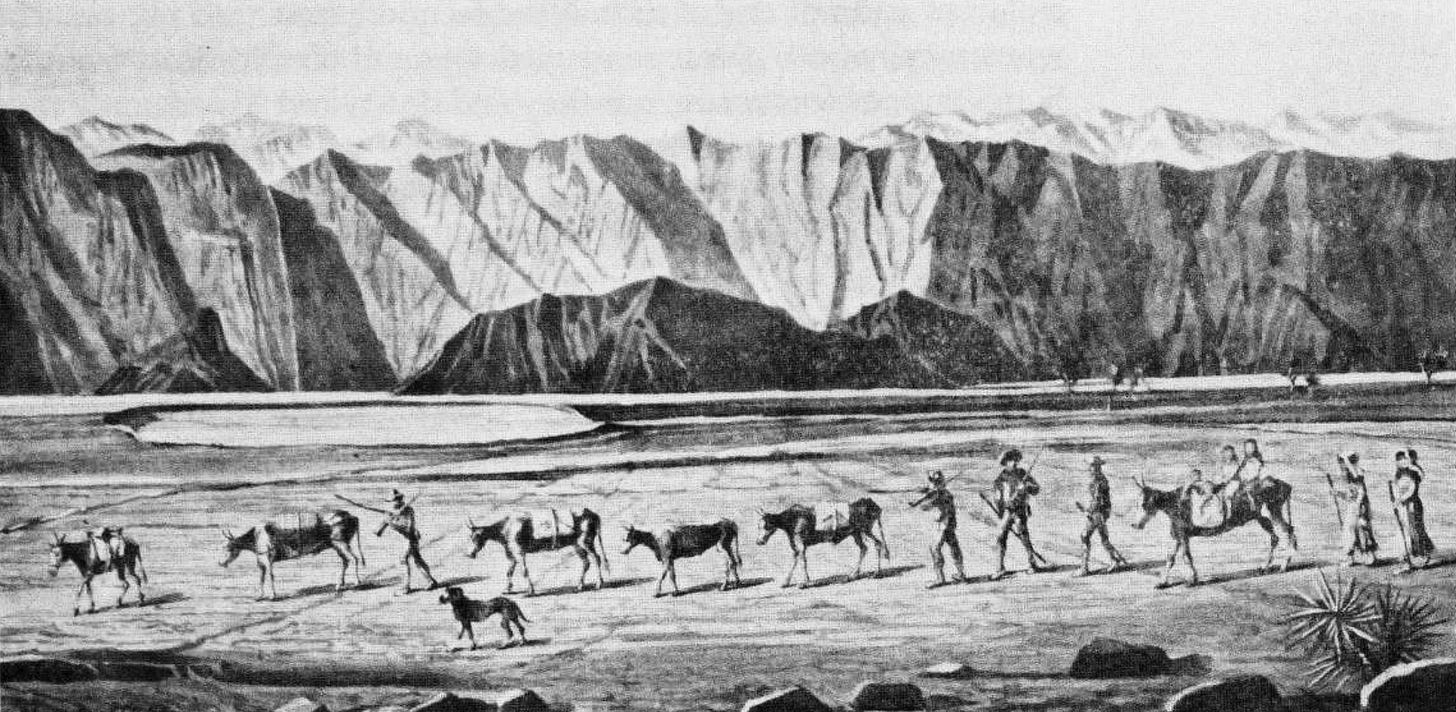

Goodbye Death Valley, 1850

And save the mule…

It’s January 1850 – 175 years ago this month – and a small group of travellers is lost in Nevada on their long journey to seek fortune in the newly discovered gold fields of California. Supplies are dwindling, the oxen are weak, there are children in the group. Things are desperate. Two fit men in their twenties are their only hope.

Those two men, William Lewis Manly and John Haney Rogers, are remembered to this day in monuments and geographic features in the harsh landscapes of the Western United States. Rogers was a man of few words, and we only have a short newspaper account giving his version of what happened, so it’s to Manly we will turn for the full story.1

Manly (also spelled Manley) was born in Vermont in 1820, then moved to Ohio as a child. After a spell in what is now Michigan, he became a hunter and trapper in Wisconsin.

In 1849, the Gold Rush exploded, and Manly joined thousands – who would become known as the ’49ers – heading for California and the riches to be expected from what the Wisconsin Tribune described as “the inexhaustible supply of gold”.

He began by heading for the Green River in Wyoming, aiming to travel by boat from there into the Colorado River and then to California. It was not to be an easy journey – some boats and many supplies were lost, and they had to carve three new dugouts from pine trees in order to keep going. They were saved by Chief Wakara of the Utah Indians (he had a complicated relationship with Brigham Young – the Mormon pioneer we’ve met before), who persuaded them to continue on land.

And so the group made it to join other gold hunters at Salt Lake City, a mustering point before the arduous crossing of the Great Basin desert and the Sierra Nevada. Only two years earlier, the Donner Party of pioneers had gone into legend for being trapped in the snow in the Sierra and having to resort to cannibalism, so the journey was not for the faint of heart. Enter Captain Jefferson Hunt, a Mormon soldier who said he could lead the prospectors safely to California. He wasn’t wrong – but a large portion of the party became impatient at the slow progress. When a hand-drawn map of a short cut came to light (there are conflicting stories about its provenance), around 100 of the 107 wagons opted to take this route instead, believing they would save 500 miles. Many were soon discouraged by a canyon on what is now the Utah–Nevada border, but 27 wagons pressed on.

Then a further split emerged. Somewhere near the Nevada salt flat of Groom Lake (now part of the US military’s infamous Area 51), two factions emerged. The Bennett-Arcan party planned to head south in search of water near the snowy peak of Mt Charleston; the Jayhawkers meanwhile wanted to continue westward. By now, it was Christmas, and two months had passed since they had left Hunt’s more cautious crew. A parched valley and the wall of the Paramint Mountains loomed ahead. The Jayhawkers abandoned their wagons, ate their weary oxen and continued on foot, finding a pass and eventually an Indian trail that led them to safety.

But the Bennett-Arcan group was struggling and couldn’t see how to cross the Paramints (which they mistakenly took to be the Sierra Nevada). Let’s let Manly take up the story.

After a long council and much argument, it was decided to send Rogers and myself to find the way and return as soon as possible, for bread now was only given to the children and the cattle must be saved as they were the only means of livelihood…

The women made us each a knapsack and put all the meat we had dried from two oxen in them. You can believe me, when I tell you that the oxen had not a speck of fat on them… They gave us a little tea and a few teaspoonfuls of rice to take along in case we were sick. I had a pair of buckskin leggins that I brought from Wisconsin which I wore, I also took one half of a small blanket. Rogers wore his coat and went without any blanket. We had new rawhide moccasins on our feet. Rogers took Bennett's double barrel shot gun, and I took his seven shooter repeating rifle. We had each a canteen made of two one pound powder cans put together and covered with cloth.

They gave us all the money they had in camp, about $60 in all, with the instructions to bring them something to eat and some animals if we could find any. They said they would wait for us eighteen days and if we did not get back in that time, they would conclude we had perished in the snow or the Indians had killed us.

We were about ready to start, when Capt. Culverwell, who was a sea-faring man, said he would tell us how to find our way back, if we should get lost…

Our whole party [about 16 people] stood and watched us till we disappeared up the canyon out of sight.

The two men soon realised the daunting nature of their journey, with cold, uncomfortable nights and “rough country” between them and the distant snow-clad peaks of the Sierra Nevada, aware “we would not be able to return in eighteen days”. They could appreciate the beauty, too, though:

The high mountain glittering and gleaming in the morning sunlight and the lesser peaks clothed in dazzling crystal was the grandest and sublimest sight we had ever seen.

Our task now before us looked very hard for two lone men to accomplish. Language is inadequate to express any one’s feelings without realizing our situation or without some realistic comparison… Maybe we all might starve, who could tell from the situation as we now saw it? … we weighed the matter to the best of our ability and came to the conclusion that there was no other course for us to pursue than to go ahead live or die.

And so they pressed on, desperately hungry and thirsty:

… we watched to gather every green spear of grass that might grow on the north side of a rock, to eat and quench our thirst. We had carried bullets and small stones in our mouth all day, and had kept from talking as much as possible. We traveled with our mouths closed to keep from wanting water. We were now unable to eat, though very hungry.

Eventually they encountered another camp of travellers, some of the Jayhawkers, which saved them, but they needed to press on and bade their farewells again. Manly injured his leg, but Rogers insisted “We will either die or go together”. They made themselves new moccasins from calf’s leather, and finally hobbled their way into Rancho San Francisco in the San Fernando Valley. They had walked more than 250 miles in just 11 days.

At the end of January 1850, they set off on the return journey, now with supplies and two horses to ride, plus a mare and a raggedy one-eyed mule to take back to the group. The mare died on the way, and the other two horses were unable to continue (“our mule proved to be the smartest of them all”), so they had to finish the journey on foot again. Here’s the touching description of the mule’s big leap to survival:2

The last horses we had bought we had intended for the women and children to ride on and now they were gone. I thought the women and children could not walk where we had and their bones would be left to bleach on the desert. This prospect caused us to feel bad and we almost gave up in despair…

How to save our mule was a puzzle. Finally, we decided on the only plan we could study out. We concluded to take the mule down the canyon a ways and help it climb up the steep rocky mountain side as far as we could. We tried to fix the way for it as best we could by throwing loose rocks into the canyon, so the mule could have something solid to stand on. We succeeded in getting her, by a great deal of hard work, up to near the head of the falls… The rocks there were as smooth as if they had been washed by water and sloped down directly to the head of the fall. Now if our mule made a misstep here it would fall fifty feet to the bottom of the canyon, which would be sure death. I had the long pack rope around the mule and went ahead fixing the way as best I could and paying out the rope; I climbed across this smooth dangerous place, while the mule looked every way for a way out, but there was none. It could not turn around and there was no way for it only to try and cross this bad place, and the mule would have to take two jumps to do it.

“Now,” Rogers said, “you pull on the rope and call her and I will take these big rocks in each hand and yell at the top of my voice, and make her think I am going to kill her.” … Rogers’ powerful voice echoed throughout the canyon, and thus the fearful venture began. The mule made one big jump and struck the smooth slanting rock about half way over; as she was not shod she did not slip and the next jump landed her safe above the falls…

“I have tried to forget the trying past of this trip ever since 1849 and have refused talking about it,” Manly wrote, though of course here he was telling his story after all. The full account is a great read – and 26 days after they had left the Bennett-Arcan group, they returned to save the day, the mule still with them.

On their approach, they encountered the body of Captain Culverwell (who had set out to look for them a couple of weeks earlier), and feared the worst – but astonishingly the rest of the group had all survived, and Manly describes the touching reunion:

They, including Mrs. Bennett, came running to meet us, and here the pen of no man like myself can describe the scene. They were so overjoyed that they could not talk, but all eyes were moist and silence reigned for some time. Mrs. Bennett fell before me on her knees and clasped her hands around my lower limbs and wept, as we all stood with our tongues tied and holding each other by the hand.

Armed with their new knowledge of the route back to the San Fernando Valley, Manly and Rogers led the group safely back to Rancho San Francisco, where the party finally arrived in early March. Let’s visit one last important scene, though, as the party pauses on the way out of the desert:

We stood here and talked a few minutes, and Bennett took off his hat, and Arcan and I did the same and said, “Goodbye Death Valley,” and that locality has ever since borne the name.

It all worked out for Manly – he found his gold, went back to Wisconsin by steamboat and then returned to the gold fields again from 1851 to 1859, making enough money to set up a farm near San Jose, get married and live out his life. He died in California in 1903. Rogers, too, settled in California and lived until 1906.

A note on the source text. Manly kept contemporary notes of the events, but they were later lost or destroyed, and it was nearly 40 years later that he came to tell the story again from memory, so perhaps we must make allowances for that – although he also took pains to check his story with others there at the time. His book Death Valley in ’49 was published in 1894 and tells his full life story, with the help of a ghostwriter. However, he also contributed a series of articles to The Santa Clara Valley newspaper in 1888, and it’s these I have used as a more primary source. The key articles are collected along with loads of other good material in Leroy & Jean Johnson’s 1987 book Escape from Death Valley.

Every Hollywood screenwriter knows the ‘Save the cat!’ storytelling method, but I like to think Manly’s ‘Save the mule!’ got there first. In Manly’s 1894 book, the mule story gets extended to three whole pages. “I thought a great deal of my fat little one-eyed mule,” he adds much later.

Great, swashbuckling stuff! Very nicely told, thank you.

What a terrific story of overcoming - thanks for sharing it with us all!