The very bowels of the earth, 1926

Psychological excavations… and some early urban explorations

Last weekend I was in Liverpool, and had the opportunity to visit the Williamson tunnels – a fantastic experience. This, of course, made me want to write about the man who created them – but the whole story, like the underground empire he created, is confusingly labyrinthine. Let me explain.

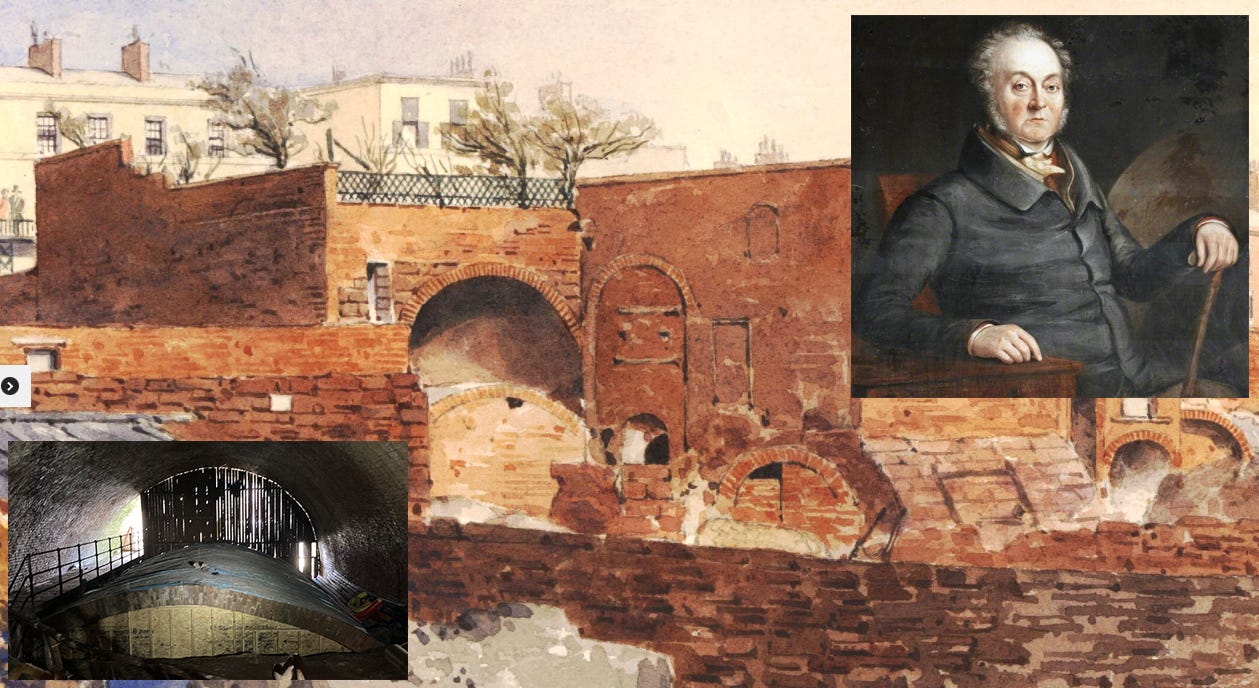

The Williamson tunnels are an extraordinary collection of excavations made over 30+ years in the early 19th century at the behest of Liverpool tobacco and snuff magnate Joseph Williamson – and nobody really knows why. Williamson was born in humble circumstances in Yorkshire in 1769, but during his childhood his family moved to Warrington and then Liverpool, both then in Lancashire. He got a job with tobacco merchant Richard Tate and worked his way up the ladder, helped by marrying the boss’s daughter Elizabeth in 1802. Eventually, Joseph took over the business and made his fortune. But it’s what he spent that on that made him (in)famous.

In 1805, Joseph bought some land on a sandstone outcrop at Edge Hill, a couple of miles east of the centre of Liverpool – a city that was then exploding with growth thanks to international trade (and, of course, underpinned by slavery) – and then started building houses. These were eccentric enough in their design, but they were soon followed by more unusual projects: employing men to quarry out the sandstone,1 he then had the cavities covered over with brick arches, and over time this work extended to excavating tunnels all over the area, accelerating after the death of his wife in 1822. Even today, nobody knows their full extent, and since his death in 1840, when this work abruptly stopped, many of them gradually filled up with rubble and access was lost. Thanks to the work of two charities, some of the tunnels are open to the public, and excavation work continues.2

Why did he do all this? There are various theories, from a grand expression of neurodivergence to generous philanthropy – providing labour for labour’s sake to employ the city’s poorer workers, from being a millenarian cult prepper3 to secret government munitions storage, or even that it was an elaborate tax evasion scheme (stone laundering, if you like).

What do we know of the man? Ah, there’s a question, as hardly any first-hand material by Williamson survives (maddeningly, his housekeeper burned his papers). There is only one known account of him during his lifetime, a whimsical profile in a local magazine, The Rambler in 1837, which very much confirms his philanthropic spirit and tells us…

This truly original independent and spirited gentleman has been known in Liverpool for the last half-century… [After the death of his wife] he retired from public life and secluded himself within the bosom of his family circle; but that… caused a vacuum in his life…

From about this period we may date the decided eccentric turn which has characterised the subject of our sketch up to the present day. But in the indulgence of this humour, no design undistinguished by some benevolent purpose was ever undertaken by this singular philanthropist.

The most extraordinary and unprecedented ideas of architecture and subterranean research, which are the leading features in Mr. Williamson's character, we shall leave to the curious speculator on the human mind to account for…

…the most extraordinary characteristic that distinguishes Mr. Williamson is his rage for excavation. Round about his residence subterraneous passages branch off in every direction… There are rooms of good size hollowed from the solid rock, and passages leading therefrom as numerous as the rays of the sun!

And that’s about as close as we can get, although an obituary published in the Liverpool Mercury on 8 May 1840 confirms the picture:

This gentleman died on Friday, at his residence, Edge-hill, after an illness of only two days, in the seventy-first year of his age. The disease which terminated his existence was, we understand, water on the chest. Mr. Williamson was a person of very eccentric habits, and well known in his own neighbourhood by a peculiar, and to all persons but himself, seemingly ridiculous propensity of making expensive excavations under the earth. In the pursuit of this propensity he has spent large sums of money. He seemed anxious to… [find] employment for the poor, digging holes one day, and filling them up the next…

Amidst all his eccentricities and mole-like propensities, he had some good points in his character, although there was no reckoning, with any certainty, upon what he would do, under any given circumstances… Many whimsical stories are related of him, but we know not on what authority they rest.

Ah, whimsical stories: the problem for biographers is that almost all roads into Williamson’s life and anecdotes about him lead to one man: James Stonehouse (1809–1890). In 1863 he wrote a series of newspaper articles which were then published in book form as Recollections of Old Liverpool by a Nonagenarian – he uses the voice of an old man as a narrative device to tell tales of the city’s history, despite only being in his 50s, and devotes two chapters to Williamson (in 1869, he rehashed much of this material in The Streets of Liverpool). He had supposedly interviewed people who knew Williamson, including some of his many housing tenants, and they had tall tales to tell which form a bewildering mixture of praise for JW’s generosity, bafflement at his eccentricity and horror at his unkempt appearance and poor social skills. Probably some of these are true(ish) – but Stonehouse is very much not a reliable narrator. Almost every account of Williamson written in modern times draws on his stories, so I’m not going to repeat them here.4

He began his career as a journalist, and is known to have fabricated local folklore,5 though in fairness he was also a decent antiquarian, contributing to the Historic Society of Lancashire & Cheshire (HSLC), founded in 1848.

It seems clear Stonehouse never met JW, only settling in the city after the latter’s death (though JS did write a guidebook to the city in 1838), but in 1846 he drafted a document about the ‘King of Edge Hill’ which his later publications stemmed from, and even attempted to map the tunnels. This document was published for the first time6 in 1916 in the Transactions of the HSLC by another Liverpool antiquarian, Charles Robert Hand (1859–1929). Stonehouse gives us an evocative account of the tunnels:

What a strange place is this! Vaulted passages constructed with craftsman-like hands, that run so to speak nowhere, extending some for short, some for long distances, within the limits of the property. Tunnels cut out of the living rock, pits deep, and yawning chasms, wherein the fetid stagnant water throws up miasmatic odours, arches of weighty and solid structure, stable almost as the earth itself. Here the work is finished off as if the mason had laboured hard and toilfully to complete his work in finished pattern, there the moss-grown stone lies in a ponderous fragment as if it had never been moved since the resounding blast shook it from its bed. Here bridged over is a gulf, down which to look makes the head swim and the sense reel…

I think he really did visit them, though his full account clearly smushes together reports from other people too, so yet again the full reality is unclear.

But let’s finish with those tunnels, the mystery that in some way embodies JW’s madcap brain. I loved my visit. But for a fresh take, written long before TripAdvisor,7 we must turn again to Charles Hand, who knew them well. He recalled some early urbex in his youth:

As a lad I, with a number of companions, made them the object of an almost regular Saturday afternoon expedition. Tied together, in single file, and carrying as many lighted candles as we could get, while the last one of the party always held a ball of string which he unwound as we proceeded on our way, the other end of the string having been securely fastened to a large stone which lay by the entrance, we traversed these strange and wonderful passages, literally in “fear and trembling,” afraid yet fascinated by the eeriness of it all, dreading we knew not what, yet going on. Our approach into these mysterious workings was always from what was known as the Great Tunnel, directly under the garden at the back of Mr. Williamson’s house; and probably the knowledge that we were trespassing and had no right to be where we were, imparted piquancy to the adventure. Not until the present year had I the privilege of inspecting the works from their inventor’s own house. Now, of course, I look upon them with entirely different eyes.

Here’s what those different eyes saw in the autumn of 1926, when Charles Hand led a tour for members of the HSLC:8

Armed with electric torches, acetylene lamps and candles, we descended with infinite care the stone steps leading into the very bowels of the earth. At the bottom of the first flight, an archway cut out of the moist and musty rock led away to the right, and the next flight branched away on either hand, giving access to low tunnels and more steps down… The roofs are supported by groined arches of perfect workmanship, but their design is without set idea, and all appear to be entirely useless.

We groped our way carefully along the accessible ramifications of these crypts to the depth of three storeys below the street level. There are three or more storeys below these – the basement is said to be as deep as the buildings are high – but accumulations of rubbish deposited here by generations of builders remodelling the premises for various uses have choked up the lowest catacombs.

We failed to discover a boundary. We were in a nightmare maze of constructed tunnels and caves. Nobody knows their extent. An adventurous youth who had followed the party offered to crawl on hands and knees along one of the tunnels. He stumbled and splashed for a great distance until we could hardly see the candle he pushed before him, but he was beaten at last, there not being room for him between the top of the rubbish and the roof of the tunnel.

A Liverpool Daily Post report on one of Hand’s visits noted that Joseph Williamson “left two puzzles behind him, one for psychologists and one for antiquaries”. The puzzles remain to this day!

This geological study argues that they are very much quarries and not really tunnels at all, in fact.

As if this saga needed yet more eccentricity… those two charities have been rivals of a kind for the last few decades. Both of them run tours, but of different parts of the network, thanks to the complexities of past land ownership. I had a great tour from the Williamson Tunnels Heritage Centre, but the rather slicker Friends of Williamson’s Tunnels have a very informative website (which has almost the same URL, and the whole scenario comes across like something out of Monty Python’s Life of Brian).

I find this unlikely (though some claim his wife was the cultist): they were married in St Thomas’s church, worshipped there (there are records of him paying for a private pew) and were buried there – hardly the signs of a wacky nonconformist.

You can read the Recollections online for yourself if you’re curious. OK, one famous story tells of a banquet JW held where he invited local grandees and served them porridge (another version says beans and bacon). When some guests were offended and stormed off, JW then took his loyal friends to another room for a sumptuous feast. To me this sounds suspiciously like a borrowing from Shakespeare’s Timon of Athens.

Publication in the 1840s had been prevented by the threat of legal action by JW’s friend the artist Cornelius Henderson.

Hand’s writings and much else besides can be found at the HSLC website.

Great article, I have seen documentaries about the tunnels and you have reminded me to add it to my long list of places still to visit.

I really dig this story. I love the Charles Hand/ball of string account. Wonderful period anecdotes, too. Surely a local caving society could be persuaded to map the tunnels? Amazing piece, thank you!