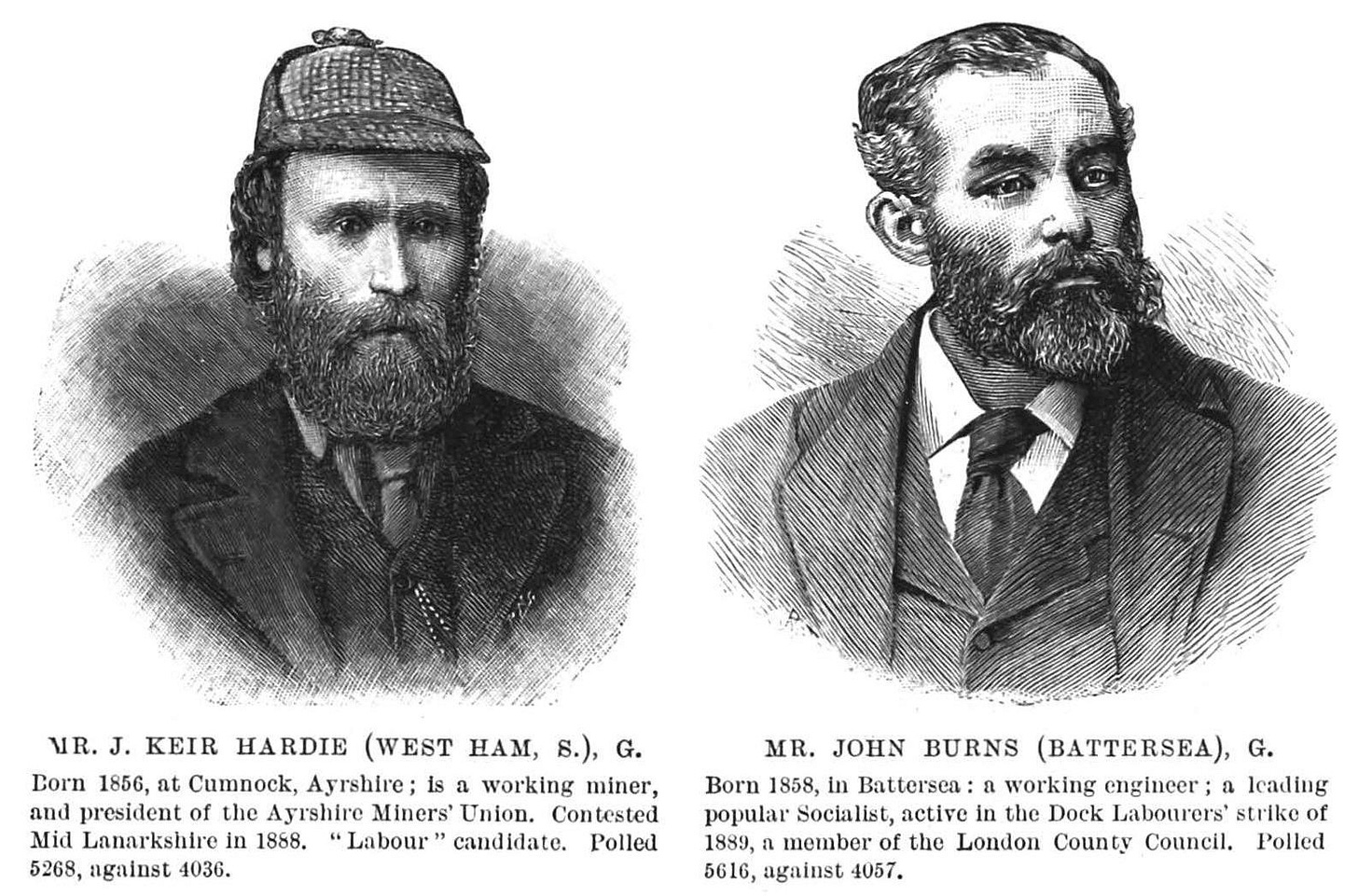

The man in the cloth cap, 1892

The first Labour Kier sets the record straight

A short piece this week – in this crucial year for democracy in the UK, USA and France, the election results came out this morning here in Britain, and we’re all a bit tired. But as we have a new prime minister, Sir Keir Starmer, let’s go back and meet the man he is believed to have been named after.

James Keir Hardie (1856–1915) was born (as James Kerr, before his mother remarried ship’s carpenter David Hardie) into the coalmining town of Newhouse, Lanarkshire, Scotland, and went into the pits himself aged only 10. His vocal skills meant that the self-educated Keir was soon chosen to represent the miners through trade unions, and he led strikes in the 1880s. And this, in turn, led him to politics – and a firm belief that working-class people needed their own party (at a time when the main choices were Conservative & Liberal Unionist or Liberal). He stood as an independent candidate in the 1888 by-election in Mid-Lanark, and although he didn’t win, he was motivated to form the Scottish Labour Party. In 1892, he was elected for the first time as an ‘independent Labour candidate’ at West Ham in London, although he lost his seat in 1895. And in 1900 he was elected at Merthyr Tydfil in Wales and was instrumental in the founding of the Labour Party proper, which he later led for a couple of years. (Britain would have to wait until 1929 for its first Labour prime minister, Ramsay MacDonald, and Keir Starmer is only the seventh Labour candidate to reach this height.)

But in many ways that 1892 success was the breakthrough. The story goes that at his election in 1892, Hardie was driven to Westminster in triumph by his supporters, accompanied by a brass band. He entered Parliament wearing a tweed suit, red tie and workman’s cap and became known as “the man in the cloth cap” (although the Dictionary of National Biography says it was more like a deerstalker, rather confirmed by the illustration below) – and supposedly this caused outrage. But many years later – in April 1914 – Hardie wrote a letter to the Manchester Guardian (The Guardian since 1959) to clear up some myths from that momentous day, so here it is…

Sir,—I am sorry to destroy two well-worn myths, and it only respect for your always excellent “Miscellany” which impels me to attempt to do on.

The ‘brass band’ of which so much has been heard in connection with my first entry to the House of Commons in 1892, and of which I have seen pictorial illustrations including the big drum, consisted of one solitary cornet. The facts are these. The dockers of West Ham had decided that I should go to Parliament in a “coach” like other MPs, and had actually raised money for the purpose. When, however, I declined their offer they resolved to have a “beano” on their own. Whereupon they hired a large-sized waggonette to drive to Westminster in, from which to give me a cheer as I entered the gates, and, good honest souls, invited me to a seat therein. Only a churl could have said them nay. The cornet-player “did himself proud” on the way up from Canning Town, and the occupants of the brake cheered lustily as I was crossing Palace Yard. The cornet may also have been used, though I cannot now for certain recall.

The incident was no scheme of mine – in fact, I knew nothing about the arrangements till asked to occupy a seat. It was the outcome of the enthusiasm, and warm-hearted enthusiasm, of my supporters, for which I honoured them then, even as I do now. So much for the “brass band.”

The statement that I perambulated the floor of the House in my offensive cap until recalled to orderliness by the “awful tones” of Mr Speaker Peel is without any foundation in fact. I was walking up the floor to take the oath in conversation with Sir Charles Cameron, then one of the members for the city of Glasgow, who, with hands plunged deep in his trousers pockets, was wearing his hat. He did not realize that it was against him that the Speaker’s call was directed until I called his attention to the fact that he was wearing his hat, which he at once removed.

It sufficed for some of the more imaginative gentlemen in the Press Gallery that I was there, and next day there were long descriptions of the “truculent” way in which I had defied the conventions and of the stern rebuke which Mr Speaker administered. All pure fiction! In fact, Mr Speaker Peel himself, in his own room next day, expressed to me personally his surprise and regret at the injustice which the press had done.

For 23 years these fictions have done duty in all parts of the world, and it is too much probably even to hope that this correction will lay them to rest. May I add that the House could not very well have “grown accustomed” to John Burns’s bowler hat in 1892,1 since he and I were returned that year for the first time?—Yours, &c.

House of Commons. J. Keir Hardie.

Hardie hasn’t gone down in history as a great MP as such, but there’s no doubting his convictions in fighting for the underdog – in later years he campaigned fiercely for women to have the vote (Sylvia Pankhurst called him “the greatest human being of our time” when he died), for black rights in South Africa, for self-rule in India, and against World War One.

Hardie here refers to his fellow radical MP (though not with Labour), John Burns, known for his straw hats and bowlers.