A history of… tattoos (Part 1)

If you bumped into someone with the words "committed licentious acts two times" tattooed on their face you could be pretty sure what they had been up to.

Some 25 years ago I got a tattoo.1 It isn’t a very good tattoo. Luckily it is on the back of my left shoulder, so most of the time I forget that it is there. I recently remembered again, and have been thinking about getting a cover-up. Naturally this then got me wondering about the history of tattoos…

It turns out that tattoos are incredibly old. Ötzi the Iceman, a Copper Age man found in the Italian Alps (d. c.3,300 BCE and who was mentioned in my very first piece on pockets) was covered with 61 tattoos. They are mostly groups of very well defined parallel lines and crosses that interestingly cluster on wear-prone joints (ankles, wrists, knees, lower back etc). While we will clearly never know for sure, it has been speculated that these tattoos were a form of therapy, perhaps akin to acupuncture, with the belief that the markings would alleviate the joint pain that inevitably accrues through use and age.2

Around the same time, 5,000 years ago, Egyptians were getting tattooed as well. Two Egyptian mummies known as Gebelein Man A and Gebelein Woman had been on display in the British Museum for decades, seemingly unremarkable (other than the fact that they were mummies) until 2017 when researchers examined them using infrared scanning technology. What this revealed was not simply geometric tattoo designs, but figures of a bull and a sheep and an intriguing ‘SSSS’ pattern. It would seem that these were more than medicinal; rather that they had a symbolic significance, particularly the bull which could have represented strength and power.

There is some evidence of even older tattooing, stretching back almost 7,000 years. This is not to be found on a mummy, but rather on the clay figure of a person made by the pre-Cucuteni culture which was found in what is today Romania.

It has even been suggested that there is evidence of tattooing on the oldest undisputed depiction of a human being – the Venus of Hohle Fels (also known as the Venus of Schelklingen) which was carved between 40,000 and 42,000 years ago. It has a series of lines incised down the arms and across the torso and chest which could be representing tattoos. Similar markings can be also seen on the arm of the the Löwenmensch figurine (also called the Lion-man of Hohlenstein-Stadel) which dates from a similar time.

Anyone who has had a tattoo in the 21st century knows that great care has to be taken, even in our relatively sterile world, to prevent the skin getting infected. Analysis of tattoos on ancient subjects has shown little or no gross scar tissue and the designs were clean and clear, so incredible attention must have been paid to hygiene during the process and aftercare – something perhaps at odds with our general perceptions about cleanliness in the Bronze Age. In the case of Ötzi it has been suggested that his tattoos were created by incising the flesh with sharpened bone or copper, forcing a mixture of herbs into the cuts then setting them on fire. This would both have created the charcoal required to pigment the designs and also acted to cauterize the wound. However these designs were executed, we can be certain that the people creating them were very skilled – there were professional tattoo artists thousands of years ago.

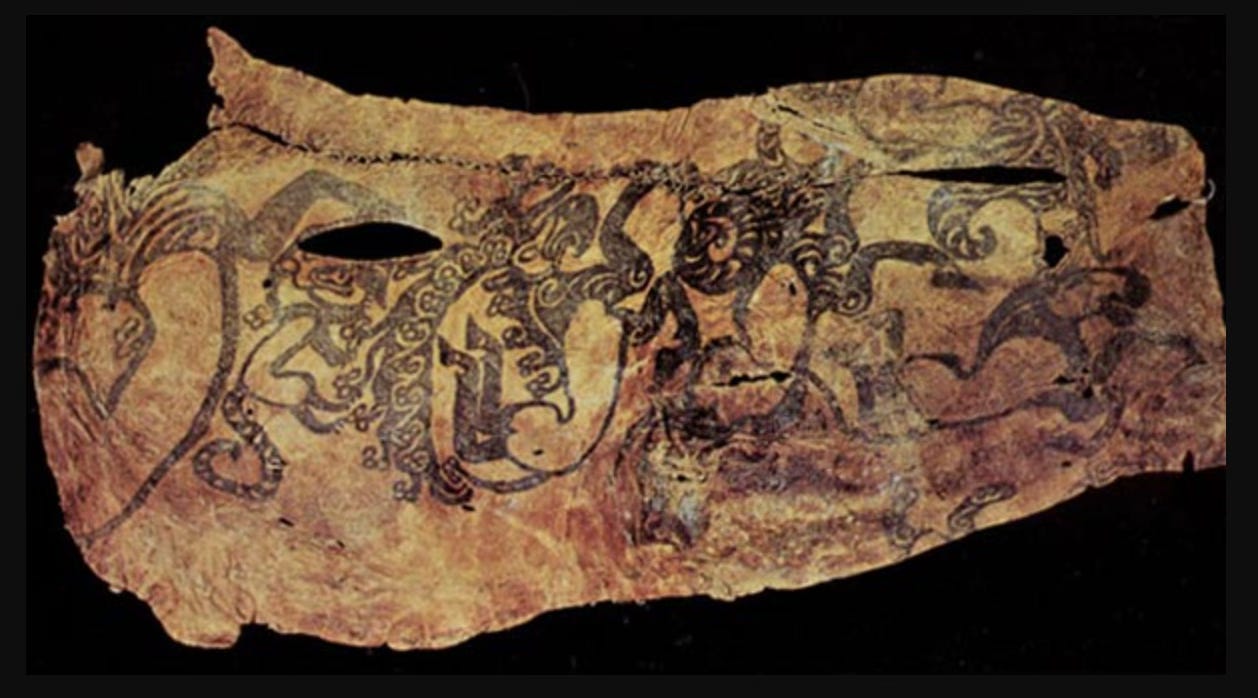

Even more elaborate designs could be found adorning the bodies of members of the Pazyryk culture who lived in central Asia between 2,600 and 2,200 years ago. Their territory extended right up into Siberia, and as a result some very well preserved bodies have been found in the permafrost. Their tattoos are astonishing – beautifully executed, stylised designs of animals winding and interlacing. As these peoples would have been well clothed at all times due to the climate, it seems that all this work was not carried out for public display; rather it held a deeper, spiritual, meaning. As one of the archaeologists who studied them commented:

They never went nude… so most of these tattoos would never have been seen by others… I think they were for magical protection. Those tattoos were probably his spiritual weapons.

Tattoos have also been found on mummies in Chile dating back some 4,000 years and on ones ranging from 2,000 to 4,000 years old in the Tarim Basin in China. Where bodies did not survive, we have further evidence of tattoos from art and literature. In the Chinese history Wei Zhi (Records of Wei), compiled around 297 CE, the passage on the Wa (仵人, early Japanese) describes how:

Men great and small, all tattoo their faces and decorate their bodies with designs. From olden times envoys who visited the Chinese Court called themselves ‘grandees.’ A son of the ruler Shao‑k’ang of Hsia, when he was enfeoffed as lord of K’uai‑chi, cut his hair and decorated his body with designs in order to avoid the attack of serpents and dragons. The Wa, who are fond of diving into the water to get fish and shells, also decorated their bodies in order to keep away large fish and waterfowl. Later, however, the designs became merely ornamental. Each chiefdom has a tattoo style—left or right side, large or small—to indicate status.

In China itself tattooing was used as a form of punishment rather than adornment. From as early as 200 BCE Mo Xing (墨刑, literally ‘ink punishment’) was employed as a form of corporal branding or tattooing, marking criminals permanently on the face or forehead with black ink or pigment. It was the lowest of the Five Punishments (五刑, wǔ xíng) in early imperial Chinese law. The tattoo usually recorded the nature of the offense, such as ‘thief’ (賊), with the aim being both public shaming and social exclusion, since the mark was visible for life. We have some specific examples from later Yuan dynasty (1279-1368) legal codes. If a couple were caught committing adultery for the first time they would be separated and receive a telling off.3 If they got caught at it a second time the man4 would be tattooed on the face with the words “committed licentious acts two times” and banished!

There is one notable exception to Chinese tattooing being the preserve of the criminals and the underclasses. According to legend,5 during the early years of the Southern Song Dynasty (1127–1279 CE), Yue Fei (岳飛, 1103–1142) returned home to say farewell to his mother before enlisting to defend the nation against the Jurchen invasion. His mother, knowing that the path ahead would test his loyalty and resolve, feared that her son might be accused of disloyalty – or waver in his service to the emperor.

To ensure he would never stray from his duty, she took a needle and ink, and tattooed four Chinese characters onto his back:

尽忠报国

‘Jìn zhōng bào guó’ – ‘Serve the country with utmost loyalty.’

The tattoo became both a symbol of his unwavering patriotism and a testament to his filial obedience – as he submitted even his body to his mother’s will. He later became one of China's most venerated generals, celebrated for his military brilliance and incorruptible devotion.6

Every inhabited continent has a long history of tattooing, from New Zealand to Polynesia to the Pacific Northwes and sub-Sarahan Africa. Given the isolation of some of these populations it is clear that this art form has been independently invented time and time again over the millennia.

Back in Europe, meanwhile, the ancient Greeks and Romans had broadly similar views on this type of body decoration. For Greeks it was an abomination, something done by barbarians (or to slaves, criminals, and prisoners of war). Plutarch’s Life of Nicias recounts that after Athens’ defeat at Syracuse, the few Athenian prisoners who didn’t die were enslaved, their status being marked with a horse7 tattoo on their foreheads. To describe the process of tattooing they used the verb stizein, to prick or sting, and the noun used to describe the result was stigma8 which obviously persists into English today. They were not, however, averse to putting them to practical use, such as in the case of Histiaeus of Miletus the late 6th–early 5th century BCE Greek tyrant who was detained at the Persian court of Darius. Herodotus tells the story:

Histiaeus, being detained at Susa by Darius, felt that he was losing his hold on Miletus. To correct this, he shaved the head of his most trusted slave, and tattooed upon his scalp the famous message: ‘When thou art come to Miletus, bid Aristagoras shave thy head, and look thereon.’ When the slave’s hair had grown again, the slave was sent secretly to Aristagoras in Miletus; upon arrival, Aristagoras shaved the slave’s head and read the message. This incited him to begin the Ionian revolt.9

The Romans would also tattoo slaves, criminals and gladiators, but additionally it played a significant role in their army. Tattoos on hands and arms were used to indicate both their status as a solider and the legion to which they belonged – somewhat akin to unit badges on uniforms today.10 Vegetius, writing in Epitoma Rei Militaris (late 4th–5th c. CE), suggested that new recruits shouldn’t be marked until after they proved themselves in training:

A recruit should not be tattooed with the pin‑pricks of the official mark as soon as selected, but first be thoroughly tested in exercise…

Writing a few centuries after the fall of the Western Roman Empire in Medicae artis principes (c. 6th CE), Aëtius explains how it was done:

First, the place where the tattoo was to be done was carefully washed with leek juice, which was known for its antiseptic properties. The tattooing ink consisted of Egyptian pine‑wood, corroded bronze and more juice from the leek.

He also handily explains how you could remove the tattoo if you were so minded:

When applying, first clean the tattoos with nitre, smear them with resin of terebinth, and bandage for five days. On the sixth, prick the tattoos with a pin, sponge away the blood, and then spread a little salt on the pricks. After an interval, apply the aforesaid prescription and cover it with a linen bandage. Leave on for five days, and on the sixth smear some of the prescription with a feather. The tattoo is removed in twenty days, without great ulceration and without a scar.11

Across the channel, in my native British Isles, the locals were very much into the tattooing game as well. Isidore of Seville writing around the year 600CE had this to say of them:

Picti a pingendo dicti, quia corpora sua ferro puncta, atramentoque per liniamenta in modum macularum pigmenta.

The Picts are so called from painting, because they puncture their skin with iron and apply pigment in patterns of spots.

It is possible that this love of body art is responsible for the name of these lands to this day. The name ‘Britain’ ultimately derives from the ancient Greek and Latin names:

Greek: Πρεττανία (Prettania) or Βρεττανία (Brettania)

Latin: Britannia

These likely came from an indigenous Celtic name – something like Pritani or Pretani – and it has been suggested that this meant ‘the painted ones’, so if you are tattooed Brit you are literally living up to your ancient name! Except this etymology is not universally accepted. It is possible the name Pretani simply referred to a tribal designation rather than their appearance. It is also possible that classical writers interpreted the name in light of their own assumptions about barbarian body art – certainly the name was in use long before Isidore of Seville used it, and he could simply have been drawing a conclusion that wasn’t true.

The fall of the Western Roman Empire and the rise of Christianity led to a marked decline in tattooing in Western Europe.12 Guided by Leviticus 19:28 – “You shall not make any cuttings in your flesh for the dead, nor tattoo any marks on you: I am the LORD” – church leaders were swift to condemn the practice as sinful, such as Clement of Alexandria who described it in the second century as “defacing the image of God”. Despite this prohibition, one form of acceptable tattooing did exist for Europeans in the Middle Ages, and that form had a deeply Christian significance.

As early as the year 500 CE Christian pilgrims in the Holy Land reportedly had crosses – or even Christ’s name – tattooed on their bodies. By the 13th and 14th centuries this practice had become common among crusaders and pilgrims alike as Swiss theologian Felix Fabri (1441–1502) describing how he received the tattoo of a cross on his right arm as a sign of his devotion.

In Part 2 I’ll explore the history of tattooing over the last five hundred or so years, including how it was ‘rediscovered’ by the Europeans. But before that I can’t help but mention that the place where Felix Fabri got his tattoo may still be in business today! Razzouk Tattoo began more than 700 years ago in Egypt tattooing Coptic Christians with small crosses on their wrists (which would enable them to gain entry to their churches). The business moved to Jerusalem around 500 years ago where it continues to this day, run by Wassim Razzouk, the 27th generation of his family to ink, making it without question the oldest tattoo parlour in the world.

It’s of a gecko. I like geckos, but in retrospect maybe not that much.

He is estimated to have been around 45 years old when he died, but had clearly lived a pretty demanding life, not least being shot with an arrow shortly before he died.

I assume that they would have had a telling off.

It is not clear if the woman would have been tattooed as well.

It is almost certainly a legend, alas.

Though he ended up being executed on false charges, only to be rehabilitated some years later.

It is not explained why a horse was chosen.

I was delighted to learn this!

This does feel like quite a time consuming way to send a message, but clearly it worked!

They could also doubtless be used to identify deserters from the army.

I am not wholly convinced that this would fail to leave a scar.

And, of course, lots of other things.

A very interesting history. Although I was impressed that you did not mention how painful some of the tattoo methods were. For instance "his tattoos were created by incising the flesh with sharpened bone or copper, forcing a mixture of herbs into the cuts then setting them on fire!!!"

Riveting! Congrats!