A trip with Mrs Sillery, 1858

A fare-dodging adventure in Louisiana

Last week we met Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon, an early British feminist who campaigned for women’s rights and for the abolition of slavery, and read her eyewitness account of a slave auction in New Orleans. Much of her American trip of 1857–8, a sort-of-honeymoon with her French physician husband Eugène Bodichon which enabled them to survey society in the United States, just a few years before the American Civil War.

Barbara’s diary1 of the trip (aided by her keen eye as an artist) details many of the encounters they had, often in the tragic arena of slavery – but as she acknowledges in the extract I share with you this week, there were moments of comedy on her travels too. I was tempted to cover her meeting with the legendary pioneering women’s rights and anti-slavery campaigner Lucretia Mott – whom Barbara described thus…

She looks just like a picture. I never saw such beautiful old lady, really beautiful and so exquisite in her dress, like a pearl. I fell in love with her immediately. She looks ‘full of grace’ in every sense of the word. I do not wonder her preaching has stirred so many souls, her aspect is eloquent, her smile full of good things. She seems to be full of vigour and looks in perfect health, though I believe she is seventy years old. [Actually she was 65.]

– but somehow a train journey in the company of the entirely un-famous Mrs Ellen Sillery was more enjoyable. So here it is.

27th December 1857

[Barbara has described the rooms they have taken in a house in New Orleans and their fellow “inmates”, including “Mr. and Mrs. Sillery (he is a ruined Englishman, she a merry American who makes dresses)”…]

Mrs. Sillery is a character. She was rich once, but takes work and poverty kindly. She is one of those women who have no sensibility – lots of kindness, cheerfulness, but no nerves or imagination. She chose to stay in ’53 here when the yellow fever was awfully raging [between 7,000 and 10,000 people died in New Orleans in this epidemic]. She nursed seven people who had it and saw every day bodies burnt in the streets by the dozen and never felt afraid. She says death makes no impression on her. “I know my husband will die (he is consumptive), but I don’t care… I felt my sister’s death very much,” and yet she cut off all her hair and wears it at evening parties on her head in grand plaits!

She has taken a great fancy to me and asks me to go to see her mother’s plantation for few days’ visit if “will so far humiliate myself.” Whether they know you or not, the Americans are always hospitable. It is enough if you are a stranger.

3rd January 1858

Look on the map and you will see a railway goes straight north to Vicksburg on the Mississippi, that they call the Jackson line. Mrs. Sillery (the wife of the sick Englishman) said to me yesterday, “Go with me up the Jackson line tomorrow.”

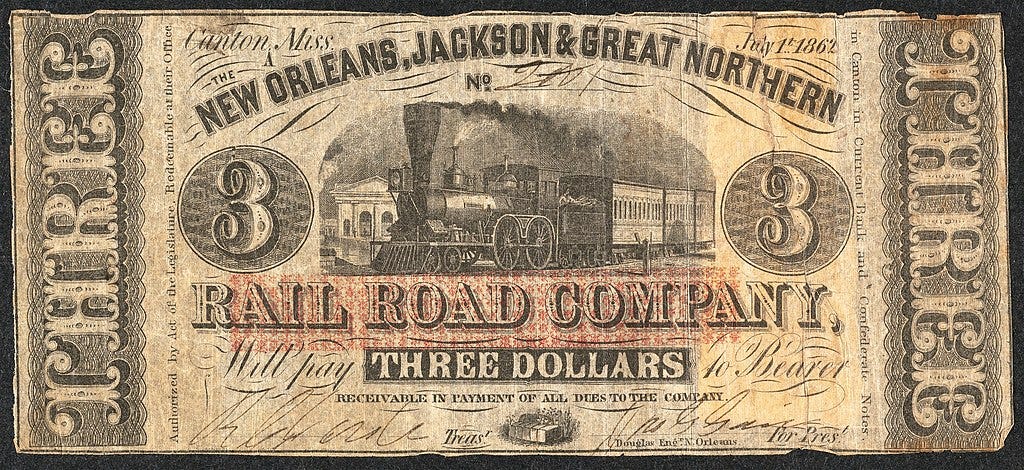

[Begun in 1852 and completed by 1861, the New Orleans, Jackson and Great Northern Line spanned 206 miles from New Orleans to Canton, Mississippi, with connections there onward to Bangor, Maine and Chicago. It had opened up new areas for cotton plantation and settlement and took on stragetic importance during the Civil War, during which it was badly damaged.]

“I have no money, I can’t,” said I, but she said money did not matter. I put up my drawing things and bread and cheese, and lo and behold found myself in the wilds of Louisiana forty miles from New Orleans without paying for my ticket, and Mrs. Sillery did not pay either.

It was curious going through the cypress forests to see the cows, who had taken the railway as a dry bed, leisurely turning off into the swamp. They made us wait sometimes, for although all the American engines have an iron paw to clear the road in front, they generally stop for a cow or donkey to get out of the way.

Mrs. Sillery flirted with all the gentlemen in true Southern fashion. I looked out of the window and saw wonderful pictures: immense trees – looking like the tall oaks in Fontainbleau Forest… The lovely star-shaped leaves of the gum tree are red as roses now and looked like red flowers. The bamboo is a graceful plant in the jungle of dark vegetation. I never saw it until today here. The magnolia grows forty or fifty feet high, I should guess. Its foliage is wonderfully perfect and rich in colour – but I am so done up with the excitement of the day that I can’t write of anything but Mrs. Sillery. She amuses me very much. She is the frankest person I ever saw. She has no high ideal above herself; therefore, being satisfied, she tells you what she does and thinks in the most astounding manner. Most people, I think, are a little anxious to conceal their vices because they hope to amend. Not so with my friend at all.

She is thirty-seven. She is good-looking and in my hat looked quite attractive. I noticed a gentleman speak to her with embarrassment and I asked her why when we were in the wood. She told me he was her first lover, but one day, having a ‘flare up’ with him, she accepted a Frenchman out of spite. The day was fixed for her marriage and the Frenchman who had hated his rival went and asked him to be groomsman. Old Lover said, “Yes, if you are going to marry one of the sisters of Ellen.”

Frenchman said, “You will see,” and behold the bride was Ellen. Old Lover did all he could to prevent the marriage but in half an hour it was over, and then Ellen told the Frenchman she loved the old lover and never should love him!

He was enraged and was jealous, and as she said, “We led a cat-and-dog life for three years and then I got a divorce and my husband married my sister!” And soon after, she married Mr. Sillery. She said, “You know, I don’t love him and I should not care if he died. – If I marry again it shall be an American. I have had enough of Englishmen and Frenchmen.”

The frankness of Americans is amazing! This woman slaves at dressmaking, earns money for her husband and nurses him very kindly. Her character has a kind of superficiality which is very American. I never saw anyone like her in my life.

The conductor of the railway put us out at a log-hut station where he said we should be handsomely treated, and so we were. The station-master made a blazing fire in the stove and we made ourselves quite at home.

I sketched the forest and listened to the conversation of the four workmen who were at breakfast on venison and roasted potatoes (smelling exquisitely savoury) and drinking claret… Two of these workmen were Germans, one Italian, one American…

Mrs. Sillery said she would send them some wives from New Orleans. I said I would send some from England if they would give me an alligator. “Oh, a thousand alligators for an English wife!” said the handsome young German…

Then the station-master told of all the accidents he had known. How two conductors had been killed in four years.

I should have enjoyed their conversation much more if they had not all used such horrible language. Instead of saying, is “Here is the train,” they said, “Here is the hell train,” and the Germans never opened their mouths without a Goddamn…

We went to pay a visit to the only house, in which were two or three German families – two pretty German women, two healthy children and at least ten or twelve men. The way to the house was made from the rail by planks from tree to tree. There was no possibility of walking in the swamp. They were very glad to see us and I talked to them in French (they came from near Strasburg). They said they made money and liked the country! I should not! I never saw or imagined a more disagreeable position than to live in a house in a wood from which you could never walk a step. They said there were many large snakes and alligators by the thousand, but it was too cold that day for them to leave the mud. Would we come again and see them?

It was a strange excursion, difficult to describe, but I hope to paint a picture of a runaway slave in these woods: Tragedy. Mrs. Sillery was the comedy, and her dialogues came in as Shakespeare brings in broad fun next to deep solemn scenes. She knew almost every one in the train, having lived on the line and been born in this country and talked to each après sa manière d’être.

Only a week later, Barbara would write of “poor Mrs. Sillery”. Her husband, ill with tuberculosis, also “was mad or wicked or both, beat her, and threatened her with a loaded pistol”. She resorted to hiding from him “shaking with fear” and Barbara advised that she could get a divorce (a right for women that Barbara had campaigned for back in England) – but Mrs S. went to see a fortune teller instead. A doctor meanwhile suggested that Mr Sillery was “not a man to die” after all, and that’s the last we hear. (I’ve combed genealogy databases but not managed to learn more of the pair.)

An American Diary, 1857–8, edited by J.W.Reed, Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1972.