A history of… tattoos (Part 2)

I am not sure that I could stand "Tattowing the buttocks" with "with most stoical resolution" for even 15 minutes…

In my first piece on the history of tattoos I explained how, in medieval Europe, the tattoo had more or less died out under pressure from the Christian church – the expectations to this being on prisoners and on pilgrims. Elsewhere in the world, however, tattooing continued to flourish and as Europeans in general, and European sailors in particular, became exposed to these traditions the art form slowly made its way back to the continent.

Initially tattooing was still considered to be a barbarian practice. In 1519, Spanish conquistadors in Mexico City were stunned to learn of one countryman, Gonzalo Guerrero, who had assimilated into Maya society and taken on their customs. When fellow Spaniard Jerónimo de Aguilar tried to ‘rescue’ him, Guerrero refused, saying:

Brother Aguilar, I am married and have three children and the Indians look on me as a Cacique and captain in wartime — You go, and God be with you, but I have my face tattooed and my ears pierced, what would the Spaniards say should they see me in this guise?

In North America tattoos were common too. Captain John Smith (1579–1631), one of the founders of Jamestown, observed the patterns the Powhatan and other Algonquian tribes of Virginia had adorning their bodies. He wrote that the native men and women had:

…their legs, hands, breasts and faces cunningly embroidered with diverse marks, such as beasts and serpents, artificially wrought into their flesh with black spots.

Around the same time John White, an illustrator travelling with Sir Walter Raleigh, encountered similar body art on Roanoke Island in the Colony of Virginia and noted that it put him in mind of that tattoos that the ancient Picts were reported to have had (see Part 1). For many Indigenous nations in North America, tattoos were not simply adornment, but deeply spiritual and symbolic, often serving as rites of passage, markers of achievement and spiritual protections. Among the Sioux, particularly the Lakota, tattoos were believed to play a crucial role in the afterlife journey.

According to some versions of Lakota mythology, after death, the soul embarks on a journey to the ‘Many Lodges’, a realm resembling the world of the living but more abundant and peaceful. However, to enter this afterlife, the soul must present specific tattoos to an old woman named Hihankara, also known as the Owl-Maker. If the soul lacks the proper tattoos, Hihankara would deny entry, causing the spirit to be cast back to Earth to wander aimlessly as a ghost.

Sadly some European voyagers were not content simply looking at the tattoos of these locals (or recording them in drawings); they wanted to show the people back home exactly what they looked like. How did they do it? They kidnapped tattooed people and shipped them back to Europe. In 1566, after killing her husband, a group of French sailors abducted a tattooed Inuit woman and her (untattooed) child and exhibited them in a tavern in Antwerp for at least year. The English Privateer Martin Frobisher (c.1535–1594) brought three Inuit back to England in 1577, though they died shortly afterwards from illness and injury. This was not before Elizabeth I had heard of them, and to make up for her not having seen them in person,1 commissioned paintings of them. These included one of the mother, Arnaq, in which her facial tattoos can just be made out.

The group of peoples who arguably did the most to raise awareness of tattoos among the Europeans were the South-East Asians and Pacific islanders who came into contact with European explorers with increasing frequency over the course of the 16th and 17th centuries. The most famous example of this is ‘Prince Giolo’, also known as Jeoly, who originally came from Miangas, a small island in the Talaud Islands near Mindanao, Philippines. In 1690, he and his mother were captured by slave traders and brought to Mindanao. They were subsequently sold to English explorer2 William Dampier (1651–1715). Dampier described Jeoly's intricate tattoos in his journals, noting their elaborate designs and the use of a pigment made from the gum of the dammer tree:

He was painted all down the Breast, between his Shoulders behind; on his Thighs (mostly) before; and the Form of several broad Rings, or Bracelets around his Arms and Legs. I cannot liken the Drawings to any Figure of Animals, or the like; but they were very curious, full of great variety of Lines, Flourishes, Chequered-Work, &c. keeping a very graceful Proportion, and appearing very artificial, even to Wonder, especially that upon and between his Shoulder-blades […] I understood that the Painting was done in the same manner, as the Jerusalem Cross3 is made in Mens Arms, by pricking the Skin, and rubbing in a Pigment.

Dampier brought Jeoly back to England in late 1691 (his mother having died en route) and began displaying him himself, before selling him to the Blue Boar pub on Fleet Street, London, around June of 1692. Advertising fliers4 from the Blue Boar still survive:

Jeoly, as with many other foreign captives, was ill prepared to deal with European diseases and he died of smallpox in Oxford in 1693.5 It is believed that he is buried in the graveyard of St Ebbe’s Church, less than half a mile from where I am typing these words today. Or most of him rather – some of his skin was flailed and preserved for the Anatomy School of the University of Oxford.

It is from expeditions to the Pacific less than a century later that we get the word ‘tattoo’ itself – prior to that the designs tended to be described as ‘marking’ or ‘pricking’. Captain Cook (1728–1779) led three significant expeditions into the Pacific Ocean between 1768 and 1779. He wrote in his journals of July 1769 about the Polynesian practice:

Both sexes paint their Bodys, Tattow, as it is called in their Language. This is done by inlaying the Colour of Black under their skins, in such a manner as to be indelible. Some have ill-design'd figures of men, birds, or dogs; the women generally have this figure Z simply on every joint of their fingers and Toes; the men have it likewise, and both have other differant figures, such as Circles, Crescents, etc. which they have on their Arms and Legs; in short, they are so various in the application of these figures that both the quantity and Situation of them seem to depend intirely upon the humour of each individual, yet all agree in having their buttocks covered with a Deep black

The Polynesian word encountered by Cook was tatau, derived from Tahitian and Samoan languages. Tatau meant ‘to mark’ or ‘to strike repeatedly’ and was soon adopted, in a slightly modified form, into English, and thence other major European languages.6

The only reason the Cook had been able to go on the voyage in the first place is because he received a huge amount of funding from Joseph Banks (1743–1820), an aspiring naturalist backed by a vast amount of family wealth. Banks kept extensive journals from his travels – in case you were wondering about the how the buttocks got tattooed in black as mentioned above, he describes it happening in Tahiti on July 5th 1769:

This morn I saw the operation of Tattowing the buttocks performd upon a girl of about 12 years old, it provd as I have always suspected a most painfull one. It was done with a large instrument about 2 inches long containing about 30 teeth, every stroke of this hundreds of which were made in a minute drew blood. The patient bore this for about ¼ of an hour with most stoical resolution; by that time however the pain began to operate too stron[g]ly to be peacably endurd, she began to complain and soon burst out into loud lamentations and would fain have persuaded the operator to cease; she was however held down by two women who sometimes scolded, sometimes beat, and at others coaxd her. I was setting in the adjacent house with Tomio for an hour, all which time it lasted and was not finishd when I went away tho very near. This was one side only of her buttocks for the other had been done some time before. The arches upon the loins upon which they value themselves much were not yet done, the doing of which they told causd more pain than what I had seen.

Despite incredible pain that was obviously involved in the process, a number of Cook’s crew were sufficiently taken with them that they got tattoos themselves, amongst them7 most likely Sidney Parkinson, a botanical draftsman. Now you may find it written that this introduced tattooing as the naval tradition that continues to this day but that isn’t true. British and American sailors had been tattooing themselves since at least the mid-1600s, often using gunpowder. The American Mercury, March 17 1720, describes one as having:

…on one hand S. P. in blew [sic] Letters and on the other hand blew Spots, and upon one arm our Savior upon the Cross, and on the other Adam and Eve, all Suppos’d to be done in Gun powder.

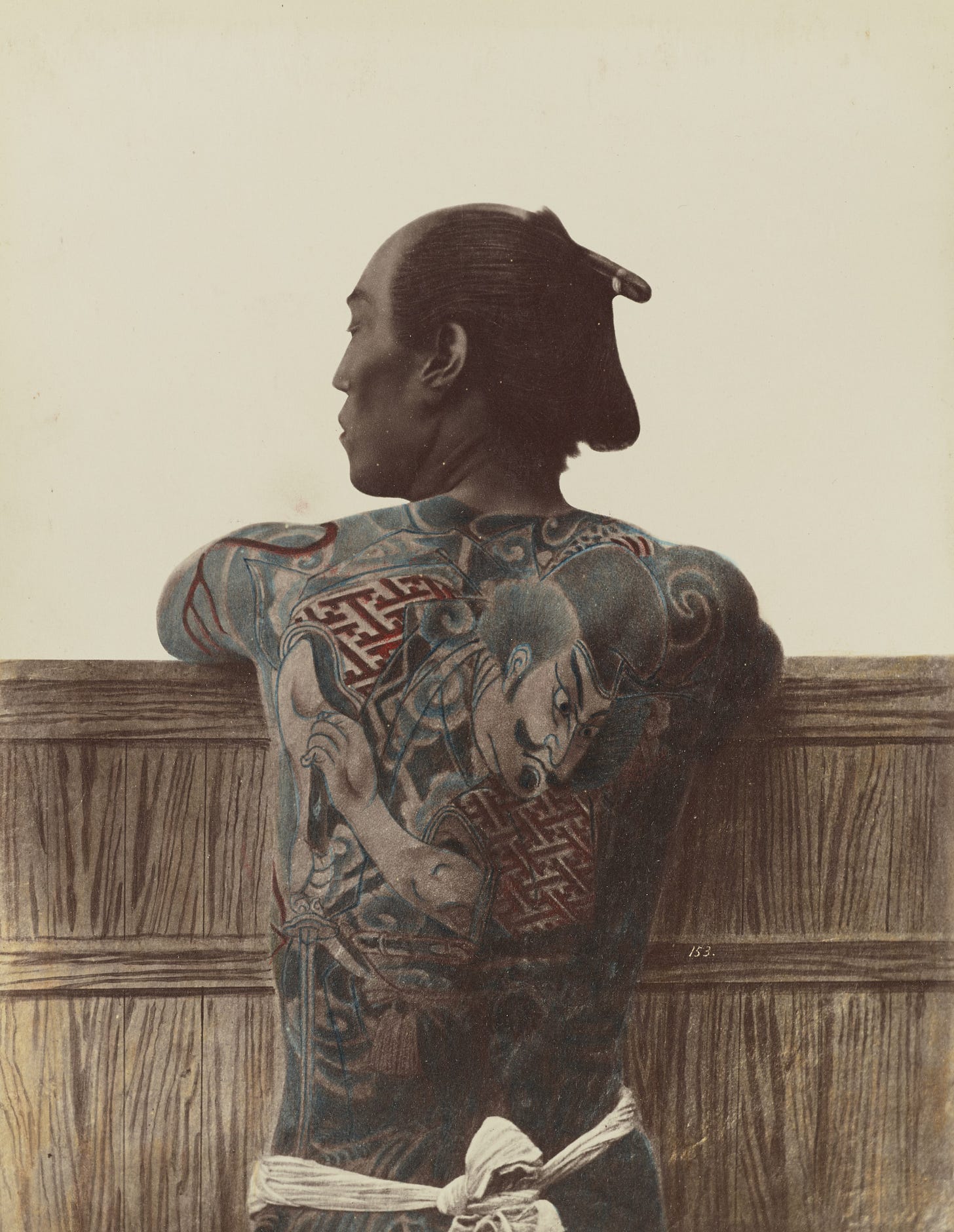

These designs were mostly simple letters, crosses, anchors and the like and it does seem that contact with the Polynesians introduced much more elaborate designs to the practice. Inspiration came from other places too. Whilst in much of China tattooing was only something that was meted out to criminals as a punishment in the south, particularly around the port city of Quanzhou it not only thrived, but became an incredibly elaborate art form. In the classic novel The Water Margin (date unknown, perhaps mid 14th century) a number of the main characters are described as having their bodies covered with tattoos of dragons and other mythical beasts. When the book was published in Japan in 1757, complete with beautiful woodblock illustrations, it sparked a craze for elaborate tattooing there. Sailors visiting these distant ports from Europe would get inked in the local styles, with the bodies becoming a visual record of their travels.

By 1800 around a third of British sailors, and a fifth of Americans, sported tattoos. Soon cottage industries sprung up in the port towns back home where former sailors who had learned their skills in Tahiti or Caton, would add to the ink collections of their comrades. But it wasn’t just sailors that they were decorating. People of ‘higher quality’ had been going under the needle for years. The earliest designs adopted by the gentry were, like initial sailors, likely very simple – hearts, initials, and in the case of women, fake beauty spots on their faces. We know that this latter practice was taking place from a passage in the Thomas Otway8 (1652–1685) play The Soldier’s Fortune (1681):

He keeps a Catalogue of the choicest Beauties about Town, illustrated with a particular Account of their Age, Shape, Proportion, Colour of Hair and Eyes, Degrees of Complexion, Gun-powder Spots, and Moles.

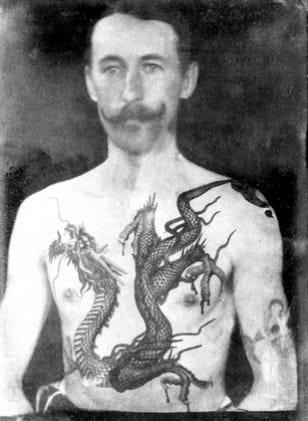

It was in the second half of the 19th century that tattoo fever took hold, driven in no small part by the fact that the classiest people of all, the royals,9 were getting them. In 1862 the Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII) got a Jerusalem cross then in 1881 the future King George V, at the tender age of 16, got a tattoo of a blue and red dragon in Yokohama. When he got married in 1893 such was the fascination with his ink that newspapers created illustrations guessing at what it might look like!

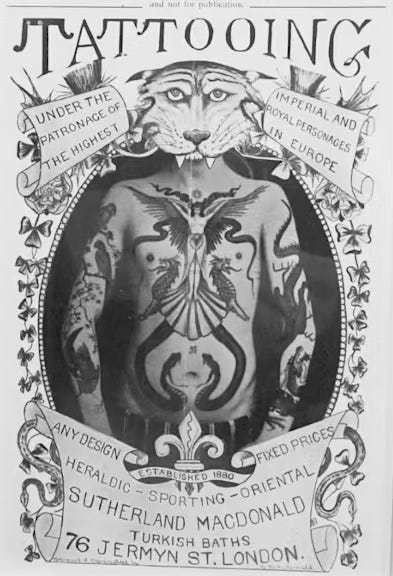

This is when one Sutherland MacDonald (1840–1942) enters the scene. Having originally set up as a tattooist in Aldershot, he opened the first public tattoo parlour in England (on Jermyn Street, London) sometime before 1894. He can reasonably be said to have been the world’s first tattooist, having coined the word. Previously the term ‘tattooer’ had been used but MacDonald considered ‘er’ ending trades as common (butcher, baker, candlestick maker etc.) where he was a professional, an artist, a tattooist.

He improved upon the electric tattooing machine patented by American Samuel O’Reilly in 1891 and he targeted a well-to-do clientele with the most astonishing designs that hold up with the best to be seen today. It was said of him that “No one in the past, and no man living to-day, can compare with Macdonald in placing really artistic pictures on the human skin” and he was described as the “Michelangelo of tattooing”.

You may think that permanent makeup, tattooed on the face, is a relatively recent thing, but no, Sutherland was doing it over a century ago, rouging the cheeks of ladies and colouring their lips. In 1898 the number of tattooed people in London was estimated at 100,000 and swiftly growing, and this craze was replicated in New York. There has clearly been an explosion in tattooing as the 20th century moved into the 21st but it seems that those getting inked today are actually behaving little differently from their ancestors from a hundred years or more earlier. While some may roll their eyes at people ‘disfiguring their bodies’ or ‘being common’, I for one would not have wanted to tell King George V that his tattoos made him ‘common’…

Some sources say that she did meet them but this seems to be a fiction.

Also pirate, privateer, naturalist.

Again, as mentioned in Part 1.

The text under the picture reads: Prince Giolo son to King of Moangis or Gitolo: lying under the Equator in the Long of 152 Deg 30 Min a fruitfull fland abounding with rich spices and other valuable commodities. This famous painted prince is the just wonder of the age, his whole body except hands, face and feet is curiously and most exquisitely Painted or stained full of variety and Invention with prodigious Art and Skill performed In so much in the ancient and noble Mistery of Painting or Staining upon Humane Bodies seems to be comprised in this one statily Piece. The Puctures & those other engraven Figures copied from him is now dispersed abroad serve only to deseribe as much as they can if sore-part of this intimitable Piece of Workmanship: The more admirable Back-parts afford us a Representation of one quarter part of the sphere upon & betwixt his shoulder whereid Arctick & Tropick Circle centre in S North Pole of his neck. And all ye other Lines Circles a Characters are done in such exact Symmetry & Proportioin, that it is astonishing & surmounts all ye has hither to be seen of this kind The Paint it self is so durable if nothing can wash it of or deface ye beauty of it. is prepared from the Juice of a certain herb or plant, peculiar to that country. wich they efteem infallible to preserve human Bodies from ye deadly poison or hurt of any venomous creature whatsoever an none but those of Royal Family are permitted to be thus painted with it. This excellent Piece has been lately seen by many persons of high quality an accurately surveyed by several learned Virtuosi an ingenious Travellers who have expressed very great satisfaction in seeing of it. This admirable person is about y age of 30, graceful and well proportioned in all his Limbs, extremely modest a civil, neat & cleanly, but his Language is not understood, neither can he speak English. Which is a bit of a mouthful.

Some sources say it was actually in late 1692.

French: tatouage (noun)

German: Tattoo (noun, borrowed directly from English)

Spanish: tatuaje (noun)

Italian: tatuaggio (noun)

Portuguese: tatuagem (noun)

Dutch: tatoeage (noun) etcetera

There is some debate about whether Banks himself got a tattoo. I think that it is fair to say that he, ahem, immersed himself very deeply in the local culture, but there is no unequivocal evidence that he got one.

He died in extreme poverty, allegedly choking to death on a piece of bread. This is despite having huge success with his play Venice Preserv’d which was a hit for centuries. On 10 April 1865, John Wilkes Booth told Louis J. Weichmann (in what is believed to be an allusion to his intention to kill Lincoln) that he was done with the stage and that the only play he wanted to present henceforth was Venice Preserv’d.

Others include: Prince Albert Victor, Tsar Nicholas II, Kaiser Wilhelm II, King Alfonso XIII, King Frederik IX, Queen Olga of Greece and Archduke Franz Ferdinand. The latter is said to have had a tattoo of a snake on his thigh “for luck”. If so, I am not entirely sure that it worked…