Today in history: August 29

A king fights at sea, a technological breakthrough, a last man standing…

This week’s little stories from contemporary historical sources…

Sound the trumpets (silence the minstrels), 1350

The scene: the English Channel, not far from the port of Winchelsea, newly rebuilt on higher ground after a huge flood had destroyed the old town in 1287. The combatants: around 50 English ships, under the command of Edward III, and a similar number of Castilian ones – the battle became known as Les Espagnols sur Mer, the Spaniards on the Sea, aka the Battle of Winchelsea, where the court ladies stood on the hill and watched events unfold.

This battle would later be seen as part of the Hundred Years’ War1 between England and France, but in this case the French had outsourced blockading English ports to the Crown of Castile (the major part of what we now call Spain).

By 1350, the English were winning on points: Edward III had victories at Sluys (1340) and Crécy (1346), but his finances (and his wine cellar) depended on keeping hold of Bordeaux in France. And when the French commissioned Charles de la Cerda, a Franco-Castilian nobleman with a thirst for blood, the tables began to turn: he captured numerous English ships laden with wine and threw their crews overboard. More was planned.

When Edward III got wind of this, he decided to confront the raiders himself: according to the main chronicler of these events, “they must be chastised”, he said. He set out in late August with an estimated 50 ships, and his sons Edward (‘the Black Prince’, born only five miles from where I’m sitting in Oxfordshire) and the young John of Gaunt went with him – and they would definitely see action.

One of the main sources for all this was in fact a Frenchman, Jean Froissart, who began working for Edward’s French wife Philippa around a decade or so after these events. Froissart travelled extensively around Britain and Europe gathering eyewitness accounts for his Chronicles of the era. Froissart was a close contemporary of Chaucer, and they almost certainly knew each other at court. He is also about as close as we can get to the real events of the battle (while bearing in mind that he was effectively working for the English), and he had a cinematic eye.

Froissart sets the scene, bigging up the Spanish forces:

…they had marvellously provided themselves with all sorts of warlike ammunition; such as bolts for cross-bows, cannon, and bars of forged iron to throw on the enemy, in hopes, with the assistance of great stones, to sink him… it was a fine sight to see them under sail. Near the top of their masts were small castles, full of flints and stones, and a soldier to guard them; and there also was the flag-staff, from whence fluttered their streamers in the wind… The Spaniards were full ten thousand men…

Those “small castles” were a key new feature of the Spanish warships: raised fighting platforms at both ends which towered above the much smaller English vessels. Our colourful chronicler now turns to the English, who were amusingly casual:

The king posted himself in the fore part of his own ship: he was dressed in a black velvet jacket, and wore on his head a small hat of beaver, which became him much. He was that day, as I was told by those who were present, as joyous as he ever was in his life, and ordered his minstrels to play… Whilst the king was thus amusing himself with his knights, … the watch, who had observed a fleet, cried out, “Ho, I spy a ship…” The minstrels were silenced… The trumpets were ordered to sound, and the ships to form a line of battle for the combat… The Spaniards now drew near,… bore instantly down on them, and commenced the battle.

There follows a dramatic account of Edward III’s ship being damaged in a collision – it “let in water, which the knights cleared, and stopped the leak, without telling the king any thing of the matter”:

…another large ship bore down, and grappled with chains and hooks to that of the king. The fight now began in earnest, and the archers and cross-bows on each side were eager to shoot and defend themselves. The battle was not in one place, but in ten or twelve at a time. Whenever either party found themselves equal to the enemy, or superior, they instantly grappled, when grand deeds of arms were performed. The English had not any advantage; and the Spanish ships were much larger and higher than their opponents, which gave them a great superiority in shooting and casting stones and iron bars on board their enemy, which annoyed them exceedingly. The knights on board the king’s ship were in danger of sinking, for the leak still admitted water: this made them more eager to conquer the vessel they were grappled to : many gallant deeds were done; and at last they gained the ship, and flung all they found in it overboard, having quitted their own ship.

So the English prevailed, sinking as much as half the Spanish fleet, and six years later the Black Prince would have another decisive victory at Poitiers in central France. But four years after that, the French came back and burned down much of Winchelsea – and in the bigger war, the tide would turn in their favour.

Transformer man, 1831

And now for a different kind of electrifying scene. English scientist Michael Faraday (1791–1867) is in his lab again, trying something new. He has already spent a decade trying to make electric motors and studying magnetism – and hoping to bring these together. He writes in his notebook on August 29th:

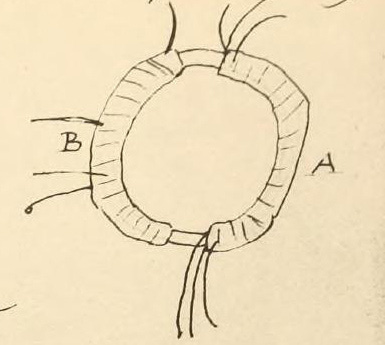

Have had an iron ring made (soft iron), iron round and 7/8 inches thick and ring 6 inches in external diameter. Wound many coils of copper wire round one half, the coils being separated by twine and calico… Will call this side of the ring A. On the other side but separated by an interval was wound wire in two pieces together amounting to about 60 feet in length, the direction being as with the former coils; this side call B.

Charged a battery… Made the coil on B side one coil and connected its extremities by a copper wire passing to a distance and just over a magnetic needle (3 feet from iron ring). Then connected the ends of one of the pieces on A side with battery; immediately a sensible effect on needle…

Made all the wires on A side one coil and sent current from battery through the whole. Effect on needle much stronger than before.

That iron ring with wires wound round it would transform the world. What Faraday had proven with this apparatus2 was that a current in one coil could induce a magnetic field and current in the other – and had effectively created the world’s first transformer, technology which underpins all of today’s power grids and countless electronic devices. He would continue that year to explore electromagnetic induction, and the ‘Faraday disc’ he then developed was the forerunner of the dynamo.

Last of his people, 1911

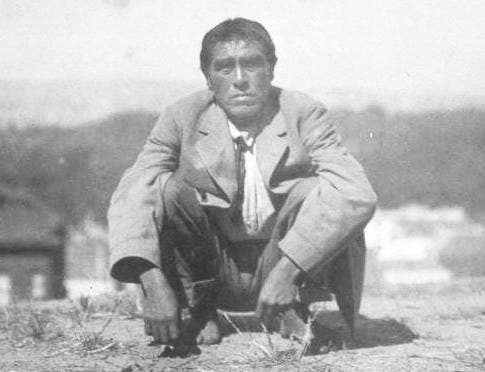

It’s August 29th 1911 and a starving, desperate man around 50 years of age staggers into the yard of Ward’s Slaughterhouse in Oroville, California. He has spent the last three years alone in the wilderness, now driven out by forest fires. A group of engineering surveyors had come across the family’s remote camp back in 1908, prompting his last surviving relatives to scatter in panic. The surveyors took his possessions as souvenirs; his family would not survive.

This was the Native American who became known as Ishi – not his real name, but simply ‘man’ in his Yahi language. He is believed to be the last such Indigenous person in the US to make contact with the settlers. And in many cases, contact in the past had not been good: in the wake of the Californian Gold Rush, the Yahi in particular had been massacred by settlers, the population dwindling until only Ishi’s family – and then him alone – were left.

His arrival became a sensation. By October, he had also caught the attention of Berkeley anthropologists Alfred L. Kroeber and T.T. Waterman, who interviewed him at length – a slow process of mime and faltering conversation through Yana, a related Native American language.

In an early letter to Kroeber, Waterman noted:

This man is undoubtedly wild. He has pieces of deer thong in place of ornaments in the lobes of his ears and a wooden plug in the septum of his nose. He recognizes most of my Yana words and a fair proportion of his own seem to be identical [with mine]. Some of his, however, are either quite different or else my pronunciation of them is very bad, because he doesn’t respond to them except by pointing to his ears and asking to have them repeated… We had a lot of conversation this morning about deer hunting and making acorn soup, but I got as far as my list of words would take me.

Although many accounts of Ishi have been written,3 providing great detail on a lost way of hunter-gatherer life, it is hard to get to his own words directly, not least because he only began to pick up English gradually. Waterman promptly took Ishi to San Francisco for closer study, and Ishi worked as a university janitor. How Ishi was treated is a complex ethical subject – for example, he became part of a living museum exhibit for a while, demonstrating arrow making, and newspapers revelled in describing him as a ‘savage’. But when he was given the opportunity to return to Deer Creek, he is reported to have said (in Yahi):

I will live like the call-tu [white man] for the remainder of my days. I wish to stay here where I now am. I will grow old in this house, and it is here where I will die.

And asked if he wanted some shoes, he replied: “I see the ground is stone here. Walking on that all the time, I would wear out shoes; but my feet shall never wear out.”

Sadly his death came all too soon: first hit by respiratory infections only weeks after arriving in San Francisco, his health continued to falter in this unfamiliar environment, and he died of tuberculosis in March 1916. So it goes.

Yes, all 116 years of it: c.1337–1453.

The iron ring is preserved to this day in London’s Faraday Museum.

The most renowned is by Kroeber’s wife Theodora, Ishi in Two Worlds (1961) – she never met Ishi but had her late husband’s notes.