The last pilgrim, 1538

So many capons! And let's hope she liked fish.

Two weeks ago, we looked at five eyewitness accounts of the martyrdom of Thomas Becket in December 1170. Stories of miracles (alleged to have occurred in his lifetime and after it) proliferated rapidly, and he was fast-tracked to canonisation as St Thomas of Canterbury as soon as February 1173. His relics quickly became a key site for pilgrims, and on the first jubilee of his death, in 1220, a grand new shrine was built.

While historian John Hudson might have dubbed Becket the “master of the soundbite” in 2006, for 300 years he was honoured and venerated like no other. Of course, Geoffrey Chaucer immortalised the concept of making a pilgrimage from London to Becket’s shrine in his Canterbury Tales (written in the 1380s/90s), and people still make the journey in one way or another today. (I’ve just done it myself, in my own odd way, and I’ve written about it here.)

There aren’t many clear accounts by actual pilgrims to Canterbury, alas. Many of them would have been illiterate, and in any case this was an era when it was not exactly standard behaviour to narrate one’s life in the way we do today. Chaucer’s Tales mostly focus on the stories of his travellers, and the interactions between them, let alone the fact that he only wrote about a quarter of the stories he said he was going to. Medieval account books have helped provide information about the routes pilgrims took and how they travelled.

Actually, there is another fictional source which does help – around 50 years or so after Chaucer was writing, an anonymous supplementary manuscript appeared, presenting The Tale of Beryn, an adaptation of an old French story. Like the Tales, it had a Prologue, and this imagines Chaucer’s pilgrims arriving at Canterbury and taking lodgings. They fast overnight and then arrive at the cathedral, where a monk sprinkles them with holy water. Then they head for the shrine:

[They] kneeled down before the shrine, and heartily here besides

They prayed to St Thomas, in such manner as they knew.

And so the holy relics each man with his mouth

Kissed, as a goodly monk the names told and taught.

And then they went to the other holy places

And were in their devotion until the services were all done,

And then they drew dinnerward, as it drew to noon.1

In the late 16th century, the antiquarian John Stow included this description of Becket’s shrine derived from earlier sources:

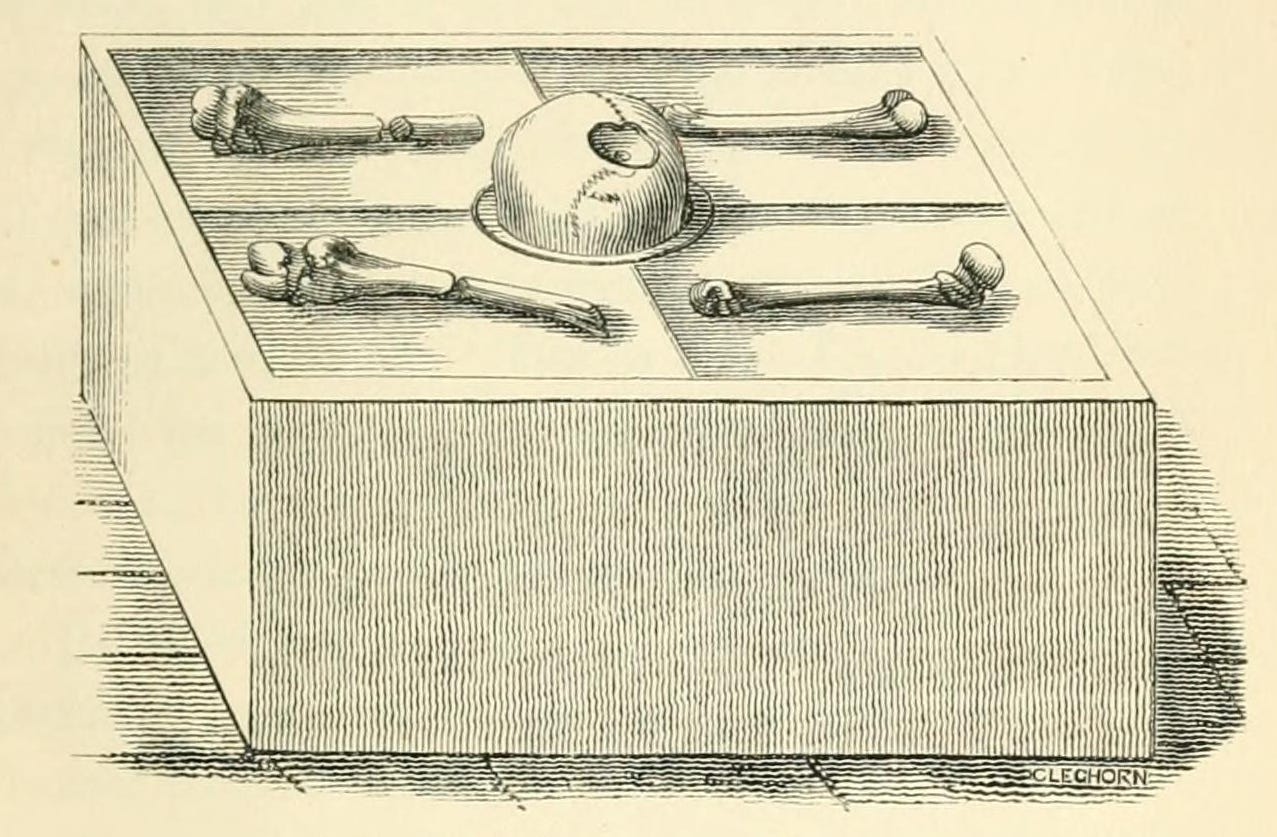

This Shrine was built about a man’s height, all of stone; then upward of timber, plain; within the which was a chest of iron, containing the bones of Thomas Becket, skull and all, with the wound of his death, and the piece cut out of his skull laid in the same wound… The timber-work of this shrine on the outside was covered with plates of gold, damasked with gold wire, which ground of gold was again covered with jewels of gold, as rings 10 or 12 cramped together with gold wire into the said ground of gold, many of those rings having stones in them, brooches, images, angels, precious stones, and great pearls, &c.

(An inventory dating from 1315 lists more than 400 jewels adorning relics in the cathedral, so they were no doubt glad of their lunch after gawping at all of this.)

We also know that the Dutch theologian Erasmus visited Canterbury in around 1513 with his friend John Colet, Dean of St Paul’s Cathedral in London, and they were given a private tour of the cathedral. Around 10 years later, Erasmus wrote a satirical account of the trip in the form of a fictional dialogue. He sets the scene:

… the church dedicated to Saint Thomas erects itself to heaven with such majesty that even from a distance it strikes religious awe into the beholders…

He goes on to describe the “vast assemblage of gold and silver” and that the exhibition of relics (not just of St Tom, and many of which visitors were expected to kiss) “seemed likely to last forever”. And he snarks at the “zeal of the showman” taking them around.

The sword that sliced part of the saint’s head off (see my previous article) was on display, and indeed what was left of the head itself:

… we descended to the crypt… There was first exhibited the perforated skull of the martyr; the forehead is left bare to be kissed, whilst the other parts are covered with silver.

Here’s an illustration from an old text purporting to show the set-up:

And then came Henry VIII, who put an end to these pilgrimages.

On 24 April 1538, he addressed a summons to the long-dead Becket, accusing him of treason. (To paraphrase Oscar Wilde, to be banished by one Henry may be regarded as a misfortune; by two looks like carelessness.) Bizarrely, Becket was given 30 days to respond – he didn’t, which under the circumstances isn’t very surprising. On 10th June, a sentence was pronounced that his bones would be publicly burnt, and the Crown would snaffle any offerings made at the shrine.

However, in August the shrine was still there – and we know this because of the last eyewitness account of a visit to it. This is in the form of a letter from a Sir William Penison2 to Henry’s famed enforcer Thomas Cromwell,3 written on 1st September 1538.4 Below is the letter, describing the visit of a French lady to the shrine (she had previously been attending the queen of Scotland on a journey there from France). There’s not a huge amount of detail – but it’s not an unreasonable assumption that she was the last ever visitor to the shrine of Thomas Becket – certainly the last recorded one.

Right honourable and my singular good Lord,

As lowly as I can, I recommend me unto Your Lordship. Please it the same to be ascertained, that, ensuing my other letters, my Lady of Montreuil has kept her journeys; so that upon Friday last, at 6 of the clock, she, accompanied with her gentlewomen and the Ambassador of France, arrived in this town; and the Master of the Rolls, with a good number of men, went to meet her half a mile out of the town; who welcomed her in his best wise, and so accompanied her to the town, where the Mayor and the Sheriffs met with her, in saluting and welcoming her in their best way, and so accompanied, she was brought to her lodging, which she did like very well.

Upon her said arrival, the Lord Prior did present her fish of sundry sorts, wines, and fruits aplenty; the Master of the Rolls did present her torches, and perchers [large candles] of wax, a good number; fishes of sundry sorts, wines, and fruits aplenty; the Mayor and the Sheriffs for the town did present her with hippocras [a spiced wine], and other wines, plenty, with sundry kinds of fish. All the which presents she did thankfully receive, saying that she was never able to knowledge the high honour and reception she had received of the King’s Majesty, and his subjects.

And so, within two owes after, by the hands of my servant, I did receive Your Lordship’s letter, dated the 28th day of the last month, [of] which [having] seen the contents, I made her partly a counsel, touching her sojourning here, in case the King’s Majesty should not come by yesterday to Dover; she being right glad and content to follow the King’s pleasure, making a very good [appearance] in showing herself, the more she approaches the King’s Majesty, the gladder to be.

And so, yesterday ensuing, the Master of the Rolls, in the morning, did present her a plenteous dish of fresh sturgeon, and so, by ten of the clock, she, her gentlewomen, and the said Ambassador, went to the Church, where I showed her Saint Thomas’s shrine, and all such other things worthy of sight; at the which she was not little marvelled of the great riches thereof; saying [them] to be innumerable, and that if she had not seen it, all the men in the world could never have made her to believe it. Thus overlooking and viewing more than an hour, as well as the shrine, Saint Thomas’s head, being at both set cushions to kneel, and the Prior, opening Saint Thomas’s head, saying to her three times, “This is Saint Thomas’s Head”, and offered her to kiss it; but she neither kneeled, nor would kiss it, but still viewing the riches thereof.

So she departed, and went to her lodging to dinner, and, after the same, to entertain her[self] with honest pastimes. And about 4 of the clock, the Lord Prior did send her a present of coneys, capons, chickens, with diverse fruits aplenty; insomuch that she said, “What shall we do with so many capons? Let the Lord Prior come and help us to eat them, tomorrow, at dinner”; and so thanked him heartily for the said present. At night, she did sup with the Ambassador.

And thus we remain, in making of good cheer, tarrying for to know your Lordship’s further pleasure. With this, Jesu preserve Your Lordship in long life, with much honour. From Canterbury, the first day of September.

Always ready at Your Lordship’s commandment,

William Penison.

Within days of this report, the shrine had been smashed to bits, and the loot carted off. John Stow commented:

The spoil of which shrine, in gold and precious stones, filled two great chests, such as six or seven strong men could do no more then convey one of them at once out of the church.

Thereafter St Thomas could only be referred to as ‘Bishop Becket’ and his sainthood in England at least was only officially reinstated in the 18th century. Were his bones actually burnt? The jury is out on that.

(But if you’re a paid subscriber, below is a short coda to this story, about the mystery of Becket’s bones!)