The real Mr Fogg, 1870

An inspiration for a famous tale

In a few minutes I was on deck, and no one, unless he has been for twenty-five days without seeing land or even a sail, can appreciate our delight as we gazed on the scene…

This year will see the 150th anniversary of the first publication, in serial form, of Jules Verne’s classic adventure narrative, Around the World in Eighty Days, and there has already been a new TV adaptation. When this newsletter goes out, I will (hopefully!) have just finished my own little homage to the voyage, ‘Around the World in Eight Hours’, in which I walk more than 20 miles across central London against the clock, visiting places which in some way represent or relate to every country visited by Phileas Fogg in the original and unearthing some interesting corners of history in the process. You can follow my misadventures on Twitter here or through the hashtag #londonfogg.

I say ‘in the original’, but Jules Verne can hardly claim to have invented the core idea of the journey – you can read about the various apparent influences in more detail here, but several people in his era had tried using the then relatively new technologies of railways and steamships to circumnavigate the globe against the clock. One of them was the American businessman and presidential hopeful George Francis Train, who made a real 80-day world trip in 1870. The pioneering travel agency firm Thomas Cook & Son organised a round-the-world tour in 1872. But this week in Histories I give you a snapshot of the adventures of William Perry Fogg (1826–1909). Yes, Fogg.

The real Mr Fogg was born in New Hampshire in the United States and then moved to Cleveland, Ohio, where he became a pillar of the community, selling china, supporting descendants of New England pioneers and helping to run the city. In 1868, however, wanderlust took over and he set off on the first of his travels. Initially he visited every state in the US (at that point there were 37 of them), Canada and the West Indies, before becoming more ambitious. His trip to Japan in 1870 is believed to have been one of the first by an American. Over the next two years he wrote a series of letters, mostly published in the Cleveland Leader newspaper (and then as a book in May 1872), with others using the pseudonym Nebula in the Cleveland Daily Herald. In the preface to his book,1 Fogg writes:

My motive was not merely the pursuit of pleasure, but the desire to gratify a long-cherished passion to see once in my lifetime the strange and curious nations of the Orient, books of travel among whom have always had for me a strange fascination.

William Perry Fogg visited many of the places that his fictional counterpart did, although generally in the opposite direction: Phileas went by train from San Francisco through Salt Lake City, but William the other way; before that, Phileas went from India to China and Japan, but William again the opposite. And like Phileas, William used the Suez Canal – which had opened not long beforehand, in 1869 – but again in the other direction, heading to Egypt.

Although Jules Verne provides some narratorial details of the places his protagonist visited, sometimes seen through manservant Passepartout’s eyes, Phileas Fogg himself was a self-contained character with little interest in the places he passed through:

Always the same impassible member of the Reform Club, whom no incident could surprise, as unvarying as the ship’s chronometers, and seldom having the curiosity even to go upon the deck, he passed through the memorable scenes of the Red Sea with cold indifference…

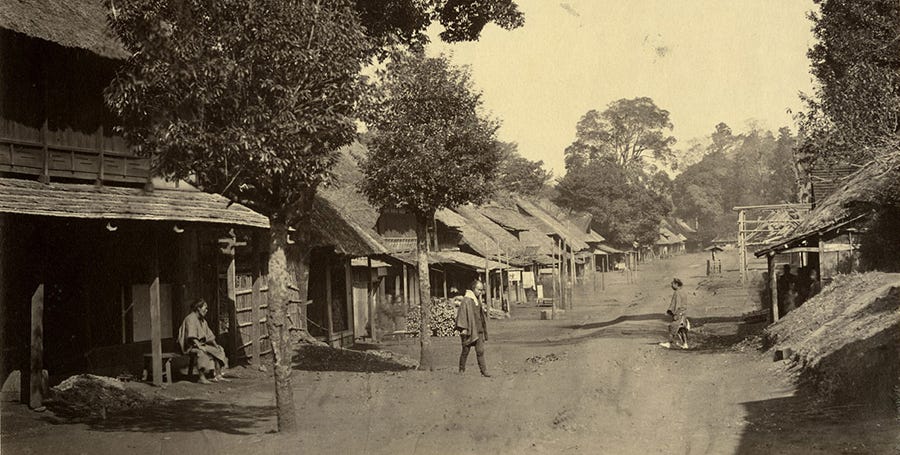

The real Mr Fogg, however, took much more interest, as a few selections below demonstrate, in which he describes the ship, the terrors of a cyclone, and his first arrival in Japan. The picture of a Japanese village below was used in his book.2

21st November 1870 [Letter IV]

The great disparity of surface on this globe between land and water is forced upon our minds by the thought that we have now for twenty-one days a been pushing steadily westward over the vast desert of waters, and have seen neither land nor sail. Day after day is the same dreary expanse, and daring the twenty-five days from San Francisco to Japan it is rarely that a vessel of any kind is seen… Night and day there has been no cessation of the steady clang of the machinery, the quiver and crackling of the immense steamer, as she pushes westward ten miles an hour, never varying from her course, and regardless alike of wind or storm. We have seen old Ocean in all his moods—for days smooth and glassy, reflecting the bright sun and cloudless sky with scarcely a ripple, reminding me of Lake Erie in midsummer. Then gathering clouds and the angry waves lashed into fury, tossing our huge ship to and fro like a cockle shell…

I had read of this Pacific mail line as unequaled in the world in size of ships, completeness of appointments, and comfort to passengers, but I was unprepared for such a floating palace as the “America” proves to be. If there can anywhere be comfort or even pleasure in a sea voyage, it is here… The table is supplied with every delicacy of a first class hotel. Vegetables and fruits, either fresh or canned beef, mutton and poultry, were shipped, “on the hoof,” before leaving port, and the steward is saving the fattest of turkeys for our Thanksgiving dinner…

On Monday, 14th of November, we passed the 180th meridian from Greenwich, and were just half round the world from London. At this time my watch set in Cleveland was eight hours too fast, and when the dinner gong sounded at five o’clock, it was one o’clock at night in Cleveland and five A. M. in England… In a few days we shall eat our five o’clock Thanksgiving dinner long before daylight on the lake shore, and my Christmas at Shanghai will be thirteen and a half hours ahead of Cleveland. The day lost is past recovery to us who go on round the world, but it will be picked up by the steamer on her return…3

24th November [Letter V]

On Monday night we were within eight hundred miles of Yokohama, in the edge of that current of warm water which corresponds with the “Gulf Stream” of the Atlantic here as there the fruitful source of typhoons, cyclones and hurricanes… The day had been warm and sultry, with occasional showers, but the barometer had indicated no storm brewing, until at ten o’clock it dropped in forty minutes from 29-80 to 28-68. So sudden a fall boded us no good, and our vigilant captain at once prepared for one of those terrific storms… peculiar to the east coast of Asia, and the dread of all navigators in these waters.

Within less than an hour from the first premonition it struck the ship, the tremendous force of the wind throwing her instantly almost upon her beam ends. I had retired early and was rudely awakened by being pitched out of my berth, and with trunk and other loose articles, shot over to the lee side of my state room. Fortunately the room was small so that I did not have far to go. Hastily dressing I managed with some difficulty to open the door leading to the main saloon, and there the sight was truly appalling. The skylights had all been dashed in, chairs and everything moveable were sweeping to and fro across the room, the floor was covered with broken glass from the racks over the tables, the lamps were all extinguished, the howling of the wind and dashing of the rain and spray through the open sky lights, the lurid glare of the lightning which seemed one incessant flash, made up the most frightful scene I ever witnessed. But more startling than all this were the shrieks of some of the ladies who had rushed half-clad from their rooms, and losing all presence of mind at every lurch of the ship uttered most heart-rending screams.

My experience of storms off Cape Hatteras, and in the Gulf of Mexico, was nothing compared with a typhoon in the Chinese sea. Every few minutes a heavy wave would strike the ship, dash the water over the top of the cabins, and as it thundered against the guards our staunch vessel would quiver and tremble as if going to pieces…

But she was very strongly built, and having one thousand tons less coal on board than when she left San Francisco was very buoyant; her machinery was strong, and her officers all thorough seamen. Every man was at his post, and when Captain Doane came down and spoke a few cheerful words to the affrighted passengers the panic subsided…

The next morning the sun shone bright and clear, and as we gathered in the saloon to a late breakfast we were a hard looking set. Everybody shook hands with everybody else, and each had his or her personal experience to relate. The events of the night before seemed like a horrible dream. But the bruises some of us had received, the heads of some of the waiters cut in falling against tables and over chairs, the smashed bulwarks and battered guards, and the stains of the salt spray to the very top of the smokestack, were evidence that our experience of a typhoon had been real. The captain said that in his twenty-three years’ experience he had never seen a harder blow, although fortunately for us it was of short duration…

To-day is Thanksgiving, and to us it is an occasion of genuine heartfelt thanksgiving and gratitude to Almighty God for the dangers we have escaped, and we need no fat turkeys nor sparkling champagne to give fervor to our thanks.

1st December [Letter VI]

Yokohama, Japan

On the morning of the 25th of November I was awakened by a rapping at the door of my room on the America, and recognized the voice of my friend, the Consul at Swatow, saying, “Come out and see Japan; it is in plain sight, right before us.” In a few minutes I was on deck, and no one, unless he has been for twenty-five days without seeing land or even a sail, can appreciate our delight as we gazed on the scene. We were approaching the entrance of the Bay of Yeddo, which very much resembles the “Narrows” at New York. The high wooded hills in front were dotted with small houses, looking very cosy, surrounded with evergreens and fruit trees; on our left were several conical-shaped mountains rising out of the water, some of which were extinct volcanoes; all around us were fleets of junks and fishing boats, manned by a strange race, dark-skinned, bare-headed, with no superabundance of clothing, who watched our steamer as she glided by with even greater curiosity than we looked at their queer craft, outlandish and clumsy as if modeled from Noah’s Ark. The sun was not yet above the horizon; but, through an occasional rift in the clouds which obscured Fu[j]iyama, we could see the gilding of the snow-covered cone of this “Matchless Mountain,” which forms the background of every Japanese landscape. Attracted by so many strange sights we lingered on deck even after the gong had called us to our last meal on the ship, for at eleven o’clock we expected to reach Yokohama, twenty miles up this beautiful bay.

Trunks are packed and baggage put in order for shore, stovepipe hats replace the wideawakes and Scotch caps, which have seen service on ship board, and after breakfast all are gathered on the upper deck as we pass the light ship and carefully thread our way through the fleet of foreign ships anchored in front of the city. Besides the eight war vessels, two, each, of French, American, British and German, there are now in this port over fifty sailing ships and fifteen steamers, representing every maritime nation in the world. The gun is fired, the anchor dropped, and the wheels stop for the first time since leaving San Francisco.

Fogg’s first book, Letters from Japan, China, India, and Egypt, brings together his newspaper letters, with the addition of photographs; in 1875 he also published Travels and Adventures in Arabistan, or The Land of the Arabian Nights, recounting further travels through the Middle East from a journey which began in January 1874. The most detailed biography I can find of him is here.

It was taken by Felice Beato a few years earlier.

William clearly understood datelines better than Phileas, who nearly lost his wager due to his oversight on this theme.