A great deal of steam! The pudding was out of the copper. A smell like a washing-day!1 … In half a minute Mrs. Cratchit entered – flushed, but smiling proudly – with the pudding, like a speckled cannon-ball, so hard and firm, blazing in half of half-a-quartern of ignited brandy, and bedight with Christmas holly stuck into the top.

Charles Dickens, A Christmas Carol, 1843

Histories is a couple of days early this week as I’d like to do a Christmas special before returning to the final part of the history of hotels in my next piece. My Christmas childhood memories always involved a Christmas pudding,2 lit on fire with brandy, and with a silver sixpence hidden inside it, so what better subject to delve into the history of?

Long before it was a sweet pudding, the ancestor of Christmas pudding was a spiced porridge served during winter feasts. In medieval England, grand holiday banquets often began with a thick pottage – a stew-like mixture of meat and grains – enlivened with expensive spices and dried fruits saved for special occasions. One early version was known as frumenty, a boiled grain pudding sometimes enriched with eggs, almonds, currants or wine. The idea of combining meat with sweet ingredients might seem a bit strange to modern palates,3 but in the Middle Ages the line between sweet and savoury was a lot more blurry. A 15th-century Christmas dish could easily mix beef, spices, bread and raisins into one massive stew.

By the 1500s, such festive broths had earned the nickname ‘plum pottage’ or ‘plum porridge’ – ‘plum’ in older English meaning any dried fruit (usually raisins) rather than fresh plums. The first record of plum pottage comes from 1573,4 defining it as “pottage made thick with meat or crummes of bread” – it was a meat-based broth bulked out with bread and fortified with dried fruits and spices.

For medieval and early modern celebrants, this plum porridge was typically served as a first course on Christmas Day or Twelfth Night. The ingredients for the dish were not cheap, and so the provision of a pudding by the lord of the manor to his tenants, or a master to his servants became a traditional way of demonstrating their munificence. This is clearly described (along with a stern instruction not to get drunk!) in the carol ‘All You That Are Good Fellows’ first recorded in the chapbook Good and true, fresh and new, Christmas Carols printed in 1642, by “E. P. for Francis Coles, dwelling in the Old Bailey”:

All you that are good fellows,

Come hearken to my song;

I know you do not hate good cheer,

Nor liquor that is strong.

I hope there is none here

But soon will take my part,

Seeing my master and my dame

Say welcome with their heart.This is a time of joyfulness

And merry time of year,

When as the rich with plenty stor’d

Do make the poor good cheer.

Plum porridge, roast beef, and mince pies

Stand smoking on the board,

With other brave varieties

Our master doth afford.5

Only five short years later things took a turn for the worse in England as far as Christmas was concerned. On Tuesday 8 June 1647, the Long Parliament (Lords and Commons) issued ‘An Ordinance for Abolishing of Festivals’ – a parliamentary measure made without royal assent during the Civil War period. Now this wasn’t exactly, as you may have been told, ‘Cromwell banning Christmas’. Church Christmas services were banned, as were other forms of public celebration, but private celebration persisted in some places, though these were discouraged and sometimes policed. This didn’t stop the opponents of puritanism claiming that the dear old Christmas pud was off limits as a pamphlet of 1652, The Vindication of Christmas, details:

The Puritanical party did their utmost to “keep Christmas Day out of England,” as Taylor, the water-poet, quaintly expressed it. Their efforts were unattended with success, so far as the rural districts were concerned. He brings forward old Father Christmas, who informs us that certain “hot, zealous brethren were of opinion, that from the 24th of December at night, till the 7th of January following, plum pottage was mere Popery, that a collar of brawn was an abomination, that roast beef was anti-christian, that mince pies were relics of the Woman of Babylon, and a goose, a turkey, or a capon were marks of the beast.”

Christmas traditions returned with the restoration of Charles II, but it seems that they, and the provision of plumb pudding were still somewhat subdued as this 1687 pamphlet Poor Robin6 describes in a somewhat poetical manner:

Whereas an Ancient, Reverend, Late Worshipful Gentleman, formerly a great retainer to Noblemen, Knights, and Gentlemen, and much respected amongst the Honest Yeomen and wealthy Farmers of the whole Country, known by the Name or Appellation of Good-Housekeeping: hath by the sly insinuations and bewitched persuasious [sic] of an upstart Skip Jack called by his true name Pride, but by his Friends and Adorers by the name of Decency and Handsomeness: Most unjustly and unworthily hath justled, persecuted, and made to fly the said Good-Housekeeping from his Ancient Habitations, and Places of residence, together with his old friend Christmas, with his four Pages, Roast-Beef, Minc’d-Pies, Plumb-Pudding, and Furmity, who used to be his constant Attendants, but now are grown so invisible they cannot be seen by poor People, nor good Fellows as formerly they used to be. These are therefore to desire, will, and require you, if any Person can tell where this Good-Housekeeping doth reside, that he will desire him personally to appear this Christmas in Noblemens, Knights, Gentlemens, and Yeomens Houses as formerly he used to do, whereby he will gain great Cre∣dit to all the aforesaid Persons, and shall be Entertained with the Ringing of Bells, Sounding of Trumpets, Beating of Drums, and Acclamations of all Good People.

Thankfully the pud came back into fashion in the late 1600s and early 1700s as British cooks gradually transformed the old plum pottage. They reduced the meat content, bumped up the flour, suet and sugar, and began boiling the mixture in a cloth, yielding a firm, dome-shaped, pudding that could be sliced. The invention of the pudding cloth (a linen bag for boiling puddings) in the 17th century was a game-changer. No longer did one need animal guts or stomach linings7 to encase a pudding (as in a sausage or haggis). A floured cloth would do the job, freeing the pudding from dependence on an animal casing and allowing a smoother, rounder shape. With more flour and suet in the mix, the pudding became less a soup and more a cake.

By the early 18th century, recipes for plum pudding (sometimes also called ‘plum duff’ or just ‘Christmas pottage’) proliferated in cookbooks. They still often included meat fat – beef suet remained a key ingredient – but the actual meat and stock of the old porridge were usually left out. As in this recipe from the popular cookery writer Hannah Glasse (1708-1770):

Take a pound of suet cut in little pieces not too fine a pound of currants and a pound of raisins storied eight eggs half the whites half a nutmeg grated and a tea spoonful of beaten ginger a pound of flour a pint of milk beat the eggs first then half the milk beat them together and by degrees stir in the flour then the suet spice and fruit and as much milk as will mix it well together very thick. Boil it five hours.

Before I go any further I’d just like to dispel some Christmas pudding myths. It is often said that King George I was ‘The Pudding King’. The story claims that King George I (who came from Hanover to rule Britain in 1714) loved plum pudding so much that he insisted it be served at his first English Christmas banquet, thereby ‘restoring’ it to fashion after Puritan neglect. In this telling, George I’s pudding at Christmas 1714 earned him the nickname ‘Pudding King’ and solidified the dish’s place in holiday tradition. It’s a lovely story – but unfortunately there is no contemporary evidence for it. As food historian Ivan Day uncovered, “the eighteenth century archival record is curiously silent on this matter… It is not until the twentieth century that the story surfaces”.

Then there is the oft-repeated story that the Christmas pudding ritual was established in medieval times with deep religious symbolism: supposedly, the pudding should be made with 13 ingredients to represent Christ and the twelve apostles, While again lovely, this story is entirely unsubstantiated. There is no evidence in medieval or Renaissance records of such a specific practice. Food historians believe this ‘just-so’ story was a later invention – likely Victorian or early 20th-century in origin – projecting Christian symbolism onto an older folk practice.

During the Georgian era, Britons fancied that plum pudding, along with roast beef, was a national dish unique to England (contrasted with the “frogs and ragouts” of the French). This pride appears in popular culture and satire. In 1805, caricaturist James Gillray published a famous cartoon, The Plumb-Pudding in Danger, depicting British Prime Minister William Pitt and Napoleon Bonaparte carving up a globe-shaped plum pudding that represents the world:

By 1800, the transformation from medieval porridge to pudding was complete. Food writer John Mollard, in The Art of Cookery (1801), even introduced candied citrus peel into the dish – an ingredient unknown to earlier versions,8 but indicative of the growing range of imported sweet ingredients available. As techniques of meat preservation improved, people felt less need to eat meat in their holiday puddings, and more inclination to steadily increase the sweet elements (dried fruits, sugar, spices). What had once been a beef stew with hints of fruit evolved into a rich fruitcake-like batter barely held together by flour and eggs.

In the early 19th century, ‘plum pudding’ truly became ‘Christmas pudding’. It was in the 1830s and 1840s – the reign of Victoria – that the plum pudding was firmly fixed as the traditional end to a Christmas dinner. The English celebration of Christmas itself was undergoing a revival and reinvention, with Victorians enthusiastically embracing decorations, carols, gift-giving, and family feasts. In this festive renaissance, the plum pudding took centre stage. The first published use of the name ‘Christmas pudding’9 is often credited to Eliza Acton, who included a recipe by that title in her cookbook Modern Cookery for Private Families (1845):

Mix very thoroughly one pound of finely-grated bread with the same quantity of flour, two pounds of raisins stoned, two of currants, two of suet minced small, one of sugar, half a pound of candied peel, one nutmeg, half an ounce of mixed spice, and the grated rinds of two lemons; mix the whole with sixteen eggs10 well beaten and strained, and add four glasses of brandy. These proportions will make three puddings of good size, each of which should be boiled six hours.

By the late 19th century, the customary day to mix the pudding was ‘Stir-up Sunday’, the last Sunday before Advent. This little ritual was prompted by a pun on the Anglican prayer for that day, which begins “Stir up, we beseech thee, O Lord, the wills of thy faithful people…”. Parishioners joked that it was a divine reminder to ‘stir up’ the Christmas pudding in time for it to mature by December 25th. The whole family took turns stirring the bowl, traditionally stirring east to west in honour of the Magi’s journey, and each member would make a secret wish during their stir.11

Another Victorian custom was the inclusion of tokens or charms in the pudding. In earlier times, a coin had sometimes been baked into Twelfth Night cakes as a token of luck. This morphed into the Christmas pudding tradition of hiding a silver sixpence in the mixture for one lucky diner to find. Queen Victoria herself reportedly added sovereign coins12 to her puddings as a thank-you gift to her servants. Finding the sixpence, as I longed to do as a child, meant you’d enjoy wealth and good fortune in the coming year. Other trinkets like tiny brass charms (a thimble, a ring, an anchor, etc.) were sometimes included, each said to predict the finder’s fate (spinsterhood, marriage, travel and so on).13

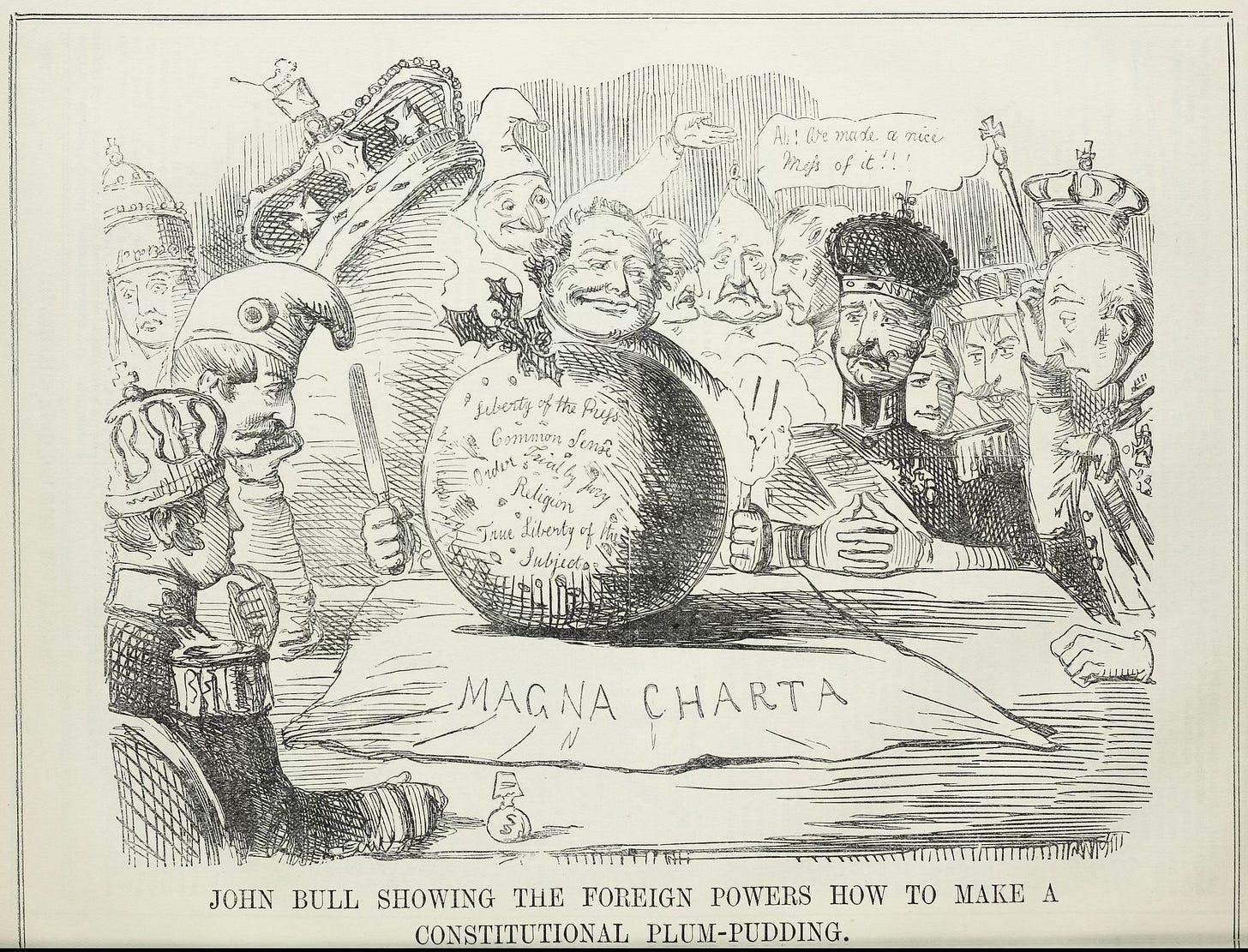

The symbolism of Christmas pudding as being an inherent part of the British soul was sometimes made explicit in popular media. An 1848 political cartoon in Punch magazine titled John Bull Showing the Foreign Powers How to Make a Constitutional Plum-Pudding encapsulated the Victorian pride in the pudding. It depicted John Bull (the personification of Britain) confidently surveying a huge plum pudding labeled with British ideals – “Liberty of the Press, “Trial by Jury”, “Common Sense”, “Order” – essentially cooking up a recipe for a free, orderly society. Meanwhile, figures representing other nations look on, presumably to learn the secret.

Alas this noble pud faced significant challenges in the 20th century as rationing during the two World Wars made it difficult for households to acquire the ingredients needed to make this cherished dish. One 1917 recipe proposed this, far from enticing, ingredient list:

1 lb stale War Bread14 bread, torn small, hard crust removed

4 oz suet

8 oz mixed dried fruit (or raisins + sultanas)

8 oz grated raw carrot

1 pint cold tea (or tea + milk mixed)

1 egg, beaten

4 oz sugar

1 tsp mixed spice

You might think that such denuded puddings may have dented my countryfolk’s resolve. But no. No! As Britain faced its darkest hour under the onslaught of Nazi Germany, the very act of having some kind of pudding on December 25th – no matter how small or ersatz – was a morale booster, a symbol that Christmas endures. Wartime diaries and letters frequently mention efforts to secure a bit of pudding for the day, a touchstone for the very way of life that was under threat. One 1940 newspaper encouraged readers: “No eggs? No suet? – Try the Ministry’s ‘National Wheatmeal Pudding’ with grated carrot and a jam sauce; the old Christmas spirit is in the effort, not the ingredients”.15

As rationing eased after the war the Christmas pudding returned to its glorious self, and has remained a staple of British Yuletide celebrations, including that of my family, to this day…

I am not sure why that would be a good thing when it comes to puddings?

I appreciate that the consumption of Christmas pudding, and, indeed, the observance of Christmas itself, are not global phenomena, but it is a fond childhood memory and a fascinating story so please forgive me my self-indulgence.

Though we do of course have pork with apple, duck with plum, and tagines, but they tend to be more of the exception rather than the rule.

I am taking this from a secondary source, please treat with caution.

I am very far from being a Marxist but having a Christmas carol that basically tells the peasants that they should be grateful for the crumbs their betters dispense is somewhat jarring. I mean, could they not charge the farmers lower rents or pay their servants more?

Or to give it its full title: Poor Robins hue and cry after Good House-Keeping, or, A dialogue betwixt Good House-Keeping, Christmas, and Pride shewing how Good House-Keeping is grown out of date both in city and country, and Christmas become only a meer name and not to be found by feasting in gentlemens houses but only by red-letters in almanacks : and how the money that should go to feast the poor at Christmas is spent upon the maintenance of Pride, with how many trades are maintained by Pride, and how many undone for want of Good House-Keeping. Which is a bit of a mouthful.

I had no idea they were bound in guts…

Probably unknown, I haven’t delved much here to be honest. It’s Christmas, life gets in the way sometimes I am afraid.

Probably the first, see my above excuse.

16 eggs!

It as actually hard to contemporaneously confirm this assertion. But it’s a nice story.

Allegedly. I cannot robustly confirm this, again, see above.

It doesn’t feel like the best Christmas experience finding a token that says that you are going to be a spinster for the rest of your life. Unless of course that is an outcome you are happy with, but given the morals and culture at the time one can’t help but that think that the discoverer of this “treat'“ would have been mercilessly teased for the rest of the day. Or, indeed, much longer.

At that time it contained only 81% flour and was grey, mushy, and generally a whole heap of no fun.

While I am in awe of the spirit, I am not sure that this a pudding I would want to eat.

Great read but man is British food nasty

John Milton published *On the Morning of Christ's Nativity* during the Cromwell era without suffering any issues. As just another wrinkle in the complications.