A history of… domestic cats (Part 1)

It was handy to have some with you if you wanted to invade ancient Egypt…

I was inspired to write this piece because of a recent BBC News story about quite how long cats have been ‘domesticated’ (anyone who lives with a cat would perhaps debate the use of that word, or else speculate that it is the cats who have domesticated us, rather than the other way around). In a nutshell, the article suggests that cats have only been domesticated for around 3,500 years but the reality is a little bit more complicated than that. This is a subject I know something about because I once wrote a book about cats and so I thought people might be interested in learning a little bit more about the ancient and medieval history of the relationship between them and humans.

The first cats are believed to have appeared a little over 30 million years ago, with the earliest known ‘true’ cat found in the fossil record being Proailurus who lived around 25 million years ago in Europe and Asia. The now extinct Proailurus was not much larger than the average domestic cat of today, weighing in at around 9kg (20 pounds), and it is believed that they were the ancestor of all of the cat species living on the Earth today.

The domestic cat is Felis catus, a member of genus Felis along with the Sand Cat, the Chinese Mountain Cat, the Black-footed Cat, the African Wildcat, the Jungle Cat and the European Wildcat, all of whom genetically diverged from a common ancestor at various times over the course of the last four million years. Some of these species are still sufficiently genetically similar that they can cross breed with each other – indeed cross-breeding with domestic cats is a significant threat to the survival of the European Wildcat.

So when did cats and humans start living together? In 2004 archeologists working on a dig site on the Mediterranean island of Cyprus found the skeletons of a cat and human buried together in a grave that was 9,500 years old. Now, you may be thinking “Well, that doesn’t prove that cats and humans were living together; someone could have simply chucked the dead cat in when they were filling in the grave?” Leaving aside the fact that that would have been a pretty odd thing to do the cat hadn’t simply been thrown into a hole. Its body had been laid out in its own tiny grave, a mere 40 cm (one and a half feet) away from the human, and it had been aligned in the same westward direction as the human body. This was a considered, deliberate act. The fact that the cat was only around eight months old also raises the (depressing for cat-lovers) possibility that the cat had been killed when its human had died so that the two could be laid to rest together.

Then there is the fact that cats are not native to Cyprus – they would have to have been brought there by humans on boats. Could some cats have snuck aboard a boat, unnoticed? That seems pretty unlikely – 9,500 years ago boats were dug-out canoes or small vessels of woven reeds so there wouldn’t have been much space for a cat to conceal itself for the duration of the voyage. This ancient grave cat was not a domestic cat as we would know it; rather it was a tamed African wildcat. Nonetheless it can lay claim to the oldest known house cat.

We can be pretty sure then that cats (albeit not the species we know today as the domestic cat) and humans have been living together for the best part of 10,000 years – possibly much longer. Dogs, on the other hand, have definitely been living with humans for more than 14,000 years, and possibly as long as 36,000 years. (In case you were wondering, goats, pigs, sheep and cattle are believed to have been domesticated 10–11,000 years ago; horses 5,500 years ago). As we mentioned earlier, there is still something weird about the domestication of cats. Most of the other animals we have domesticated already lived in either packs or herds. Pack animals have dominance hierarchies with obvious leaders. Put simply, if a human can supplant the alpha dog then the other dogs will follow them. Pack animals were already used to living in large groups, their migrations mostly driven by the hunt for fresh grazing. If you provide them with sufficient food then you can corral and control them fairly easily.

Cats are very different beasts. They are primarily solitary hunters who come together to mate. As anyone with an outdoor cat knows they are very territorial and will challenge any other puss who wanders onto their home turf. It is highly unlikely that ancient humans caught and trained cats to be useful companions. What seems most likely, as we suggested at the beginning, is that as humans developed agriculture and established settlements, and (most importantly) grain stores, so they also created the ideal conditions for mice to live and thrive. The first ‘domestic’ cats would have hung around the edges of those early villages and towns, preying on mice, rats, and other vermin. Initially they would have been wary of humans. We know that today’s European wildcats, even if raised by humans from kittens, are both nervous of, and aggressive towards, people. Then evolution would have kicked into play. If a random genetic mutation arose that made a cat less fearful of humans then the beasts that possessed it would likely have a better chance of survival than those who didn’t. Why? Well they would have hung around the grain stores for longer, continuing to hunt, while others had fled at the approach of the villagers. They would have started venturing into houses to hunt down the rodents that lived there, and also been able to feast upon discarded scraps. They would have been better able to find warmth and shelter during storms and winter months.

There is good evidence to suggest that domestic cats have evolved to like (well, perhaps not always ‘like’ – let’s say ‘tolerate’) human company. If you cross breed a European wildcat (who, as mentioned above, really don’t like humans) with a domestic cat then the resulting offspring will be much more relaxed around people. Our ancestors would have readily seen the benefit in having these furry creatures wandering around, though perhaps they saw more in cats than simply their utility. Put simply, cats just look cute to us, and probably always have. To be more specific, cats have flat faces with little snubby noses, large eyes, a high forehead, all very similar to something we have evolved to find super-cute: a human baby.

The ancient Egyptians are, of course, famous for their worship and veneration of cats. The earliest evidence of this relationship dates from the First Dynasty of Egypt almost 5,000 years ago when the cat-headed goddess Mafdet was worshiped. Mafdet was known for protecting the pharaohs against poisonous animals such as snakes and scorpions, a role that real-life cats would most likely have performed. She was also reputed to tear the hearts out of criminals and drop them at the feet of pharaoh, much as a cat will present a dead mouse to their human today.

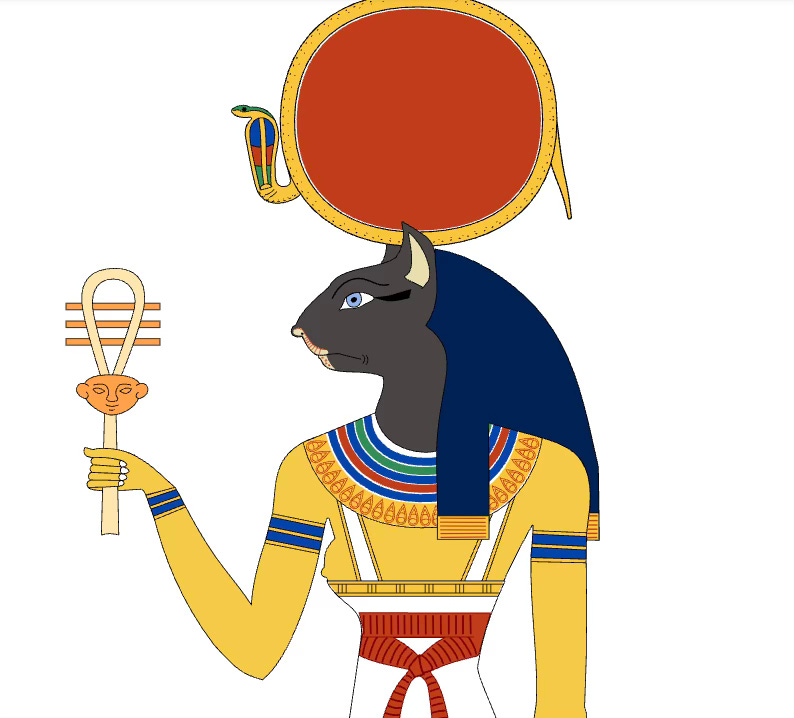

Mafdet was not the only cat-related god in the Egyptian pantheon. She was followed by Bastet (better known in the West as Bast). Originally Bast was a fierce lion-headed, warrior, goddess but over the course of a couple of thousand years she mellowed somewhat and became represented more in the form of a domestic cat – or as a woman with the head of a domestic cat. In this new form she was a goddess of fertility and pregnancy probably because cats were seen to be good mothers to their kittens, taking great care over feeding and protecting them. It is also likely that because cats have lots of kittens they were seen to be particularly good animals to worship if you wanted to have lots of children. For similar reasons the mother goddess Mut was also sometimes depicted as a cat (or being with a cat).

Why were the Egyptians so crazy about cats? Well, for starters they lived in a place that had lots of small, venomous animals and cats were very good at hunting down and killing these. Of course, the cats would have been doing this out of a sense of self-preservation, but it is easy to imagine that the Egyptians could have also seen this as the cats protecting humans. Much more importantly though, cats kill rats and mice. Grains such as wheat and barley were a major part of Egyptian agriculture and if you grow grain, then you need somewhere to store it once it has been harvested. Every village would have had a grain silo of some kind, as did temples and palaces. Some stores that have been excavated in recent years are vast and would have held tonnes of grain.

Although the regular annual flooding of the Nile river was well understood and forecast by the Egyptians, there would occasionally be poor years when crop yields were much lower, so maintaining large stores of grain was essential to prevent famine. There is even a story in the Old Testament whereby Joseph made a tidy profit by building up such supplies and selling them during a famine:

...he gathered up all the food of the seven years when there was plenty in the land of Egypt, and stored up food in the cities ... And Joseph stored up grain in great abundance, like the sand of the sea, until he ceased to measure it, for it could not be measured. “So when the famine had spread over all the land, Joseph opened all the storehouses and sold to the Egyptians.”

Where you have large amounts of grain sitting around for years it is pretty likely that you are going to get large numbers of rats and mice. After all, the closest human equivalent to being a mouse in one of those grain silos is being at an all-you-can-eat buffet that lasts for eternity. As with the earlier domestication the first Egyptian cats probably started hanging around because it was an easy way to get a meal. It wasn’t long before their value was noticed and the locals began to actively breed and house them. This relationship between humans and cats soon became more than simply utilitarian, and developed into one of affection. Crown Prince Thutmose (alive approximately 3,350 years ago) was the eldest son, and original heir apparent, of Pharaoh Amenhotep III and Queen Tiye during the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt. We don’t know very much about this life, but we can be pretty sure that he loved cats. Alongside his sarcophagus was one containing his cat, Ta-miu1 – this is probably the oldest cat name that we are aware of. Even older cat-tombs have been found, some with small pots that are believed to have originally contained milk for the cats to lap at in the afterlife.

Egyptian cats were subject to great protection by law – killing or injuring one was a serious crime, indeed the Greek historian Diodorus Siculus tells the story of a Roman citizen who was lynched by an Egyptian mob around 60 BC for (accidentally) killing a cat:

And whoever intentionally kills one of these animals is put to death, unless it be a cat or an ibis that he kills; but if he kills one of these, whether intentionally or unintentionally, he is certainly put to death, for the common people gather in crowds and deal with the perpetrator most cruelly, sometimes doing this without waiting for a trial. And because of their fear of such a punishment any who have caught sight of one of these animals lying dead withdraw to a great distance and shout with lamentations and protestations that they found the animal already dead. So deeply implanted also in the hearts of the common people is their superstitious regard for these animals and so unalterable are the emotions cherished by every man regarding the honour due to them that once, at the time when Ptolemy their king had not as yet been given by the Romans the appellation of “friend” and the people were exercising all zeal in courting the favour of the embassy from Italy which was then visiting Egypt and, in their fear, were intent upon giving no cause for complaint or war, when one of the Romans killed a cat and the multitude rushed in a crowd to his house, neither the officials sent by the king to beg the man off nor the fear of Rome which all the people felt were enough to save the man from punishment, even though his act had been an accident. And this incident we relate, not from hearsay, but we saw it with our own eyes on the occasion of the visit we made to Egypt.

Despite these laws it seems as though there must have been some loopholes when it came to the killing of cats. Mummified cats were often given by pilgrims as offerings to their gods. And when I say often, I really mean often. In just the single cemetery of Beni Hasan in central Egypt more than 200,000 mummified cats were found. Most of these were then shipped to Liverpool ground up, and used as fertiliser.2 There is no way that these were all cats who died peacefully in old age of natural causes. They would have been bred, and then killed, to supply the pilgrim industry. Given their beliefs about human mummification it is quite possible that the people involved thought that this was okay, as the cats would be heading to some glorious cat afterlife.

That isn’t to say that cats were not much-loved in ancient Egypt. The Greek historian Herodotus wrote that when a cat died all of the (human) inhabitants of the house would shave off their eyebrows to show that they were in mourning. Once their eyebrows had grown back this period of grief was considered to be formally over. This may seem a little extreme, but wait till you hear what he reports they do when the household dog dies:

And in whatever houses a cat has died by a natural death, all those who dwell in this house shave their eyebrows only, but those in whose houses a dog has died shave their whole body and also their head.3

Perhaps the most extraordinary Egyptian cat story relates to the Battle of Pelusium in 525 BC when King Cambyses the Second of Persia invaded Egypt seeking that country’s throne.4 As the two armies faced each other, with battle about to commence, Cambyses ordered his troops to… bring forward armfuls of live cats (while they were Persian cats they probably weren’t Persian cats as we would know them today). and put them on the ground in front of them. The Egyptians, so fearful of injuring the cats, refused to fire their arrows at the enemy and were brutally defeated. Full disclosure, it wasn’t just cats that the Persians used, but I like to think that they were the most important animals:

When Cambyses attacked Pelusium, which guarded the entrance into Egypt, the Egyptians defended it with great resolution. They advanced formidable engines against the besiegers, and hurled missiles, stones, and fire at them from their catapults. To counter this destructive barrage, Cambyses ranged before his front line dogs, sheep, cats, ibises, and whatever other animals the Egyptians hold sacred. The Egyptians immediately stopped their operations, out of fear of hurting the animals, which they hold in great veneration. Cambyses captured Pelusium, and thereby opened up for himself the route into Egypt.

– Polyaenus, Stratagems, Book 75

The Roman and Greek empires coexisted with that of Egypt for many centuries, so you might have expected them to have adopted similar attitudes towards cats. Not the whole “worshipping them as gods and executing people who kill them” part of it, but certainly the “having them around to kill rats and mice” thing. In reality house cats were very rare in ancient Greece and Rome. It has been suggested that there was an Egyptian law that forbade the export of cats and that soldiers were even sent out to retrieve kitties that had been smuggled to other countries. Despite this being asserted as a fact in a number of places online I have been unable to track down a reliable source for it. It may be true, for sure, but I kind of doubt it.

A good reason for suspecting that there was no prohibition on the export of cats is that we know for a fact that there were domestic cats in ancient Greece at least as early as the mid-fifth century BC. Two coins from that era have been found showing the Iokastos and Phalanthos, the founders of Rhegion and Taras, playing happily with their pet cats.

These two seemed to be unusual in their feline affections. Rats and mice were a problem for the Greeks and the Romans, much as they were for the Egyptians, but they sought to address it by keeping pet weasels6 and ferrets. In the remains of the city of Pompeii, which was destroyed in AD79, hardly any cat bones have been found. Those that do appear to be from strays, they weren’t yet being kept as pets. As the centuries passed however it became clearer to the Romans that cats were simply better and, I would argue, nicer, to have around to solve rodent problems and they replaced weasels in the household.

Rats weren’t just a problem in Roman homes, they were also a problem for the Roman army – eating food stores and chewing through equipment. And it seems likely that legions travelled with cats, or at least allowed cats to settle with them. At Hadrian’s wall, the very northern limit of the Roman Empire, cat bones have been found at sites of forts such as Vindolanda. In my next piece I’ll explore the history of cats in Asia and beyond, including possibly the most perfect description of a cat ever recorded, written over 1,100 years ago, but for now I’ll leave you with a picture of the cat who currently shares my home.

Miu also mii and mau were ancient Egyptian words for “cat” and it is no coincidence that they are onomatopoeic, sounding like a cat’s mew - the word meaning “he or she who mews” which frankly I think is adorable.

Ground up mummified cats were a vital source of nitrates for UK agriculture before in invention of the Haber process to produce ammonia.

I have to confess that I was a little bit, well, disappointed when I read this. After all, I had thought that Egyptians loved cats the best but if one uses the measure of “amount of hair shaved off upon death” it is pretty clear that the dogs are ahead. A shaven head at that.

Spoiler: He totally got it.

It is worth noting that the source for this story is the Macedonian retired general and author Polyaenus who was writing almost seven hundred years after the battle took place. The great historian Herodotus, who wrote about the battle less than a century after it took place, makes no mention of the use of cats.

How do you tell the difference between a weasel and a stoat? The stoat actually is a weasel - the short-tailed weasel. No joke here!

I haven't read much about cats, but did enjoy Darnton's The Great Cat Massacre, which jumps a little into cats as a social phenomenon and how people revered, feared, etc.

this is bound to be an interesting series

As a cat lover, I love this piece of work so much! Miu😽