Stupendious antiquity, 1649

"It did as much exceed Stonehenge as a Cathedral does a Parish Church"

Here in the 21st century, it’s hard to capture the excitement of discovery – everything has been seen before, photographed endlessly, shared on Instagram. One of the joys of looking back through history is finding those moments where someone was the first to see something – or, at least, the first to document it properly.

This week I want to share a little vignette of this kind, and its writer was a lively, charming character who I hope to return to another time. And I confess I’m sharing it as it relates to an obsession of mine – the prehistoric sites of ancient Britain – and a new project I have relating to the subject.

Everyone has heard of Stonehenge, of course, and here at Histories we dropped by there to witness the first modern Druid ceremony for the summer solstice, in 1905. But any discerning fan of megaliths will tell you that Avebury, also in Wiltshire, is even better – it’s the largest megalithic stone circle in the world. And the first person to write about it properly was a man called John Aubrey.

I have to say properly because there were a few brief earlier mentions in print (and of course all the local people would have known about the stones since, well, since they were put there).

The man who created the whole concept of antiquarianism was John Leland, who travelled around Britain in the 1530s and 1540s, as well as combing libraries across the land (sadly “he fell beside his wits” and was later certified insane). He wrote this terse note about Avebury:

[The River] Kennet rises in the north-north-west at Silbury Hill bottom, whereby have been camps and sepultures of men of war, as at Abury a mile off, and in diverse places of the plain.

(Side note: historically the village was typically referred to or pronounced as Abury.)1

The next great documenter of British antiquities was William Camden (1551–1623), who didn’t even mention Avebury in his 1586 Britannia, although the 1610 edition did add this:

Within one mile of Silbury is Abury, an uplandish village built in an old Camp, as it seems, but of no large compass, for it is environed with a fair trench and hath four gaps as gates, in two of the which stand huge Stones as jambs, but so rude that they seem rather natural than artificial, of which sort there are some other in the said village. The River Kennet runs at the first Eastward through certain open fields, out of which there stand up aloft everywhere stones like rocks.

But it’s Aubrey who really took note.

And who was he? John Aubrey was a bookish lad born in Wiltshire in 1626 (only 15 miles away from Avebury) to an affluent family. He went on to Oxford to study, although the Civil War rather got in the way; John himself was a Royalist, but not dogmatically so. He began to collect notes on antiquities2 (and contributed to the Royal Society), as well as writing gossipy biographies of renowned figures past and present, which went on to become famous in Victorian times as Brief Lives – but neither of these collections were actually published in his lifetime. The only book that was, Miscellanies, was an anthology of occultism and supernatural phenomena that rather presaged 20th-century interest in these. Above all, he seems to have had something of a butterfly mind, driven by curiosity – both of which make him instantly likeable. (His friend George Ent versified that his “boundlesse mind / Scarce within Learnings compasse is confin’d”.)

So let’s join John now, out on a post-Christmas hunting party in January 1649 at the age of 23 (although he only wrote this up as a reminiscence later – sometime between 1665 and 1693).

I was inclin’d by my Genius from my childhood to the love of antiquities: and my Fate dropt me in a country most suitable for such enquiries.

Salisbury-plaines, and Stonehenge I had known from eight years old: but, I never saw the Country about Marlborough, till Christmas 1648: being then invited to the Lord Francis Seymour’s [a Royalist politican], by the Honorable Mr. Charles Seymour, with whom I had the honor to be intimately acquainted, and whose Friendship I ought to mention with a profound respect to his memory.

The morrow after Twelfday [i.e. Epiphany], Mr. Charles Seymour and Sir William Button [a local landowner], met with their packs of Hounds at the Grey-Wethers. These downs look as if they were sown with great Stones, very thick, and in a dusky evening, they look like a flock of Sheep: from whence it takes its name [i.e. wethers is a country word for sheep]: one might fancy it to have been the scene, where the giants fought with huge stones against the Gods.

’Twas here that our game began, and the chase led us (at length) thorough the village of Aubury, into the closes there: where I was wonderfully surprized at the sight of those vast stones, of which I had never heard before: as also at the mighty Bank and graffe [ditch] about it: I observed in the inclosure some segments of rude circles, made with these stones, whence I concluded, they had been in the old time complete. I left my company a while, entertaining myself with a more delightful indagation [investigation]: and then (steered by the cry of the Hounds) overtooe the company, and went with them to Kennet, where was a good hunting dinner provided.

Our repast was cheerful, which being ended, we remounted, and beat over the downs with our greyhounds. In this afternoon’s diversion I happened to see Wensditch [Wansdyke, another local earthwork], and an old camp and two or three sepulchres. The evening put a period to our sport, and we returned to the Castle at Marlborough, where we were nobly entertained… I think I am the only surviving gentleman of that company.

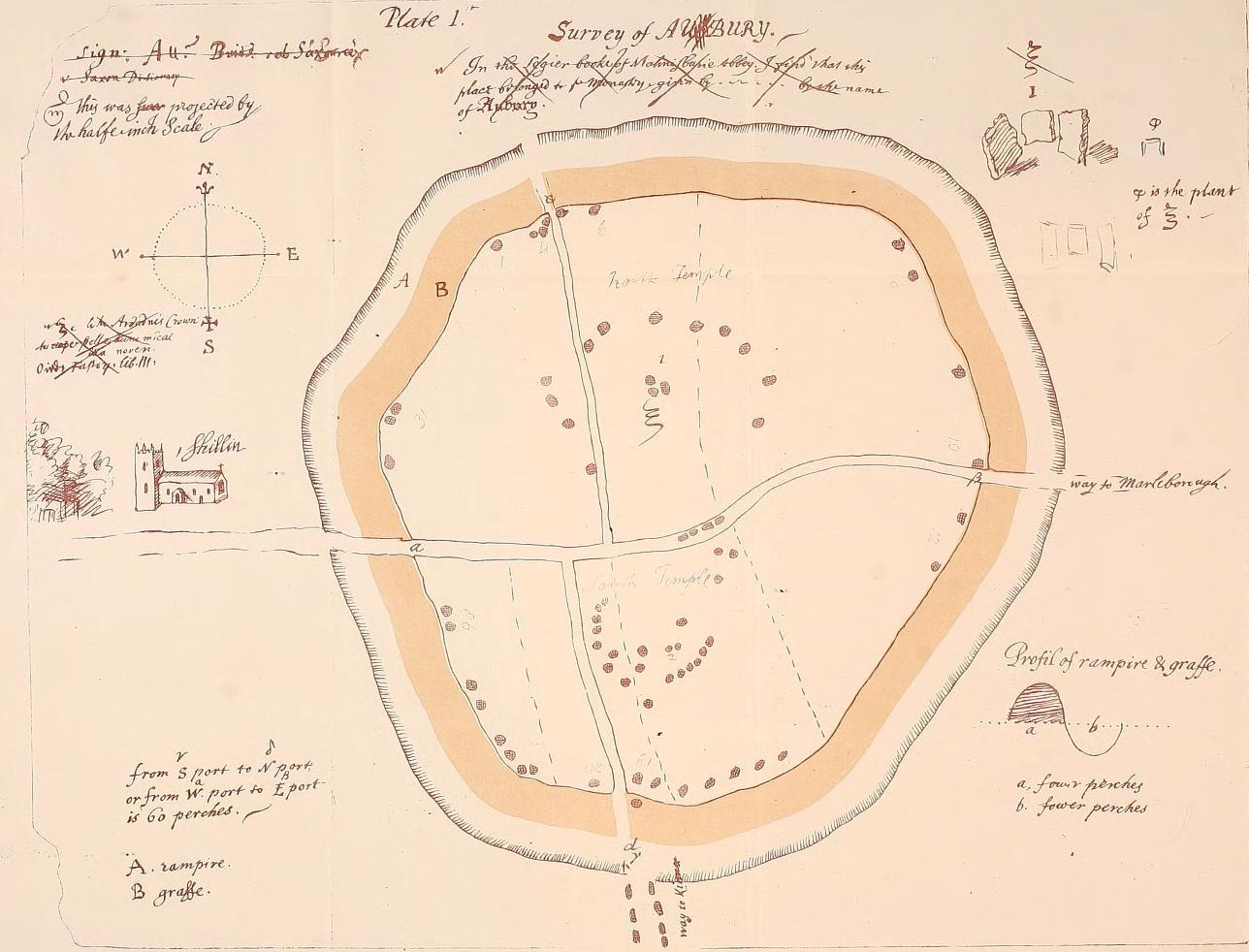

John would return many times to the site, and was the first person ever to survey it in detail. His plan (pictured above) has informed archaeologists ever since, especially as numerous stones have since been lost.

By 1663, he had the ear of the newly restored king, Charles II, who took an interest in Avebury, as John relates:

King Charles II (age 32) discoursing one morning with my Lord Brownker (age 43) [William Brouncker was the first president of the Royal Society] and Dr. Charleton [the king’s physician, who also wrote a book claiming Stonehenge to have been built by the Vikings] concerning Stonehenge, they told his Majesty, what they had heard me say, concerning Aubury, that it did as much exceed Stonehenge as a Cathedral does a Parish Church. His Majesty admired that none of our Chorographers3 had taken notice of it: and commanded Dr. Charlton to bring me to him the next morning. I brought with me a draught of it done by memory only: but well enough resembling it, with which his Majesty was pleased: gave me his hand to kiss and commanded me to wait on him at Marleborough when he went to Bath with the Queen (which was about a fortnight after) which I did: and the next day, when the court were on their journey, his Majesty left the Queen and diverted to Aubury, where I showed him that stupendious Antiquity, with the view whereof, He and his Royal Highness, the Duke of York, were very well pleased. His Majesty commanded me to write a Description of it, and present it to him: and the Duke of York commanded me to give an account of the old Camps, and Barrows on the Plains.

As his Majesty departed from Aubury to overtake the Queen, he cast his eye on Silsbury-hill about a mile off: which they had the curiosity to see, and walked up to the top of it, with the Duke of York, Dr. Charlton and I attending them…

Famed diarist Samuel Pepys also visited Avebury five years later and mentioned the king’s interest in it:

In the afternoon came to Abury, where seeing great stones like those of Stonehenge standing up, I stopped, and took a countryman of that town, and he carried me and showed me a place trenched in like Old Sarum almost, with great stones pitched in it, some bigger than those at Stonehenge in figure, to my great admiration: and he told me that most people of learning coming by do come and view them, and that the King (Charles II.) did so: and the mount cast hard by is called Silbury, from one King Seall buried there, as tradition says… about a mile off, it was prodigious to see how full the downs are of great stones…

Aubrey himself went on to explain his own theory about these ancient sites.

…it is cleer that all the monuments, which I have here recounted were Temples. Now my presumption is… that these ancient monuments [sc. Aubury, Stonehenge, Kerrig y Druidd &c.]4 were Temples of the Priests of the most eminent Order, viz., Druids, and it is strongly to be presumed, that Aubury, Stoneheng, &c., are as ancient as these times.

This inquiry, I must confess, is a groping in the dark: but although I have not brought it into a clear light, yet I can affirm that I have brought it from an utter darkness to a thin mist, and have gone farther in this essay than any one before me.

These antiquities are so exceedingly old that no books do reach them, that there is no way to retrieve them but by comparative antiquity, which I have writ upon the spot from the monuments themselves… and though this be writ, as I rode a gallop, yet the novelty of it, and the faithfulness of the delivery, may make some amends for the uncorrectness of the style.

The first draught was worn out with time and handling, and now, methinks, after many years lying dormant, I come abroad, like the ghost of one of those Druids.

I beg the reader’s pardon for running this preface into a story, and wish him as much pleasure in reading them, as I met in seeing them.

Of course, we know now that Avebury is much older than the (Iron Age) Druids, dating back to the Neolithic era nearly 5,000 years ago.

While there’s no substitute for seeing them (I’ve been to Avebury many times), there’s still pleasure in reading about these and other ancient treasures to this day. and I’m delighted to say I recently took over a 45-year-old magazine all about this sort of stuff. And as a side project to that, I’ve also launched a new monthly Substack newsletter with curated news, events and links relating to archaeology, folklore and more. Do sign up for free here:

And the similarity to John Aubrey’s own surname wasn’t lost on him, as he mentions it in his writings.

Later known as Monumenta Britannica, much studied in manuscript form in Oxford’s Bodleian Library, but only published in an accessible form in the 1980s. I have taken the text from a Victorian collection of Aubrey’s writing about Wiltshire. The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography describes the Monumenta as “the foundation text of modern archaeology”. Aubrey got as far as discussing the work with a publisher, but they couldn’t agree on the format.

Chorography is a now little-used term for a regional topographic study.

Kerrig y Druidd is a lost monument in north Wales.