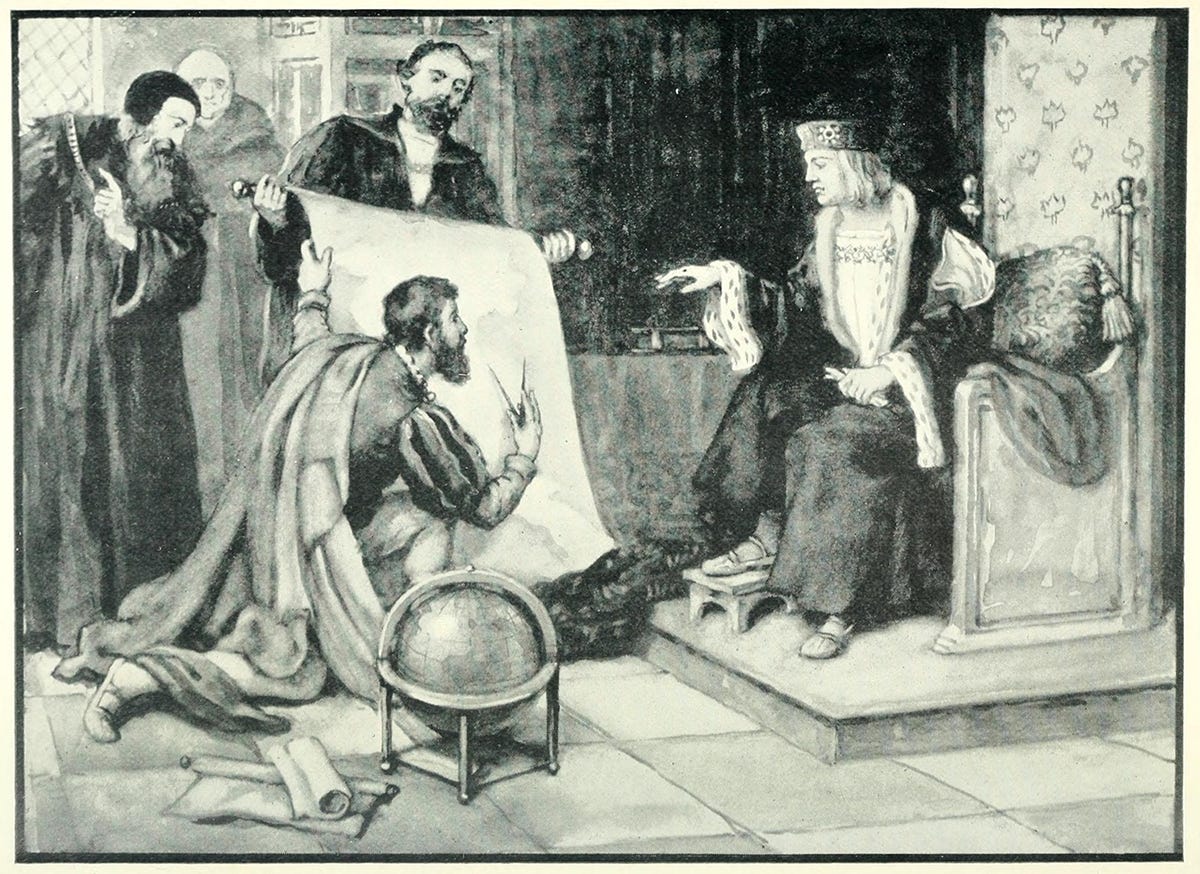

That man was Giovanni Caboto (c.1450–c.1500), more generally known by his Anglicised name, John Cabot. He was the first known European to have reached that coast since the Vikings did back in the 11th century. Cabot gained citizenship of Venice and became a sea trader, but got himself into financial difficulties – he then moved to Spain before seeking patronage and financial support in London.

On 5th March 1496, he was granted ‘letters patent’ by no less than King Henry VII to explore westward, as long as he didn’t tread on the toes of the Spanish or Portuguese. The full text of this grant is here, but the gist is:

Be it known and made manifest that we have given and granted… to our well beloved John Cabot, citizen of Venice, and to Lewis, Sebastian and Sancio, sons of the said John… full and free authority, faculty and power to sail to all parts, regions and coasts of the eastern, western and northern sea, under our banners, flags and ensigns, with five ships or vessels of whatsoever burden and quality they may be, and with so many and such mariners and men as they may wish to take with them in the said ships, at their own proper costs and charges, to find, discover and investigate whatsoever islands, countries, regions or provinces of heathens and infidels, in whatsoever part of the world placed, which before this time were unknown to all Christians. We have also… given licence to set up our aforesaid banners and ensigns in any town, city, castle, island or mainland whatsoever, newly found by them. And that the before-mentioned John and his sons or their heirs and deputies may conquer, occupy and possess whatsoever such towns, castles, cities and islands by them thus discovered that they may be able to conquer, occupy and possess…

Cabot made three voyages, all from Bristol, the leading port in England at the time for any westward journey. The first was stymied by bad weather, but the second, in June 1497, reached land. A chronicle from Bristol compiled until 15651 records tersely that:

This year, on St. John the Baptist’s Day [24th June], the land of America was found by the Merchants of Bristow in a shippe of Bristowe, called the Mathew; the which said ship departed from the port of Bristowe, the second day of May, and came home again the 6th of August next following.

More detailed sources are few in number, but there is one which gives more information than any other, from a merchant based in Bristol at the time. He was called John Day, or he wasn’t. Research by the late historian Alwyn Ruddock2 revealed that he was born Hugh Say and came from London. He moved to Bristol around 1494, by which time he was calling himself John Day, but around 1502 he returned to London… as Hugh Say again. At this time he also became embroiled in some legal disputes, one over the delivery or otherwise of 19 woollen cloths. Was he a reliable narrator, therefore? Ruddock notes: “Hugh Say’s last testament reveals him as a man who had travelled widely, lost most of his patrimony, committed deeds for which he despaired of making restitution and at the end had very little left to bequeath to his son and daughters.”

In late 1497/early 1498, he was in Spain on business, where he wrote the letter which tells us about Cabot. This letter (which only came to light in 1956) was addressed to the ‘Lord Grand Admiral’, who is in fact believed to be none other than Christopher Columbus himself. The letter survives in Spanish (Ruddock suggests it was translated by a native speaker at the time), and was translated (back) into English in 1962.3 And here is most of it…

Your Lordship’s servant brought me your letter. I have seen its contents and I would be most desirous and most happy to serve you… I am sending the other book of Marco Polo and a copy of the land which has been found [by Cabot]… from the said copy your Lordship will learn what you wish to know, for in it are named the capes of the mainland and the islands, and thus you will see where land was first sighted, since most of the land was discovered after turning back.

Thus your Lordship will know that the cape nearest to Ireland is 1800 miles west of Dursey Head which is in Ireland, and the southernmost part of the Island of the Seven Cities is west of Bordeaux River, and your Lordship will know that he landed at only one spot of the mainland, near the place where land was first sighted, and they disembarked there with a crucifix and raised banners with the arms of the Holy Father and those of the King of England, my master; and they found tall trees of the kind masts are made, and other smaller trees, and the country is very rich in grass. In that particular spot, as I told your Lordship, they found a trail that went inland, they saw a site where a fire had been made, they saw manure of animals which they thought to be farm animals, and they saw a stick half a yard long pierced at both ends, carved and painted with brazil, and by such signs they believe the land to be inhabited.

Since he was with just a few people, he did not dare advance inland beyond the shooting distance of a crossbow, and after taking in fresh water he returned to his ship. All along the coast they found many fish like those which in Iceland are dried in the open and sold in England and other countries, and these fish are called in English ‘stockfish’; and thus following the shore they saw two forms running on land one after the other, but they could not tell if they were human beings or animals; and it seemed to them that there were fields where they thought might also be villages, and they saw a forest whose foliage looked beautiful.

They left England toward the end of May, and must have been on the way 35 days before sighting land; the wind was east-north-east and the sea calm going and coming back, except for one day when he ran into a storm two or three days before finding land; and going so far out, his compass needle failed to point north and marked two rhumbs below. They spent about one month discovering the coast and from the above mentioned cape of the mainland which is nearest to Ireland, they returned to the coast of Europe in fifteen days.

They had the wind behind them, and he reached Brittany because the sailors confused him, saying that he was heading too far north. From there he came to Bristol, and he went to see the King to report to him all the above mentioned; and the King granted him an annual pension of twenty pounds sterling to sustain himself until the time comes when more will be known of this business, since with God’s help it is hoped to push through plans for exploring the said land more thoroughly next year with ten or twelve vessels—because in his voyage he had only one ship of fifty toneles and twenty men and food for seven or eight months—and they want to carry out this new project. It is considered certain that the cape of the said land was found and discovered in the past by the men from Bristol who found ‘Brasil’ as your Lordship well knows. It was called the Island of Brasil, and it is assumed and believed to be the mainland that the men from Bristol found.

[It’s worth pausing here to note that this appears to suggest that men from Bristol had already found America before Cabot did. The ‘Island of Brasil’ was a mythical place unrelated to what we know as Brazil.]

Since your Lordship wants information relating to the first voyage, here is what happened: he went with one ship, his crew confused him, he was short of supplies and ran into bad weather, and he decided to turn back.

Magnificent Lord, as to other things pertaining to the case, I would like to serve your Lordship if I were not prevented in doing so by occupations of great importance relating to shipments and deeds for England which must be attended to at once and which keep me from serving you: but rest assured, Magnificent Lord, of my desire and natural intention to serve you, and when I find myself in other circumstances and more at leisure, I will take pains to do so; and when I get news from England about the matters referred to above—for I am sure that everything has to come to my knowledge—I will inform your Lordship of all that would not be prejudicial to the King my master…

Henry VII himself referred to Cabot’s place of arrival as the “new founde land”, and ever since it has been associated with Newfoundland in Canada, partly on the basis of what little detail that Day/Say provides – although in truth the precise part of North America where Cabot landed is a mystery. Another mystery is his third voyage. With the king’s blessing (and funding), Cabot went west again in May 1498 with a small fleet – but whether he arrived in America (and possibly even settled there) or survived to return is not known for certain. (Meanwhile John’s son Sebastian became a notable explorer in his own right.) Ruddock’s own research found possible evidence that John did make it back, but she died in 2005 and her papers were destroyed. Research continues!

Funny!

America was discovered c.1200 BC by Greek Vikingar sailing from Crete during time of Trojan Wars

America colonized prior to 400 BC, as written in Hermocrates Dialogue by Plato (Atlantis)

America re-planted Tree of Life from Mesopotamia to MesoAmerica, called it the 'Religion of Thor'

American Vikingr created Youcantan Indians, fallen Leifr Eiriksons (call him Leaf 'chief' of the Tree)

Vikings returned to Europe in 791 AD to stave off Christianity, lost a sea battle before reaching land

Scandinavian Vikings (Heathens as mentioned in letter) returned to America 985 AD, attacked

Federated States of America 1040 AD militarized Indians, end of Viking Era

Confederate States of America 1255 AD, end of Templar Era 1307 AD in Europe