Who's the fool? 1628

'You shall know from your fool more secret business than from all your wise men'

We’ve just passed Blue Monday, the entirely spurious ‘most depressing day of the year’, a calculation arrived at as a PR stunt by a travel company nearly 20 years ago. But my thoughts have turned to comedy – and more particularly a 17th-century court jester who I’ve been reading about.

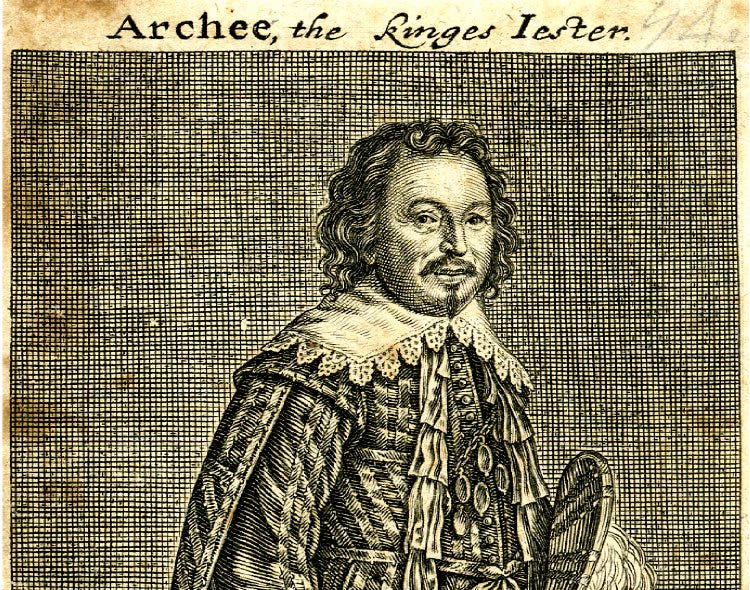

Archibald Armstrong was an intriguing figure, whose life and deeds bear witness to the Shakespearean idea of the court fool having the ear of the king, and even being able to say bold things to the monarch that others wouldn’t dare to. Although in Archy’s case, his sharp tongue did also lead to his downfall.

Little is certain about Armstrong’s early life, though he was probably born to Scottish parents (and the Armstrong surname is associated with the fabled border reivers, the lawless raiders who even then still instilled fear in the farmsteads regardless of whether English or Scots). According to some accounts, he might have been born in 1582 in the Scottish Borders; others say he was from Cumberland.

Legend has it he was caught for stealing sheep by courtiers of James I (VI of Scotland), when passing through the border country. Sentenced to death, he begged reprieve until he could finish reading his Bible. Shown mercy, he replied, ‘Then the devil take me if I ever read a word of it as long as my eyes are open’. This supposedly tickled the king, and Archy was promptly appointed court jester. Like much associated with Archy, this seems apocryphal at best, but he certainly joined the court and made himself a divisive figure, and there are many official records mentioning ‘Archy the fool’.

By 1606 he was listed among the royal servants, and in 1611 granted a life pension. Three years later a woman in London was whipped for “committing incontinency with one Archy Armstrong in the Judge’s seat”, but Archy himself presumably got away with it. Archy continued to be known for his “nimble tongue”, enjoyed a lavish lifestyle, and had favours bestowed on him – all three of which inevitably made him enemies too.

In 1623, he was even sent to Spain with Prince Charles and the Duke of Buckingham on a mission to woo the Infanta Maria Anna, whose brother, King Philip IV, was matchmaking between her and Charles. A state paper from the time records a dry note from James’s Secretary of State, George Calvert: “Archy the fool wishes to have a servant allowed, but the Privy Chamber gentlemen will complain still more if the fool is allowed the same attendance as they.”

The Spanish court found Archy entertaining, awarding him a handsome annual pension, and he was even able to get away with mocking them for the failure of the Spanish Armada 35 years earlier. For his part, he seems to have enjoyed his time there, and was sufficiently fond of King Philip that he named his own son after him in 1628. And history has recorded a letter he wrote to King James in 1623, which suggests he might also have been in a good position to be a spy – you can read it below.

Before that, though, we’d better look briefly at the jester’s trade. In 1630, a book was published in London entitled A Banquet of Jests, or Change of Cheer, being a collection of modern jests, witty jeers, pleasant taunts, merry tales.1 This edition contained nearly 200 witty vignettes, and it was so popular that over the next 30 years it ran to around 10 editions, each expanding on the last. It was originally signed ‘Anonimos’ but by the fifth edition it was being attributed to Archy Armstrong. Did he really write it? Who knows – he probably couldn’t read and write, as his letter to James was dictated to the Duke of Buckingham and signed with an ‘X’, but perhaps the book was dictated too. Here’s a flavour – 400 years later, of course, some jokes work better than others:

One making a long and tedious speech to a grave counsellor, in the conclusion thereof made an apology to excuse himself for being so troublesome—who gave him this answer: “I assure you, sir, you have not been troublesome to me at all, for all the time that you were speaking, my mind was of another matter.”

A gentlewoman suspected to be a Roman Catholic, being brought before a busy justice in the country, he would not accept of her oath, unless she would publicly call the Pope knave, to whom she answered: “Sir, if it please your Worship, it were great folly and indiscretion in me, to call any man knave whom I never either saw, or knew; but I protest, sir, if I had seen him so often, or known him so well as I do your good worship, I think I might, and with a clear conscience, too, call him knave, and knave again, and with this answer I pray you rest satisfied.”

A scholar had married a young wife, and was still at his book, preferring his serious study before dalliance with her. At length, as she was one day wantoning whilst he was reading: “Sir,” saith she, “I could wish myself that I had been a book, for then you would be still poring upon me, and I should never, night nor day, be out of your fingers.” “So would I, sweetheart,” answered he, “so I might choose what book”. To whom she again answered, “And what book would you wish me to be?” “Marry, sweet wife,” saith he, “an almanac, for so I might have every year a new one.”

It was his difficult relationship with the Church that would prove Archy’s undoing. One time, when the king was having trouble fattening up his horses, Archy supposedly suggested that his majesty make the horses bishops and they would fatten in no time. In 1625, James had died, but his successor Charles kept Archy on as his jester, even granting him 1000 acres of land in Ireland. In 1633, William Laud was appointed Archbishop of Canterbury, and Archy began to wind him up, on one occasion quipping “Great praise be given to God and little laud to the devil” (‘laud’ here meaning praise – and the archbishop was famously small of stature at only five feet tall). And in 1637, on hearing of news of Scottish resistance to James’s church policies, Archy allegedly said directly to Laud, “Who’s the fool now?”. This immediately led to him being expelled from the court, and Laud’s intervention in a later dispute Archy was involved in meant that the erstwhile jester was denied money he was owed by the Dean of York.

Four years later, Laud himself was imprisoned in the Tower of London by Parliament for treason, and in 1645 was executed. As soon as Laud was in irons, Armstrong wasted no time in publishing a pamphlet entitled Archy’s Dream; sometimes Jester to his Majesty, but exiled the Court by Canterbury’s malice, so once again the jester had the last laugh.

Although he had lost the ear of the king, Archy thrived well enough as a money lender in London before retiring to an estate in Arthuret, Cumberland, where his second son Francis had been born (to his second wife, Sybilla Bell) in 1643, and Archy lived there for another three decades on the fat of the land, dying appropriately enough on April Fool’s Day, 1672.

Below is Archy’s letter to James I, sent from Spain on 28 April 1623 – it is an intriguing mixture of arrogant, fond and perceptive, which seems appropriate for this complex character.2

Most great and gracious King.

To let your Majesty know, never was fool better accepted on by the King of Spain, except his own fool; and to tell your Majesty secretly, I am better accepted on than he is. To let your Majesty know, I am sent for by this King when none of your own nor your son’s men can come near him, to the glory of God and praise of you. I shall think myself better and more fool than all the fools here, for aught I see; yet I thank God and Christ my Saviour, and you, for it. Whoever could think that your Majesty kept a gull and an ass in me, he is a gull and an ass himself.

To let your Majesty know, that I cannot tell you the thoughts of kings’ hearts; but this King is of the bravest colour I ever saw, yourself except. And this King will not let me have a trunchman [interpreter]. I desire your Majesty’s help in all need, for I cannot understand him; but I think myself as wise as he or any in his Court, as grave as you think the Spaniard is. You will write to your son and Buckingham, and charge them to provide me a trunchman, and then you shall know from your fool, by God’s help and Christ’s help, and the Virgin Mary’s, more secret business than from all your wise men here.

My Lord Aston,—your Majesty shall give him thanks,—writes to you and to your son; do give him thanks, for never kinder friend I found in this world; his house is at my command, and besides he gave me white boots when my own trunk was not come up.

I think every day of your self, and of your Majesty’s gracious favour; for you will never be missed till you are gone, and the child that is unborn will say a praise for you. But I hope in God, for my own part, never to see it. The further I go, the more I see, for all that I see here are foolery to you. For toys and such noise as I see, with God’s grace, my Saviour’s, and your leave, I will let you know more whenever I come to you; and no more, with grief in my eyes and tears in my heart, and praying for your Majesty’s happy and gracious continuous among us.

Your Majesty’s Servant, Archibald Armstrong,

your X best fool of state, both here and there.