The week in history: January 2–8

An arrogant king, an innocent man, a missing woman

This week’s little stories from contemporary historical sources…

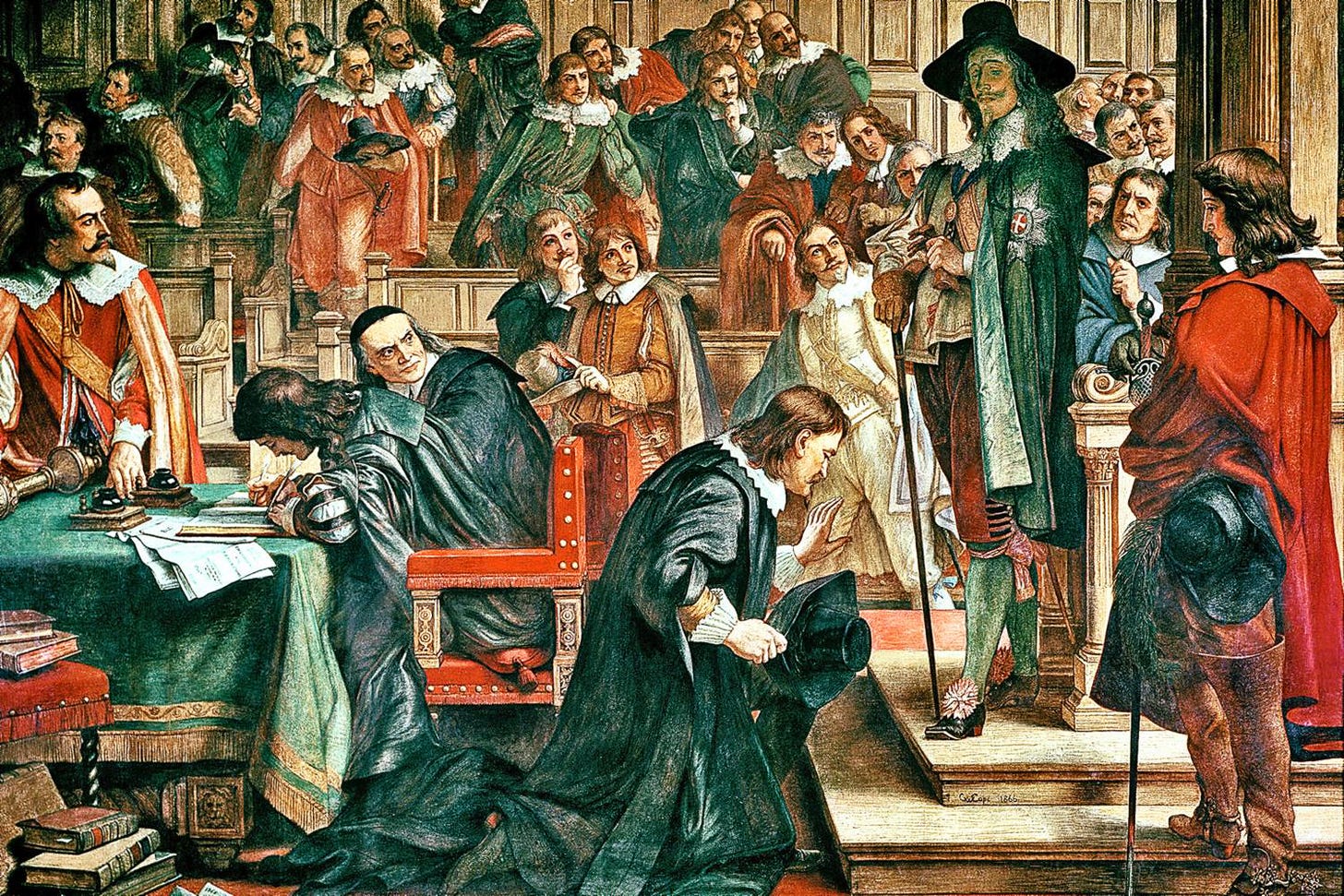

A king loses control, 1642

By early 1642, the struggle between King Charles I and Parliament had reached a dangerous pitch. Parliament had been pushing back against royal policy and finances, and Charles – feeling authority slipping – decided on an act of theatre backed by force: he would personally enter the House of Commons with armed men and seize leading opponents for treason. It was a move that crossed a line. The Commons was not just another room in the palace; it was the symbolic heart of parliamentary privilege.

On January 4, 1642, Charles walked into the chamber (backed up by 400 soldiers) and demanded five MPs (Denzil Holles, John Pym, Sir Arthur Haslerig, John Hampden and William Strode). But they had been warned and were gone. What followed – especially the Speaker’s carefully worded refusal to assist the King – became one of the defining moments in the story of constitutional monarchy.

The clerk of the Commons was recording proceedings until the King ordered him to stop. What he noted survives in the House of Commons Journal:

King Charles sits in the Speaker’s Chair and Speaks to the Commons:

His Majesty came unto the house and took Mr. Speakers Chair.

Gentlemen I am sorry to have this occasion to come unto you.

A 1650 compilation of writings by or about Charles, the Reliquiae Sacrae Carolinae, takes up the story with the rest of the king’s speech:

I am sorry for this occasion of coming unto you: yesterday I sent a Serjeant at Armes upon a very important occasion, to apprehend some that by my command were accused of High Treason, whereunto I did expect Obedience, and not a Message. And I must declare unto you here, that albeit no King that ever was in England shall be more careful of your Priviledges, to maintain them to the uttermost of his power then I shall be; yet you must know, that in cases of Treason, no person hath a priviledge, and therefore I am come to know if any of those persons that were accused are here; for I must tell you, Gentlemen, that so long as these persons that I have accused (for no slight crime, but for Treason) are here, I cannot expect that this House can be in the right way that I do heartily wish it: Therefore I am come to tell you, that I must have them wheresoever I finde them.

But the five men had already fled. When Charles demanded of the Speaker of the House, William Lenthall, whether the men were present (“Mr Speaker, I must for a time make bold with your chair”), Lenthall famously replied:

May it please Your Majesty, I have neither eyes to see, nor tongue to speak in this place, but as the House is pleased to direct me, whose servant I am here, and I humbly beg Your Majesty’s pardon that I cannot give any other answer than this to what Your Majesty is pleased to demand of me.

This is held to be the first time that a Speaker had asserted his duty to Parliament over the monarch. And this is Charles’s alleged reply:1

Well, [since] I see all the Birds are flown, I do expect you, that you shall send them unto me, as soon as they return hither.

And according to one eyewitness, Sir Simonds D’Ewes, who had been keeping a journal of parliamentary proceedings, Charles stormed off “in a more discontented and angry passion than he came in”.

The attempted arrests quickly destroyed trust. London turned openly hostile to the King; Charles left the capital a few days later (only returning for his execution), and the slide into full civil war accelerated. Politically, the episode hardened the idea that the monarch could not simply override parliamentary privilege by force – and it permanently elevated the Speaker’s role as servant of the House rather than agent of the Crown.

Also this week…

A soldier loses face, 1895

France in the 1890s was politically brittle: nationalism, fear of espionage and antisemitism were powerful currents, and the army’s prestige was treated as a national pillar. When Captain Alfred Dreyfus, a Jewish officer, was accused of passing secrets to Germany, the case quickly became more than a trial – it became a test of whose ‘truth’ would prevail: institutional certainty or evidentiary rigour.

On January 5, 1895, Dreyfus was brought before troops for the ritual of military degradation – his insignia torn away, his sword broken – meant to be both punishment and public warning. The power of the event is that Dreyfus himself left an account of what it felt like to be the body at the centre of the spectacle.

This is Dreyfus describing the degradation itself:

The degradation took place Saturday, the 5th of January. I underwent the horrible torture without weakness.

Before the ceremony, I waited for an hour in the hall of the garrison adjutant at the Ecole Militaire, guarded by the captain of gendarmes, Lebrun-Renault. During these long minutes I gathered up all the forces of my being…

I protested against the vile accusation which had been brought against me; I recalled that I had written again to the Minister to tell him of my innocence…

After this I was marched to the centre of the square, under a guard of four men and a corporal.

Nine o’clock struck. General Darras, commanding the parade, gave the order to carry arms.

I suffered agonizingly, but held myself erect with all my strength. To sustain me I called up the memory of my wife and children.

As soon as the sentence had been read out, I cried aloud, addressing myself to the troops:

“Soldiers, they are degrading an innocent man. Soldiers, they are dishonoring an innocent man. Vive la France, vive l’armee!”

A Sergeant of the Republican Guard came up to me. He tore off rapidly buttons, trousers stripes, the signs of my rank from cap and sleeves, and then broke my sword across his knee. I saw all these material emblems of my honour fall at my feet. Then, my whole being racked by a fearful paroxysm, but with body erect and head high, I shouted again and again to the soldiers and to the assembled crowd the cry of my soul.

“I am innocent!”

The parade continued. I was compelled to make the whole round of the square. I heard the howls of a deluded mob, I felt the thrill which I knew must be running through those people, since they believed that before them was a convicted traitor to France; and I struggled to transmit to their hearts another thrill,—belief in my innocence.

The round of the square made, the torture would be over, I believed.

But the agony of that long day was only beginning.

They tied my hands, and a prison van took me to the Depot (Central Prison of Paris), passing over the Alma Bridge. On coming to the end of the bridge, I saw through the tiny grating of my compartment in the van the windows of the home where such happy years of my life had been spent, where I was leaving all my happiness behind me. My grief bowed me down.

At the Central Prison, in my torn and stripped uniform, I was dragged from hall to hall, searched, photographed, and measured. At last, toward noon, I was taken to the Sante Prison and shut up in a convict’s cell.

The degradation was not the end; it was the beginning of the affair’s long afterlife. Dreyfus – who was indeed innocent – was sent to Devil’s Island, a penal colony in French Guiana, and the controversy metastasized into one of modern Europe’s defining political battles: press campaigns, forged evidence claims, whistleblowing, and the eventual split between ‘Dreyfusards’ and anti-Dreyfusards. Its consequences shaped debates about antisemitism, civil rights, the authority of militaries in republics, and the responsibilities of intellectuals in public life.

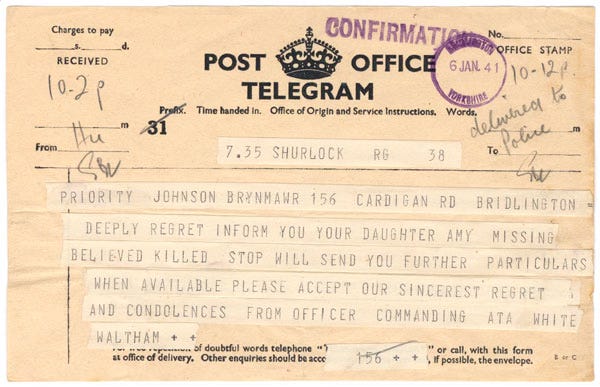

A pilot loses control, 1941

Amy Johnson was already a household name: record flights, celebrity and the image of modern aviation wrapped in one person. But in wartime, fame doesn’t exempt you from risk. With Britain fighting for survival, many civilian pilots were pulled into ferrying work – moving aircraft, doing essential but hazardous flights under bad weather, blackout conditions and relentless operational pressure.

Around January 5, 1941, Johnson’s aircraft went down near the Thames Estuary. What makes this story unusually vivid is that witnesses described a parachutist in the water calling for help – “Hurry, please hurry”. She was drifting towards HMS Haslemere nearby – but vanished under the ship – and sadly the ship’s captain Walter Fletcher also died from exposure after diving in to try and rescue her. Rumours persist to this day about why she was on the journey, whether she was shot down and precisely how she died.

As a poignant final note, here is the telegram sent to her father Will:

And here’s part of a diary entry written by Will a few days later and preserved by the RAF Museum:

It was a heavy time for us all between 11.45 & 3.30 as that is just a week since Amy did her fatal flight. At 3.30 we drank a silent toast to the Memory of Amy…

If you’d like to keep up with the latest discoveries in the world of British history, sign up here to my new sister newsletter:

Victorian accounts rather embellish this scene, prefacing Charles’s reply with “Well, well. I think my eyes are as good as another’s.”

Chas I, the first(?) Christian Monarch regicide, coming from Enlightenment (?) reasoning. Thank you and Blessings for a good new year!

It is the last of these that touches me most. An excerpt from my mother's mémoire, about my father:

While the Cornish winter was much more agreeable than that I’d been used to, that January brought sea fog rolling in like a blanket, strangely coinciding with a Night-Flying Exercise which was scheduled for the Squadron. On the Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday evenings Ron reported for duty only to be told that the Exercise was “scrubbed” due to the fog. Conditions were even worse on Thursday and again it was cancelled. As we partook of our evening meal on Friday Ron decided to ring the Duty Officer, certain that with the fog thicker than ever, reporting for duty would prove a fruitless journey. When he re-joined me he was still confident that cancellation was bound to be forthcoming when he would take me to a movie. I couldn’t believe it when he rang from Camp to tell me that the Exercise was “on” due no doubt, to the insistence of a Wing Commander who was more concerned with rigid records accountability than with the safety of a fleet of Lancaster bombers and their crew personnel. Alone I stood by our Lounge window—unable to even distinguish the wrought-iron verandah a few feet beyond—and despite the muffling effect of the impenetrable fog, I listened to the heavy drone of aero engines as wave after wave passed from Newquay out over the ocean. I fell asleep eventually—then suddenly awoke with a start to find Ron, his face ashen, leaning over me. I thought I was dreaming. His ’phone call had warned me that IF they actually did take off they’d never be able to land again, in such conditions, at St. Mawgan—and it could be days before he returned, were he to divert to the likes of Kinloss or Ballykelly. It was 5 a.m. when I realised he was back—and learned that he had returned to the sister Station of St. Eval (only a few miles away from St. Mawgan) which had the facility of radar and he had been “talked down” by St. Eval A.T.C. However, while you trust in their directions, they cannot “land” you, but leave you to your own decisions for the last, crucial 50 feet of descent. It is a miracle that no Lancs. were written off that dreadful night—Ron managed his ’plane on to the ground, but to taxi was out of the question, nor could the dispersal lorries, sent out to collect personnel, find them—more by accident than design in the end. It had been quite an experience and happily was the last night-flight Ron ever was called upon to do.