I was tired of nothing here but their excessive drinking, for in this place you may have the best of company and conversation

One of my favo(u)rite novels of recent years has to be Golden Hill by Francis Spufford, which follows the adventures of the mysterious Mr Smith as he arrives in New York in 1746, clutching a bill for a thousand pounds and unwilling to reveal why. The tale is told in a dashing 18th-century pastiche style, and has some marvellous twists as we follow Smith’s rakish adventures in the fledgling city.

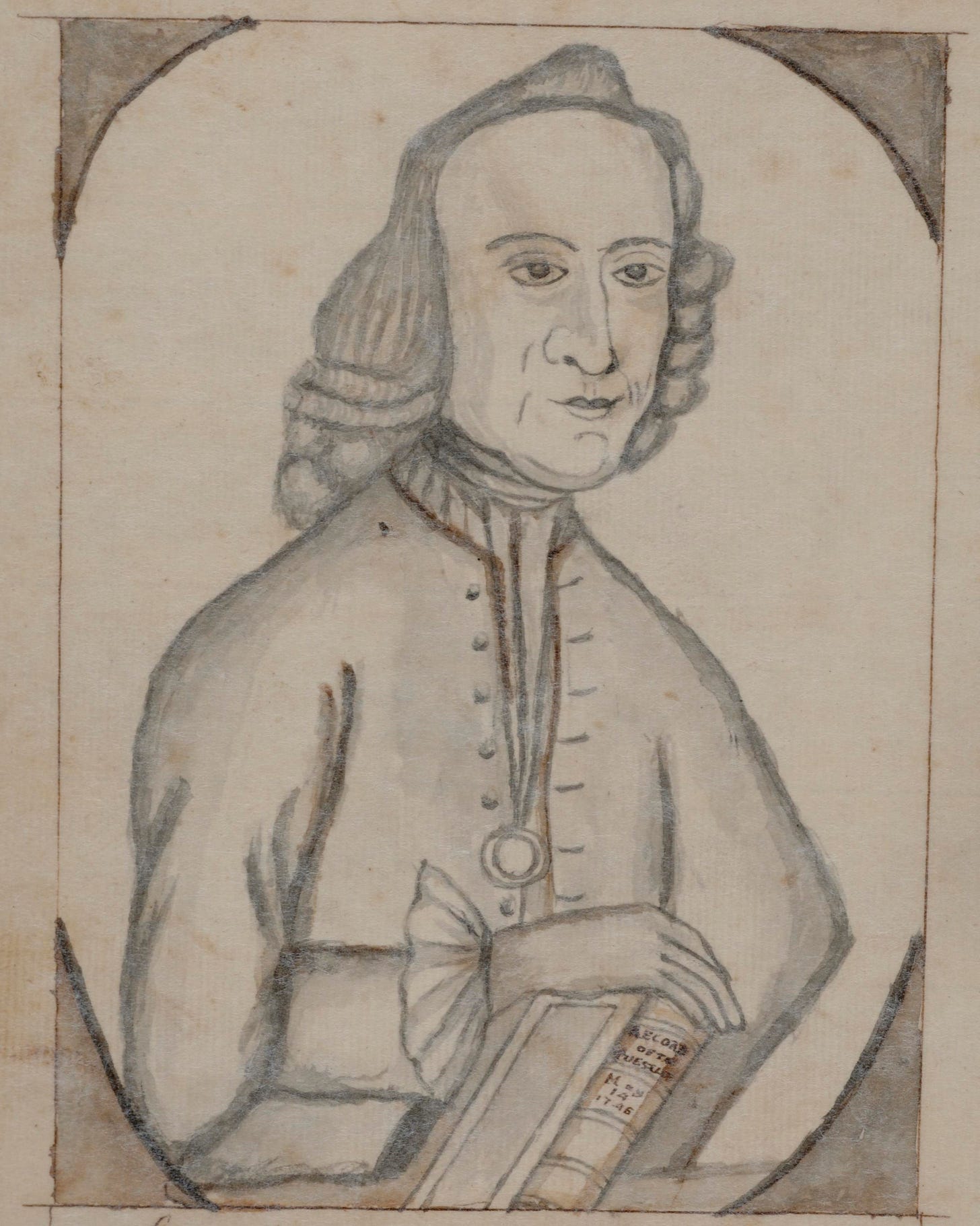

I’ve long meant to dig into the sources Spufford might have used, and it turns out that a key one was a travel diary from 1744, published as Gentleman’s Progress: The Itinerarium of Dr. Alexander Hamilton. Hamilton was born into the Scottish gentry near Edinburgh in 1712 and emigrated to Maryland in 1738, where he set up his practice as a doctor in Annapolis. Hamilton’s Itinerarium follows his travels from Annapolis to York, Maine, via Delaware, Pennsylvania, New York and much of New England. He gives us unique first-hand impressions of these places, not to mention amusing anecdotes as he observes the manners and behaviour of these developing settlements, wedged in the period of British rule between colonisation and independence.

Hamilton passed through New York three times on his trip, and here are some of his encounters and observations. Note that New York (which changed its name in 1664 from New Amsterdam and was still much influenced by Dutch culture) was at this point no larger than a rural market town in Britain today. (Its population was 7,248 in 1723 and rose to 13,046 in 1756 – this had nearly doubled 20 years on from that.)

Friday June 15th

At six o’clock in the evening I landed at New York. This city makes a very fine appearance for above a mile all along the river, and here lies a great deal of shipping. I put my horses up at one Waghorn’s at the sign of the Cart and Horse. There I fell in with a company of toapers. Among the rest was an old Scotsman, by name Jameson, sheriff of the city, and two aldermen, whose names I know not. The Scotsman seemed to be dictator to the company; his talent lay in history, having a particular knack at telling a story. In his narratives he interspersed a particular kind of low wit, well known to vulgar understandings, and having a homely carbuncle kind of a countenance, with a hideous knob of a nose, he screwed it into a hundred different forms while he spoke, and gave such a strong emphasis to his words that he merely spit in one’s face at three or four feet distance, his mouth being plentifully bedewed with salival juice by the force of the liquor which he drank and the fumes of the tobacco which he smoaked. The company seemed to admire him much, but he set me a-staring. After I had sat some time with this polite company, Dr. Colchoun, surgeon to the fort, called in, to whom I delivered letters, and he carried me to the tavern, which is kept by one Todd, an old Scotsman, to sup with the Hungarian Club, of which he is a member, and which meets there every night. The company were all strangers to me, except Mr. Home, Secretary of New Jersey, of whom I had some knowledge, he having been at my house at Annapolis. They saluted me very civilly, and I, as civilly as I could, returned their compliments… Two or three toapers in the company seemed to be of opinion that a man could not have a more sociable quality or enduement than to be able to pour down seas of liquor, and remain unconquered, while others sank under the table. I heard this philosophical maxim, but silently dissented to it. I left the company at ten at night pretty well flushed with my three bumpers [alcoholic drinks – possibly whisky], and ruminating on my folly went to my lodging at Mrs. Hogg’s in Broad Street.

Saturday, June 16th

I breakfasted with my landlady’s sister, Mrs. Boswall. In the morning Dr. Colchoun called to see me, and he and I made an appointment to dine at Todd’s. In the afternoon I took a turn thro’ several of the principal streets in town, guarding against staring about me as much as possible, for fear of being remarked for a stranger, gaping and staring being the true criterion or proof of rustic strangers in all places. The following observations occurred to me:— I found the city less in extent, but by the stir and frequency upon the streets, more populous than Philadelphia. I saw more shipping in the harbour. The houses are more compact and regular, and in general higher built, most of them after the Dutch model, with their gavell ends fronting the street. There are a few built of stone; more of wood, but the greatest number of brick, and a great many covered with pantile and glazed tile with the year of God when built figured out with plates of iron, upon the fronts of several of them. The streets in general are but narrow, and not regularly disposed. The best of them run parallel to the river, for the city is built all along the water, in general. This city has more of an urban appearance than Philadelphia. Their wharfs are mostly built with logs of wood piled upon a stone foundation. In the city are several large public buildings. There is a spacious church, belonging to the English congregation, with a pretty high, but heavy, clumsy steeple, built of freestone, fronting the street called Broadway. There are two Dutch churches, several other meetings, and a pretty large Town-house at the head of Broad street. The Exchange stands near the water, and is a wooden structure going to decay. From it a pier runs into the water called the Long Bridge, about fifty paces long, covered with plank and supported with large wooden posts. The Jews have one synagogue in this city. The women of fashion here appear more in public than in Philadelphia, and dress much gayer. They come abroad generally in the cool of the evening and go to the Promenade. I returned to my lodging at four o’clock, being pretty much tired with my walk. I found with Mrs. Boswall a handsome young Dutchwoman. We drank tea, and had a deal of trifling chat; but the presence of a pretty lady, as I hinted before, makes even trifling agreeable…

Sunday, June 17th

At breakfast I found with Mrs. Boswall some gentlemen, among whom was Mr. J—ys, an officer of the customs in New York. To me he seemed a man of an agreeable conversation and spirit. He had been in Maryland some years ago, and gave me an account of some of his adventures with the planters there. He showed me a deal of civility and complaisance, carried me to church, and provided me with a pew. The minister who preached to us was a stranger. He gave us a good discourse upon the Christian virtues. There was a large congregation of above a thousand, among whom was a number of dressed ladies… There is a pretty organ at the west end of the church, consisting of a great number of pipes handsomely gilt and adorned; but I had not the satisfaction of hearing it play, they having at this time no organist; but the vocal music of the congregation was very good…

At six o’clock I went to see the fort and battery. The castle, or fort, is now in ruins, having been burnt down three or four years ago by the conspirators, but they talk of repairing it again. The Lieutenant-Governour had here a house and a chapel, and there are fine gardens and terrace walks, from which one has a very pretty view of the city. In the fort are several guns, some of them brass and cast in a handsome mould… The main battery is a great half-moon or semicircular rampart bluff upon the water, being turf upon a stone foundation, about 100 paces in length, the platform of which is laid in some places with plank, in others with flagstone. Upon it there are fifty-six great iron guns, well mounted, most of them being thirty-two pounders. Mr. J—ys told me that to walk out after dusk upon this platform was a good way for a stranger to fit himself with a courtesan; for that place was the general rendezvous of the fair sex of that profession after sunset. He told me there was a good choice of pretty lasses among them, both Dutch and English. However, I was not so abandoned as to go among them, but went and supped with the Club at Todd’s. It appeared that our landlord was drunk, both by his words and actions. When we called for anything he hastily pulled the bell-rope, and when the servants came up, Todd had by that time forgot what was called for… I went home after twelve o’clock.

Tuesday, June 19th

… We dined at Todd’s, with seven in company, upon veal, beefsteaks, green pease, and raspberries for a dessert… At night I went to a tavern fronting the Albany coffee-house along with Doctor Colchoun, where I heard a tolerable concerto of musick, performed by one violin and two German flutes. The violin was by far the best I had heard played since I came to America.

Wednesday, June 20th

I dined this day at Todd’s, where I met with one Mr. M—ls, a minister at Shrewsbury in the Jerseys, who had formerly been for some years minister at Albany. I made an agreement to go to Albany with him the first opportunity that offered. I inquired accordingly at the coffee-house for the Albany sloops, but I found none ready to go. I got acquainted with one Mr. Weemse, a merchant of Jamaica, my countryman and fellow lodger at Mrs. Hogg’s. He had come here for his health, being afflicted with the rheumatism. He had much of the gentleman in him, was good-natured, but fickle; for he determined to go to Albany and Boston in company with me; but, sleeping upon it, changed his mind. He drank too hard, whence I imagined his rheumatism proceeded more than from the in temperature of the Jamaica air.

After dinner I played backgammon with Mr. Jeffreys, in which he beat me two games for one.

[Next Hamilton visits Nutting Island, now Governors Island.]

Thursday, June 21st

… Having a contrary wind and an ebb tide, we dropped anchor about half a mile below New York, and went ashore upon Nutting Island, which is about half a mile in dimension every way, containing about sixty or seventy square acres. We there took in a cask of spring water. One half of this island was made into hay, and upon the other half stood a crop of good barley, much damaged by a worm which they have here, which so soon as their barley begins to ripen cuts off the heads of it… It is called Nutting Island from its bearing nuts in plenty, but what kind of nuts they are I know not, for I saw none there. I saw myrtle berries growing plentifully upon it, a good deal of juniper and some few plants of the ipecacuan. The banks of the island are stony and steep in some places. It is a good place to erect a battery upon, to prevent an enemy’s approach to the town, but there is no such thing, and I believe that an enemy might land on the back of this island out of reach of the town battery and plant cannon against the city or even throw bombs from behind the island upon it.

We had on board this night six passengers, among whom were three women. They all could talk Dutch but myself and Dromo [the slave who accompanied Hamilton], and all but Mr. M—s seemed to prefer it to English. At eight o’clock at night, the tide serving us, we weighed anchor, and turned it up to near the mouth of North River, and dropt anchor again at ten, just opposite to the great church in New York.

Friday, June 22nd

While we waited the tide in the morning, Mr. M—s and I went ashore to the house of one Mr. Van Dames, where we breakfasted, and went from thence to see the new Dutch church, a pretty large but heavy stone building, as most of the Dutch edifices are, quite destitute of taste or elegance. The pulpit of this church is prettily wrought, being of black walnut. There is a brass supporter for the great Bible that turns upon a swivel, and the pews are in a very regular order. The church within is kept very clean, and when one speaks or hollows there is a fine echo. We went up into the steeple, where there is one pretty large and handsome bell, cast at Amsterdam, and a publick clock. From this steeple we could have a full view of the city of New York.

Monday, July 9th

The people of New York, at the first appearance of a stranger, are seemingly civil and courteous, but this civility and complaisance soon relaxes if he be not either highly recommended or a good toaper. To drink stoutly with the Hungarian Club, who are all bumper men, is the readiest way for a stranger to recommend himself, and a set among them are very fond of making a stranger drunk. To talk bawdy and to have a knack at punning passes among some there for good sterling wit. Governour Clinton himself is a jolly toaper and gives good example, and for that one quality is esteemed among these dons…

[New York’s gentry in this era were alas supported in their comforts by many black slaves. In Hamilton’s account he refers to reading a ‘Journal of Proceedings’, which was an account of the ‘New York Conspiracy’ in 1741 alluded to in the next section – this was an alleged plot between black slaves and poor white people to overthrow the governor, and after various fires in the city, more than 100 of these supposed plotters were executed or exiled. Historians do not regard the court cases at the time as reliable.]

The staple of New York is bread flour and skins. It is a very rich place, but it is not so cheap living here as at Philadelphia. They have very bad water in the city, most of it being hard and brackish. Ever since the negro conspiracy, certain people have been appointed to sell water in the streets, which they carry on a sledge in great casks and bring it from the best springs about the city, for it was when the negroes went for tea water that they held their cabals and consultations, and therefore they have a law now that no negro shall be seen upon the streets without a lanthorn after dark.

In this city are a mayor, recorder, aldermen, and common council. The government is under the English law, but the chief places are possessed by Dutchmen, they composing the best part of the House of Assembly. The Dutch were the first settlers of this Province, which is very large and extensive, the States of Holland having purchased the country of one Hudson, who pretended first to have discovered it, but they at last exchanged it with the English for Saranam, and ever since there have been a great number of Dutch here, tho’ now their language and customs begin pretty much to wear out, and would very soon die were it not for a parcel of Dutch domines here, who, in the education of their children, endeavour to preserve the Dutch customs as much as possible. There is as much jarring here betwixt the powers of the Legislature as in any of the other American Provinces.

They have a diversion here very common, which is the barbecuing of a turtle, to which sport the chief gentry in town commonly go once or twice a week.

There are a great many handsome women in this city. They appear much more in public than at Philadelphia. It is customary here to ride thro’ the street in light chairs. When the ladies walk the streets in the daytime they commonly use umbrellas, prettily adorned with feathers and painted.

There are two coffee-houses in this city, and the northern and southern posts go and come here once a week. I was tired of nothing here but their excessive drinking, for in this place you may have the best of company and conversation as well as at Philadelphia.

Friday, August 31st

I arrived in New York about eleven o’clock, and put up my horses at Waghorn’s. After calling at Mrs. Hogg’s, I went to see my old friend Todd, expecting there to dine, but accidentally I encountered Stephen Bayard, who carried me to dine at his brother’s. There was there a great company of gentlemen… There were thirteen gentlemen at table, but not so much as one lady. We had an elegant, sumptuous dinner, with a fine dessert of sweetmeats and fruits, among which last there were some of the best white grapes I have seen in America.

… One there who set up for a dictator talked very much to the discredit of Old England, preferring New York to it in every respect whatsoever relating to good living. Most of his propositions were gratis dicta , and it seemed as if he either would not or did not know much of that fine country England. He said that the grapes there were good for nothing but to set a man’s teeth on edge; but to my knowledge I have seen grapes in gentlemen’s gardens there far preferable to any ever I saw in these northern parts of America. He asserted also that no good apple could be brought up there without a glass and artificial heat, which assertion was palpably false and glaringly ignorant, for almost every fool knows that apples grow best in northern climates betwixt the latitudes of thirty-five and fifty, and that in the southern hot climes, within the tropics, they don’t grow at all, and therefore the best apples in the world grow in England and in the north of France. He went even so far as to say that the beef in New York was preferable to that of England. When he came there I gave him up as a trifler, and giving no more attention to his discourse, he lost himself, the Lord knows how or where, in a thicket of erroneous and ignorant dogmas, which any the most exaggerating traveller would have been ashamed of. But he was a great person in the place, and therefore none in the company was imprudent enough to contradict him, tho’ some were there that knew better.

Next time… a frosty reception!

I think these extracts confirm my Australian experience that, in a cultural desert, alcohol tends to fill the void and, the violin concert notwithstanding, New York seems not to have been a centre of culture at the time of Mr Hamilton's visit.