Today in history: November 7

Three explosive events of very different kinds…

This week’s little stories from contemporary historical sources…

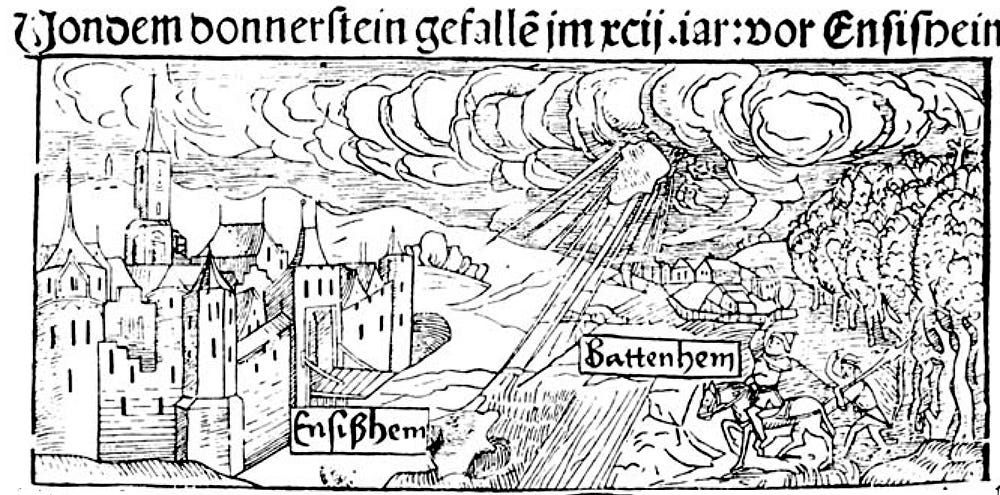

Fireball from the heavens, 1492

It’s 1492 (again). A thunderous fireball shakes the Upper Rhine, a 127 kg (280 lbs) meteorite landing in a wheat field outside the village of Ensisheim in what is now Alsace, France – the explosion is heard up to 150 km (93 miles) away . The “heaven-sent stone” draws the attention of the humanist and satirist Sebastian Brant (best known for The Ship of Fools),1 who rushes a poetic broadsheet into print at Basel – Latin verses with facing German, casting the fireball’s fall as a divine omen favouring the Habsburg army. The Ensisheim stone, as it became known, was chained up in the church; and Brant’s verses and subsequent chronicles influenced by them turned it into a pan-European marvel. Here’s an extract of Brant’s verses (translated from the Latin):

… toward its middle course that day was tending

When thunder rumbled and lightning crackled terribly through the air,

with many a sound: here a huge stone crashed,

whose shape is of a delta, and the edge triangular: it was scorched

in colour and in the form of earthly metal.

Thrown from a slant it is said; and it was seen under the waves

of Saturn which kind of star has to send.

Ensisheim had perceived it, St. Gallen felt it; into the fields

it then leapt, ravaged the ground there,

which though dispersed into parts everywhere,

still retains weight: behold you see.

Indeed what wonder that it could fall in days of winter

or that a heap should form in such cold?

…

Whatever it is, it portends something great, believe that it will be:

but may it come upon enemies, I pray, upon the wicked.

This in fact the world’s first datable account of a specific meteorite strike. A good chunk of the stone survives to this day, too – a 56 kg (123 lb) lump of chondrite (unmelted stony meteorite). For a 500th-anniversary history, Ursula B. Marvin wrote that “the stone’s survival depended on the presence of a magistrate at Ensisheim who forbade the removal of pieces, which had begun apace as soon as a crowd gathered and pulled the stone out of a 1m hole in a wheat field. He ordered the stone brought into the city to await the arrival of King Maximilian…”2 Brant’s verses were in fact an attempt to urge Max to make war on the French – which he did (and won).

The stone itself remained in Ensisheim church until 1793, when French Revolutionaries moved it to a museum to be studied; what was left went back to the church, and the surviving lump is now still in Ensisheim, at the Hotel de Ville.

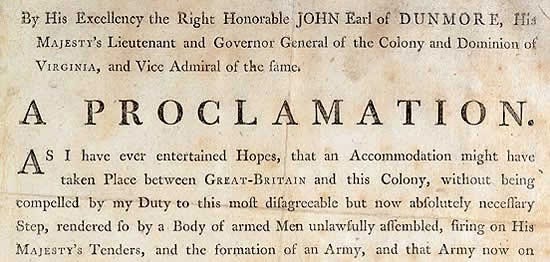

A political fireball, 1775

In the anxious first months of the American War of Independence, Virginia’s royal governor, John Murray (Earl of Dunmore), tried to break Patriot support by offering freedom to enslaved people owned by “rebels” who would join the British. The text was first posted from his flagship off Norfolk, Virginia on 7 November 1775 – exactly 250 years ago today – then reprinted widely in colonial newspapers – causing a political explosion that echoed from plantations to Parliament. Here’s part of the text of the ‘Dunmore Proclamation’:

As I have ever entertained Hopes that an Accommodation might have taken Place between Great-Britain and this colony, without being compelled by my Duty to this most disagreeable but now absolutely necessary Step, rendered so by a Body of armed Men unlawfully assembled, bring on His MAJESTY’S Tenders, and the formation of an Army, and that Army now on their March to attack His MAJESTY’S troops and destroy the well disposed Subjects of this Colony. To defeat such unreasonable Purposes, and that all such Traitors, and their Abetters, may be brought to Justice, and that the Peace, and good Order of this Colony may be again restored, which the ordinary Course of the Civil Law is unable to effect; I have thought fit to issue this my Proclamation, hereby declaring, that until the aforesaid good Purposes can be obtained, I do in Virtue of the Power and Authority to ME given, by His MAJESTY, determine to execute Martial Law, and cause the same to be executed throughout this Colony: and to the end that Peace and good Order may the sooner be restored, I do require every Person capable of bearing Arms, to resort to His MAJESTY’S STANDARD, or be looked upon as Traitors to His MAJESTY’S Crown and Government, and thereby become liable to the Penalty the Law inflicts upon such Offences; such as forfeiture of Life, confiscation of Lands, &c. &c. And I do hereby further declare all indentured Servants, Negroes, or others, (appertaining to Rebels,) free that are able and willing to bear Arms, they joining His MAJESTY’S Troops as soon as may be, for the more speedily reducing this Colony to a proper Sense of their Duty, to His MAJESTY’S Crown and Dignity…

A strange form of ‘freedom’, perhaps – hardly one without strings. The colonial leaders were furious, and promised that “all negro or other slaves, conspiring to rebel or make insurrection, shall suffer death”, organising patrols to look out for them. A thousand or so did make it through to become part of ‘Dunmore’s Ethiopian Regiment’, and further slave emancipations took place a few years later – though Dunmore left in 1776 and only took 300 of them with him.

Another political fireball, 1917

What we call the ‘Russian Revolution’ was in fact two events, both in 1917 – first the February Revolution, with mass protests against food shortages and the autocratic rule of Tsar Nicholas II, leading to his abdication; and the the October Revolution. But in fact it only took place in October according to the old Julian calendar (still in use in Russia at the time) – by the Georgian calendar,3 it took place on the night of 7–8 November.

On that night, the Petrograd Military Revolutionary Committee announced the overthrow of the Provisional Government installed in February. Within hours, proclamations and decrees ran in the newspapers and were posted across the city. Here’s what a young chap called Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov, leader of this coup – better known to history by his pseudonym Lenin – proclaimed in the magazine Robochy I Soldat:

The Provisional Government has been deposed. State power has passed into the hands of the organ of the Petrograd Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies—the Revolutionary Military Committee, which heads the Petrograd proletariat and the garrison.

The cause for which the people have fought, namely, the immediate offer of a democratic peace, the abolition of landed proprietorship, workers’ control over production, and the establishment of Soviet power—this cause has been secured.

Long live the revolution of workers, soldiers and peasants!

That communist revolution and its consequences are of course still with us today.

An allegory railing against a society run by idiots – sound familiar?

‘The meteorite of Ensisheim: 1492 to 1992’, Meteoritics, vol. 27, March 1992.

Adopted by Britain in 1752 (along with its American colonies at the time).

Russia has spread its errors as Our Lady of Fatima predicted................................The Union also encouraged the enslaved to flee the plantations and join the Union Forces. Quite a frightening proposition for slave holders who might have been in the war effort fronts. Thanks!