'The fixed vision of a monomaniac', 1940

'Drums, flags and loyalty-parades'… plus ça change.

Let’s be clear from the start: this is in no way a celebration. But today, 18th July, is the centenary of the original publication of Mein Kampf by Adolf Hitler. I was interested to see how it was received in the English-speaking world, though it doesn’t seem to have particularly caught much attention for several years. It was begun while he was in prison for his attempt to seize power in the Munich Putsch of 1923 and is a mixture of autobiography and manifesto, running to nearly 800 pages, setting out his belief in a Jewish conspiracy to run the world (based on an infamous hoax that I’m not even going to name here). This was also an early statement of his view that ‘the weak’ would be better off dead than being protected, and he suggested that Germany needed Lebensraum (‘living space’) by expanding into territories to the east. I don’t think any of us need more detail than that.

Looking in the British Newspaper Archive, the earliest reference I can find to it in the UK dates from December 1930 in the Saturday Review of Politics, Literature, Science and Art, and it’s only a passing mention in an article titled ‘Hitler’s foreign policy’:

The National Socialist attitude towards Great Britain has not yet been clearly defined, but the following passage in Herr Hitler’s book, ‘Mein Kampf,’ gives an indication of the party leader’s views: “Great Britain does not wish Germany to become a World Power, but France does not want Germany to be a Power of any description. Herein lies an important difference. To-day we do not fight for world power, but for the unification and existence of our country and for the daily bread of our children. If this is taken into consideration, then we can only regard two European Powers as our potential allies, Great Britain and Italy.”

Yeah, well, one of them stayed his friend (not that Britain didn’t come quite close to it).

A snippet in the West Lothian Courier of 19th May 1933 says Mein Kampf “is to be published in this country immediately. The English rights of Germany’s ‘Best Seller’ have been the subject of the keenest competition among publishers for weeks past” – the ‘winners’ being a firm called Hurst and Blackett. This was only two years after the reporter notes that Hitler’s book “was being hawked round Europe but could not find a publisher”.1

For context, Hitler became the leader of the National Socialist German Workers Party in 1921, but in 1925 still had little profile outside his own country. By early 1933, he was the country’s chancellor, and suddenly of much more interest.

In fact four different English translations of Mein Kampf were made before the Second World War but the first (from Hurst and Blackett), My Struggle, didn’t appear until October 1933, and it was an abridged version (allegedly pruned by Nazi officials) – though the London Times printed some extracts in July, saying English readers “will find it more illuminating as a psychological revelation” but also rather alarmingly invited them “to compare promise with performance”. A US version of the same edition was titled My Battle.2 The first unexpurgated edition came out in 1939. Each edition sold all too well: more than 15,000 of that first one, and five years later (when Hitler was openly persecuting Jews), more than 50,000. Book reviews certainly came thick and fast that October on both sides of the Atlantic, although tended to avoid strong comments. Even the Guardian saw it as a “noteworthy personal and political document” and grumbled primarily about the translation and abridgement.

American firm Stackpole Books produced an edition in February 1939, upon which Frances Stackpole, wife of the boss, later observed: “When I read the first chapters of Mein Kampf in the New York Public Library one morning before I went out to lunch, I remember running down the long flight of steps to Fifth Avenue and reaching the curb just in time to vomit. I have since considered that the definitive review of the book.”

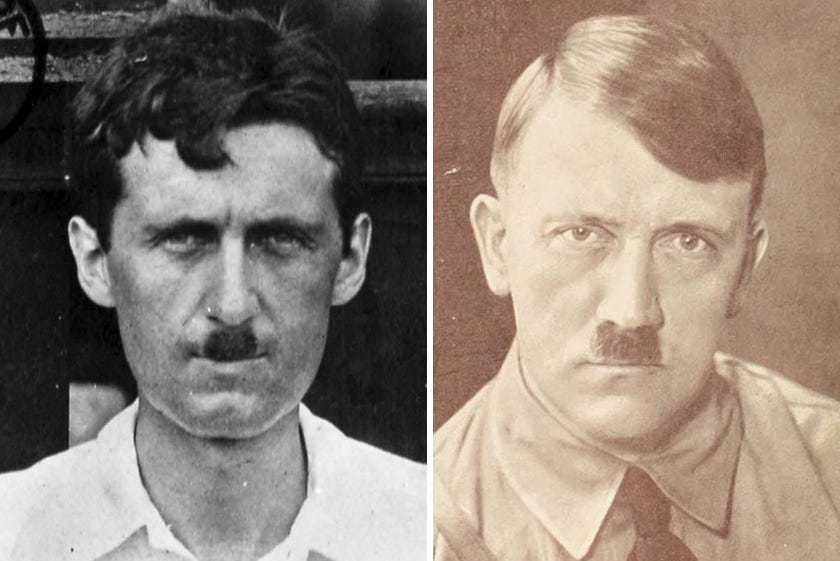

It’s tempting to stop with that. But instead I’ll give you perhaps one of the more well-known reviewers of the first full edition that the original English publisher brought out: George Orwell. The text below was published in the New English Weekly on March 21st 1940, by which time Britain and Germany were at war. This was four years before Animal Farm came out and eight before Nineteen Eighty-Four. It’s as much an attempt to understand why people fall for charismatic but totalitarian, self-serving leaders as it is a book review. Make of this what you will.

It is a sign of the speed at which events are moving that Hurst and Blackett’s unexpurgated edition of Mein Kampf, published only a year ago, is edited from a pro-Hitler angle. The obvious intention of the translator’s preface and notes is to tone down the book’s ferocity and present Hitler in as kindly a light as possible. For at that date Hitler was still respectable. He had crushed the German labour movement, and for that the property-owning classes were willing to forgive him almost anything. Both Left and Right concurred in the very shallow notion that National Socialism was merely a version of Conservatism.

Then suddenly it turned out that Hitler was not respectable after all. As one result of this, Hurst and Blackett’s edition was reissued in a new jacket explaining that all profits would be devoted to the Red Cross. Nevertheless, simply on the internal evidence of Mein Kampf, it is difficult to believe that any real change has taken place in Hitler’s aims and opinions. When one compares his utterances of a year or so ago with those made fifteen years earlier, a thing that strikes one is the rigidity of his mind, the way in which his world-view doesn’t develop. It is the fixed vision of a monomaniac and not likely to be much affected by the temporary manoeuvres of power politics. Probably, in Hitler’s own mind, the Russo-German Pact represents no more than an alteration of time-table. [This is the 1939 Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact in which the two countries agreed to avoid aggression for 10 years and divided Eastern Europe into separate spheres of influence. Hitler broke the agreement in 1941, so Orwell’s predictions here were correct.] The plan laid down in Mein Kampf was to smash Russia first, with the implied intention of smashing England afterwards. Now, as it has turned out, England has got to be dealt with first, because Russia was the more easily bribed of the two. But Russia’s turn will come when England is out of the picture—that, no doubt, is how Hitler sees it. Whether it will turn out that way is of course a different question.

Suppose that Hitler’s programme could be put into effect. What he envisages, a hundred years hence, is a continuous state of 250 million Germans with plenty of ‘living room’ (i.e. stretching to Afghanistan or thereabouts), a horrible brainless empire in which, essentially, nothing ever happens except the training of young men for war and the endless breeding of fresh cannon-fodder. How was it that he was able to put this monstrous vision across? It is easy to say that at one stage of his career he was financed by the heavy industrialists, who saw in him the man who would smash the Socialists and Communists. They would not have backed him, however, if he had not talked a great movement into existence already. Again, the situation in Germany, with its seven million unemployed, was obviously favourable for demagogues. But Hitler could not have succeeded against his many rivals if it had not been for the attraction of his own personality, which one can feel even in the clumsy writing of Mein Kampf, and which is no doubt overwhelming when one hears his speeches. whelming when one hears his speeches. I should like to put it on record that I have never been able to dislike Hitler. Ever since he came to power—till then, like nearly everyone, I had been deceived into thinking that he did not matter—I have reflected that I would certainly kill him if I could get within reach of him, but that I could feel no personal animosity. The fact is that there is something deeply appealing about him. One feels it again when one sees his photographs—and I recommend especially the photograph at the beginning of Hurst and Blackett’s edition, which shows Hitler in his early Brownshirt days. It is a pathetic, dog-like face, the face of a man suffering under intolerable wrongs. In a rather more manly way it reproduces the expression of innumerable pictures of Christ crucified, and there is little doubt that that is how Hitler sees himself. The initial, personal cause of his grievance against the universe can only be guessed at; but at any rate the grievance is here. He is the martyr, the victim, Prometheus chained to the rock, the self-sacrificing hero who fights single-handed against impossible odds. If he were killing a mouse he would know how to make it seem like a dragon. One feels, as with Napoleon, that he is fighting against destiny, that he can’t win, and yet that he somehow deserves to. The attraction of such a pose is of course enormous; half the films that one sees turn upon some such theme.

Also he has grasped the falsity of the hedonistic attitude to life. Nearly all western thought since the last war, certainly all ‘progressive’ thought, has assumed tacitly that human beings desire nothing beyond ease, security and avoidance of pain. In such a view of life there is no room, for instance, for patriotism and the military virtues. The Socialist who finds his children playing with soldiers is usually upset, but he is never able to think of a substitute for the tin soldiers; tin pacifists somehow won’t do. Hitler, because in his own joyless mind he feels it with exceptional strength, knows that human beings don’t only want comfort, safety, short working-hours, hygiene, birth-control and, in general, common sense; they also, at least intermittently, want struggle and self-sacrifice, not to mention drums, flags and loyalty-parades. However they may be as economic theories, Fascism and Nazism are psychologically far sounder than any hedonistic conception of life. The same is probably true of Stalin’s militarised version of Socialism. All three of the great dictators have enhanced their power by imposing intolerable burdens on their peoples. Whereas Socialism, and even capitalism in a more grudging way, have said to people ‘I offer you a good time,’ Hitler has said to them ‘I offer you struggle, danger and death,’ and as a result a whole nation flings itself at his feet. Perhaps later on they will get sick of it and change their minds, as at the end of the last war. After a few years of slaughter and starvation ‘Greatest happiness of the greatest number’ is a good slogan, but at this moment ‘Better an end with horror than a horror without end’ is a winner. Now that we are fighting against the man who coined it, we ought not to underrate its emotional appeal.

After writing more than 200 of these articles plundering historical documents, in two weeks I’m rebooting them with a revised, slightly shorter format. Watch this space!

As a lighter side note, this was followed by these observations: a publisher “also told me that, for a first novel, it is rarely an author receives more than forty or fifty pounds. This somewhat shatters the belief of those people who seem to think that anyone who has had a book published automatically joins the rank of super-tax payers. It is the booksellers, he said, who take the greatest profit, amounting, in the case of the Colonies, to as much as 50 per cent.” No comment.

I was going to write about Mein Kampf in my "On This Day in History" series on July 18, but I got behind the eight ball that day and didn't make the post. Now I'm really kicking myself because I didn't realize that the publication was a century ago this year–not that the screed deserves celebration.

I'm fascinated by the fact that Hitler ultimately came to power by failing to overthrow the government. Granted, that is a simplified version of the events that led to his ascension of power. But if you were alive at the time and would have read that he had been thrown in jail for his actions, would you have put money on Hitler becoming a world-dominating figure?

Furthermore, did you know that in Nazi Germany, any time a couple got married, they got a copy of Mein Kampf for "free", paid for by the government?

I don't know if I believe that Hitler was a billionaire like I saw in a documentary on the History channel years ago, but by the time he came to power, he wasn't poor. The man knew how to run a racket and keep it quiet.

If the last four paragraphs of this article are Orwell's review, why not put it in a blockquote?