The real Oliver Twist? 1798

A workhouse tale

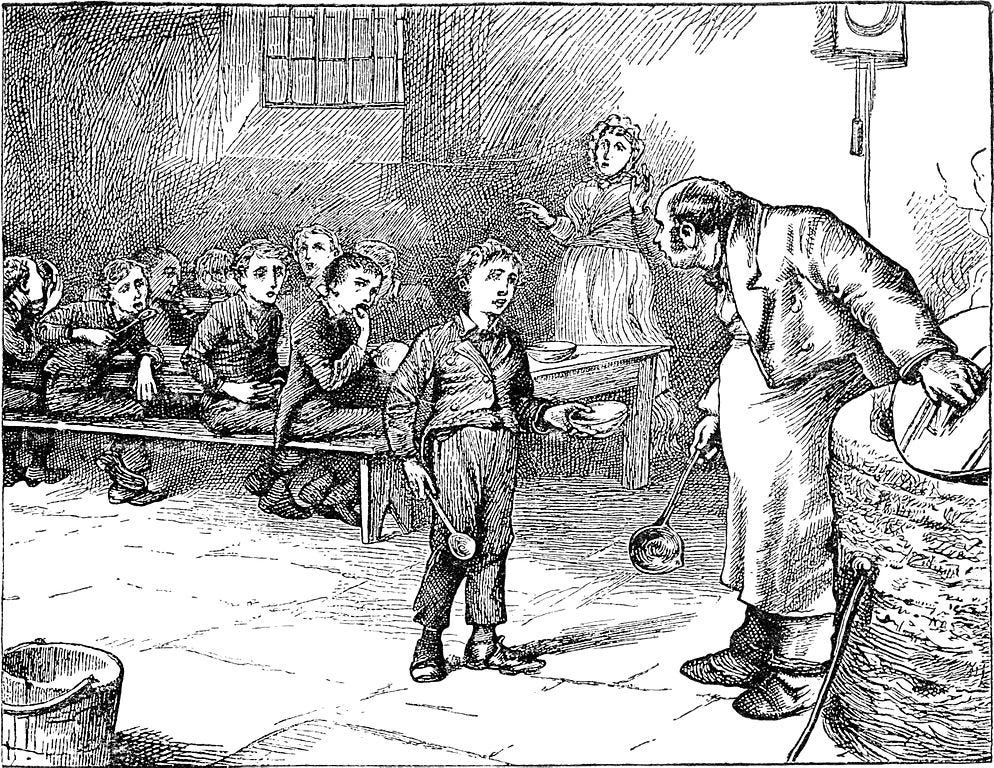

He would gladly have exchanged situations with the poorest of the poor children, whom, from the upper windows of the workhouse, he had seen begging from door to door…

This week I embarked on another journey into London history on foot – you can follow it here – on the theme of St Pancras, an early fourth century martyr whose name is commemorated to this day across several countries; its prevalence in southern England, especially London, had particularly caught my eye. And seeing as 12 May is St Pancras’s Day, well… off I went.

On my route I happened to pass St Pancras Hospital, which incorporates numerous buildings on the site which originally formed the St Pancras Workhouse. And on looking into that, I came across the story of one of its inmates (albeit at an earlier nearby site), which is what I’ll share with you here.

That man was Robert Blincoe (c.1792–1860), who was an orphan sent to that workhouse at the age of four. He stayed there until he was seven, when he and numerous other children were whisked off to undertake brutal labour in a cotton mill near Nottingham.

Long after this, in 1822, by which time his fortunes had improved being married and running his own cotton-spinning business, he met a journalist by the name of John Brown, who hailed from Bolton and was familiar with the Lancashire cotton industry. Brown undertook to record Blincoe’s life story. Sadly Brown’s own career was failing in London, and he committed suicide there, in either 1826 or 1829. The memoir was initially published in 1828 by pressman Richard Carlile, who was already known for supporting radical journalism. He printed Blincoe’s dictated memoir in a five-part series in his magazine The Lion, which campaigned against child labour. Then, four years later, the manuscript was unearthed in a pawn shop and was published by Manchester-based union organiser John Doherty as a short book, A Memoir of Robert Blincoe (subtitle “an orphan boy sent from the workhouse of St. Pancras, London, at seven years of age to endure the horrors of a cotton mill”). This caught popular attention, was quoted in Parliament, and Blincoe himself gave evidence to the 1833 Royal Commission on Employment of Children in Factories1 which led to the Factory Act of the same year.

In 2005, US-based historian of medicine John Waller wrote a book about Blincoe and Brown called The Real Oliver Twist (Icon Books). In it, he uses Blincoe’s life to tell a bigger story of orphans’ lives in the era, and he particularly supports an earlier claim that Blincoe was a key inspiration for Charles Dickens’s famous character. A Guardian article about this by Blincoe’s 3x-great-grandfather, novelist Nicholas Blincoe, provides interesting context and more on the family history. As you will read below, it seems even ‘Blincoe’ was not necessarily his real surname.

Here, then, are extracts of Blincoe’s account2 about the St Pancras workhouse (not the far grimmer tales from Nottingham), as told to John Brown.

Robert Blincoe commenced his melancholy narrative, by stating, that he was a parish orphan, and knew not either his father or mother. From the age of four years, he says, “till I had completed my seventh, I was supported in Saint Pancras poorhouse, near London.” In very pathetic terms, he frequently censured and regretted the remissness of the parish officers, who, when they received him into the workhouse, had, as he seemed to believe, neglected to make any entry, or, at least, any to which he could obtain access, of his mother’s and father’s name, occupation, age, or residence. Blincoe argued, and plausibly too, that those officers would not have received him, if his mother had not proved her settlement; and he considered it inhuman in the extreme, either to neglect to record the names of his parents, or, if recorded, to refuse to give him that information, which, after his attaining his freedom, he had requested at their hands…

In one of our early interviews, tears trickling down his pallid cheeks, and his voice tremulous and faltering, Blincoe said, “I am worse off than a child reared in the Foundling Hospital. Those orphans have a name given them by the heads of that institution, at the time of baptism, to which they are legally entitled. But I have no name I can call my own.”

He said he perfectly recollected riding in a coach to the workhouse, accompanied by some female, that he did not however think this female was his mother, for he had not the least consciousness of having felt either sorrow or uneasiness at being separated from her, as he very naturally supposed he should have felt, if that person had been his mother…

It seems, young as he was, he often enquired of the nurses, when the parents and relations of other children came to see his young associates, why no one came to him, and used to weep, when he was told, that no one had ever owned him, after his being placed in that house. Some of the nurses stated, that a female, who called soon after his arrival, inquired for him by the name of “Saint;” and, when he was produced, gave him a penny-piece, and told him his mother was dead…

Of the few adventures of Robert Blincoe, during his residence in old Saint Pancras workhouse, the principal occurred when he had been there about two years. He acknowledges he was well fed, decently clad, and comfortably lodged, and not at all overdone, as regarded work; yet, with all these blessings in possession, this destitute child grew melancholy. He relished none of the humble comforts he enjoyed. It was liberty he wanted. The busy world lay outside the workhouse gates, and those he was seldom, if ever permitted to pass. He was cooped up in a gloomy, though liberal sort of a prison-house… The aged were commonly petulant and miserable—the young demoralized and wholly destitute of gaiety of heart…

Like a bird newly caged, that flutters from side to side, and foolishly beats its wings against its prison walls, in hope of obtaining its liberty, so young Blincoe, weary of confinement and resolved, if possible to be free, often watched the outer gates of the house, in the hope, that some favourable opportunity might facilitate his escape. He wistfully measured the height of the wall, and found it too lofty for him to scale, and too well guarded were the gates to admit of his egress unnoticed. His spirits, he says, which were naturally lively and buoyant, sank under this vehement longing after liberty. His appetite declined, and he wholly forsook his usual sports and comrades…

Blincoe declares, he was so weary of confinement, he would gladly have exchanged situations with the poorest of the poor children, whom, from the upper windows of the workhouse, he had seen begging from door to door, or, as a subterfuge, offering matches for sale. Even the melancholy note of the sweep-boy, whom, long before day, and in the depths of winter, in frost, in snow, in rain, in sleet, he heard pacing behind his surly master, had no terrors for him…

From this state of early misanthropy, young Blincoe was suddenly diverted, by a rumour, that filled many a heart among his comrades with terror, viz. that a day was appointed, when the master-sweeps of the metropolis were to come and select such a number of boys as apprentices, till they attained the age of 21 years, as they might deign to take into their sable fraternity. These tidings, that struck damp to the heart of the other boys, sounded like heavenly music to the ears of young Blincoe:—he anxiously inquired of the nurses if the news were true, and if so, what chance there was of his being one of the elect. The ancient matrons, amazed at the boy’s temerity and folly, told him how bitterly he would rue the day that should consign him to that wretched employment, and bade him pray earnestly to God to protect him from such a destiny…

Although at this time he was a fine grown boy, being fearful he might be deemed too low in stature, he accustomed himself to walk in an erect posture, and went almost a tip-toe;—by a ludicrous conceit, he used to hang by the hands to the rafters and balustrades, supposing that an exercise, which could only lengthen his arms, would produce the same effect on his legs and body. In this course of training for the contingent honour of being chosen by the master-sweeps, as one fit for their use,—with a perseverance truly admirable, his tender age considered, young Blincoe continued till the important day arrived.

The boys were brought forth, many of them in tears, and all except Blincoe, very sorrowful. Amongst them, by an act unauthorised by his guardians, young Blincoe contrived to intrude his person. His deportment formed a striking contrast to that of all his comrades; his seemed unusually high: he smiled as the grim looking fellows approached him; held his head as high as he could, and, by every little artifice in his power, strove to attract their notice, and obtain the honour of their preference… Boy after boy was taken, in preference to Blincoe, who was often handled, examined, and rejected. At the close of the show, the number required was elected, and Blincoe was not among them! He declared, that his chagrin was inexpressible, when his failure was apparent.

Some of the sweeps complimented him for his spirit, and, to console him, said, if he made a good use of his time, and contrived to grow a head taller, he might do very well for a fag, at the end of a couple of years. This disappointment gave a severe blow to the aspiring ambition of young Blincoe… At night, as Blincoe lay tossing about, unable to sleep, because he had been rejected, his unhappy associates were weeping and wailing, because they had been accepted!

… During Blincoe’s abode at St. Pancras, he was inoculated at the Small Pox Hospital.3 He retained a vivid remembrance of the copious doses of salts he had to swallow, and that his heart heaved, and his hand shook as the nauseous potion approached his lips. The old nurse seemed to consider such conduct as being wholly unbecoming a pauper child; and chiding young Blincoe, told him, he ought to “lick his lips,” and say thank you, for the good and wholesome medicine provided for him at the public expense; at the same time, very coarsely reminding him of the care that was taken to save him from an untimely death by catching the small-pox in the natural way. In the midst of his subsequent afflictions, in Litton Mill, Blincoe, declared, he often lamented having, by this inoculation, lost a chance of escaping by an early death, the horrible destiny for which he was preserved.

From the period of Blincoe’s disappointment, in being rejected by the sweeps, a sudden calm seems to have succeeded, which lasted till a rumour ran through the house, that a treaty was on foot between the Churchwardens and Overseers of St. Pancras, and the owner of a great cotton factory, in the vicinity of Nottingham, for the disposal of a large number of children, as apprentices, till they become twenty-one years of age. This occurred about a twelvemonth after his chimney-sweep miscarriage. The rumour itself inspired Blincoe with new life and spirits; he was in a manner intoxicated with joy, when he found, it was not only confirmed, but that the number required was so considerable, that it would take off the greater part of the children in the house,—poor infatuated boy! delighted with the hope of obtaining a greater degree of liberty than he was allowed in the workhouse,—he dreamed not of the misery that impended, in the midst of which he could look back to Pancras as to an Elysium, and bitterly reproach himself for his ingratitude and folly.

Blincoe’s time in Nottingham was indeed far harsher, where the children (a “pale, lean, sallow-looking multitude”) had to work in meagre clothes “destitute of shoes and stockings”. We learn “from morning till night, he was continually being beaten, pulled by the hair of his head, kicked or cursed”, and everyone was “half-starved”.

On eventually leaving as a young adult, he worked as a cotton dealer and hired a warehouse as his business grew. Alas in 1824 a new premises, with the latest cotton-spinning machinery, burnt to the ground and he vowed to abandon the trade forever. Now destitute, he spent a time in Lancaster Castle prison, but did return to the cotton trade after all, and ultimately he and his new family thrived.

St Pancras Workhouse, redeveloped nearby in 1809 and again in the 1890s, does seem to have been better than many of its era – although in the 1850s it was investigated for insanitary, overcrowded conditions.

London Smallpox Hospital was on the site of what is now St Pancras railway station.

A very interesting story. One significant thing to respect in the history of Robert Blincoe's life is that now all those who read the article are informed about this man and the time in which he lived --- more than the name he was assigned. Thank you for this excellent and fascinating piece. I knew nothing of the St Pancras Workhouse, smallpox prevention by swallowing salts, the gathering up of orphans for apprentices by chimney sweeps and factory owners (a sad aspect of life in 1800s England). A side topic is comparing types of debt today and their consequences....but I have rambled on too long!

Really enjoyed this piece.