Watch your step! 1786

And don't be Johnny Raw!

Here in the Cotswolds, where I’m lucky to live, a friend of mine likes to tell the story of when he first moved here and overheard a group of local lads in the pub. “The thing about that London,” one of them opined, “is to never look anyone in the eye.”

City life is different from country life – this has been a truism for centuries, and I have recently come across a rich seam of literature which provides advice, guidance and warnings to unwary noobs either visiting or moving home to the metropolis. (I’m indebted to Dr Alison O’Byrne at the University of York for this, having edited her forthcoming book The Art of Walking in London: Representing the Eighteenth-Century City, 1700–1830, to be published by Cambridge University Press in November.)

Some of these works are very entertaining. Here, for example, is one bit of advice from the 1818 book The London Guide and Stranger’s Safeguard against the Cheats, Swindlers, and Pickpockets… by ‘A Gentleman who has made the Police of the Metropolis an Object of Enquiry Twenty-Two Years’ in a section about ‘Walking the Streets’. In order to avoid criminals, you must pretend to be one yourself, he says. If you

… appear like a thorough bred cockney in your gait and manner, by placing the hat a little awry, and with an unconcerned stare, penetrating the wily countenances of the rogues, you attain one more chance, at least, of escaping the snares that are always laid to entrap the countryman or new comer: these latter are easily recognized by their provincial gait, dialect, and cut of the cloth; by the interest they take in the commonest occurrences imaginable, and the broad stare of wonder at every thing they see. Such men attract the attention of passers-by of every degree; and, it would be surprising indeed, if the knavish part of the community did not endeavour to profit by the want of knowledge apparent in Johnny Newcome, or Johnny Raw, as such men are aptly called. He is followed for miles, sometimes for an entire day or more, by a string of pickpockets or highwaymen, until they can find an opportunity to do him.1

Nobody wants to be Johnny Raw, right?

(The ‘gentleman’ who wrote the book isn’t named, but is believed to have been John Badcock, who mostly wrote books about boxing and horse racing in the early 19th century.)

But the main text I give you this week is a handy list of tips entitled ‘On walking London streets’. It was published in 1786 in The London Adviser and Guide: containing every instruction and information useful and necesssary to persons living in London and coming to reside there by the Rev Dr John Trusler.

Born in London, Trusler (1735–1820) is an entertaining character. His father ran a tavern and tearoom in Marylebone and his mother came from a family of Wiltshire clothiers. They wanted John to receive a good education, so they sent him to Westminster School; he went on to Cambridge, worked as a curate in various southern English counties, and then returned to London, first as a minister at St Clement Danes in the Strand. He married three times.

Trusler also diversified somewhat in his career: he set up an academy for teaching oratory; he practised – or at least styled himself – as a medical doctor; and set up a Literary Society intended to stand alongside the Royal Society for the sciences. This society in turn set up a publishing house, the Literary Press – which mostly published works by John himself. The Dictionary of National Biography notes that he produced works on “topics as diverse as medicine, farming, history, politeness, law, theology, travel, and gardening”, as well as self-help books, almanacs… and apparently the first ever thesaurus in English. He also had a scheme to publish sermons in a handwriting script for lazy priests to buy and pretend they’d written themselves. I can imagine him running a modern ‘essay farm’ for students.

But back to The London Adviser – this is packed with information on how to rent a house, where to shop, where to post letters, details of transport (and how to deal with coach and cab drivers), local newspapers… and much more besides, along with how much everything cost. It’s rather impressive!2

And here are those useful (if perhaps a little obvious) tips on negotiating the streets – I hope you still find them helpful if you visit London in 2024!

On walking London streets

In walking through London, you may always find your way, if, before you set out, you will consult a map of London, and attend to the names of the streets and courts, which are always painted on a board against the houses, at the corner of each street or court. [Signs with street names were a recent innovation of the 1760s.]

If you wish to walk safe, never pass under any goods, &c. that are drawing up to the top of a house by a crane, nor pass a house where the bricklayers are at work, lest any thing should fall on your head; it is adviseable, on such occasions, to cross the way: and if you would save your clothes, never pass under a lamp, whilst the lamp-lighter is triming it, nor go near any rails, &c. fresh painted; or contest the way with a baker, barber, chimney-sweeper, barrow-woman, &c.

If the wall or houses are on your right hand, keep the wall and you will have no interruption, every one will give way.

But don’t dispute the wall with a cart or carriage, lest you should be crushed.

Never stop in a crowd, or to look at the windows of a print-shop or shew-glass, if you would not have your pocket picked.

Do not walk under a pent-house, lest persons watering flower-pots, or other slops, should drop upon your head.

Be careful, if you meet a porter carrying a load upon his head, that you do not get a blow that may be fatal.

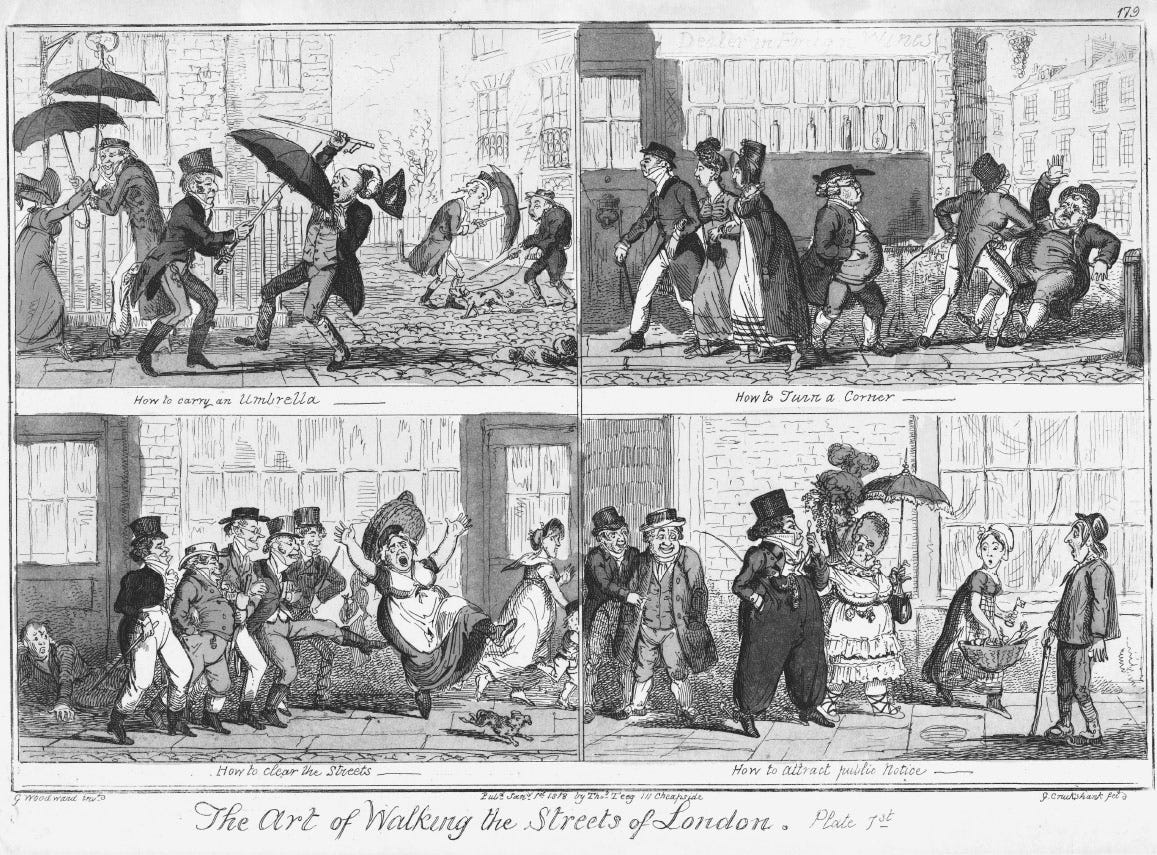

If you walk with an umbrella, and meet a similar machine, lower yours in time, lest you either break it, or get entangled with the other.

One side of the way is generally shady; it is not necessary perhaps to recommend crossing to the shady side in sultry weather, or keeping to windward when the dust flies.

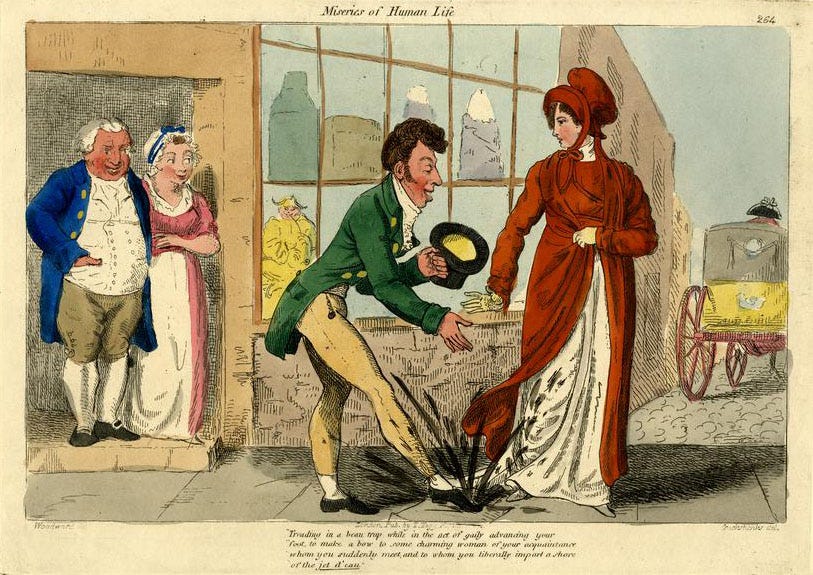

In wet weather look where you step; if you would not be splashed, don’t tread on a loose stone. [See below.]

Don’t hastily cross a street when a coach is coming up, lest your foot should slip and you be run over.

In frosty weather it is adviseable to walk in the coach-ways, which are not so slippery as the foot-paths; and to bind a piece of cloth-list round one of your shoes, it will save you many a fall.

It is very dangerous walking in a thick fog, as you cannot see the danger before you; people who walk in London should always look before them, both above and below.

It would be prudent for the men to have their coat-pockets open in the lining within; this will often prevent them from being picked. At least every one should attend to his pocket at night, or as he passes a crowd.

One last note on No 10’s ‘loose stone’ theme… a particular point of focus of Trusler’s era was the ‘beau-trap’ – a loose paving slab that could trip the unwary nattily-attired ‘beau’ as he sauntered along. In Miseries of Human Life (1806), James Beresford warned of “treading in a beau-trap, while in the act of smartly advancing your foot to make a bow to some charming woman of your acquaintance, whom you suddenly meet, and to whom you liberally impart a share of the jet d’eau”. Isaac Cruikshank gave us a handy depiction of this scene:

Mind how you go.

What a charming list of instructions for walking in London! Having lived there for close to a decade, I think many early-morning commuters could learn a thing or two from this… 🤣