My precious burden, 1800

Clogs on, or clogs off? It depends.

It’s probably not often that one could argue a teenager taking a walk in the countryside ultimately affected the lives of millions across the world.

Let’s back up a little and set the scene. Last week I was on holiday in rural north Wales. One day we went to the ruins of Castell y Bere, perched on a rocky outcrop in the beautiful Dysynni valley and in the foothills of Cadair Idris. Just up the valley lies the little village of Llanfihangel-y-Pennant, where the church of St Michael and a ruined cottage commemorate the story of Mary Jones.

That ruined cottage was Tyn-y-ddôl, once home to weavers Jacob and Mary Jones, also known as James and Molly, devout members of the local Calvinistic Methodist church a couple of miles away. Their daughter Mary, also known as Mari Jacob, was born there on 16 December 1784 and grew up helping in the household – her father died when she was only four. Thanks to a local ‘circulating school’ and associated Sunday school – set up as part of the regional remit of one Rev Thomas Charles – Mary learned to read (in Welsh, of course) and became particularly devoted to the Bible. But these people were poor and could not afford a copy of their own, especially as Welsh Bibles were in short supply – so Mary would typically walk across the fields to read a copy owned by a local farmer. And she saved her earnings from doing chores for neighbours so she could eventually buy her own.

There are various versions of her subsequent adventure, some embellished by enthusiastic Victorian Christians, but it transpires that her own words have survived to confirm the core of it (and of course we’ll come to those): one day in 1800, when she was only 15 years old, she set out across the hills, barefoot as was her custom but carrying clogs so she could be respectable on arrival, and walked 26-or-so demanding miles to the market town of Bala in order to buy a Bible from Thomas Charles himself, who was based there. In 1799 the Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge had printed 10,000 Welsh Bibles, and over time he secured 700 of them for local distribution. When the footsore Mary arrived, he had no stock in, but he allowed her to stay until the next delivery arrived. The story of this devout solitary pilgrimage went down in legend – thanks to Charles himself, and he used it to promote the cause of printing and disseminating Bibles wherever they were needed. This began with Wales, of course, through the work of the Religious Tract Society, but in March 1804 Charles joined a group of like-minded souls, including the legendary campaigner against slavery William Wilberforce, and founded the British and Foreign Bible Society (still going today as the Bible Society), an inter-denominational group with the specific purpose of making the Bible available worldwide.

The BFBS was never a missionary society, but of course the countless Victorian missionaries who travelled across the world to spread the word of God needed Bibles, and the BFBS provided translations in a multitude of languages – the first being Mohawk. This work is not without controversy – it has been accused of cultural imperialism and creating dependence on foreign support, and of helping to eradicate native cultures across the world. On the plus side it has been part of an improvement in the lives of many people too. We shouldn’t blame Mary Jones for any of this, of course – these wheels were turning anyway, but certainly the story of her dogged devotion provided a focus for pioneers like Charles and helped the global cause of Christianity.

Charles himself continued to work tirelessly, particularly in service to Welsh Methodism and local education, and died exhausted at the age of 59 in 1814. As for Mary, she continued to live an ordinary life, marrying weaver Thomas Lewis and raising a family (as well as being a successful beekeeper) in Bryncrug, further down the Dysynni valley near Tywyn, as devout as ever and supporting local Christian endeavours. Only one of their six children survived to adulthood, and emigrated to America. Mary died in December 1866 at the age of 80 and is buried at Bryncrug. Two of the Bibles she bought that day in 1800 are still held in libraries, in Cambridge (inscribed by Mary herself) and Aberystwyth.

The first known written account of her story dates from a BFBS journal in 1867. It was then more widely told in 1878,1 but in fact Mary had told her own story more than a decade earlier. In 1862, a young woman called Lizzie Rowlands moved from Bala to work as a governess near Bryncrug and befriended the elderly Mary. Lizzie described her thus:

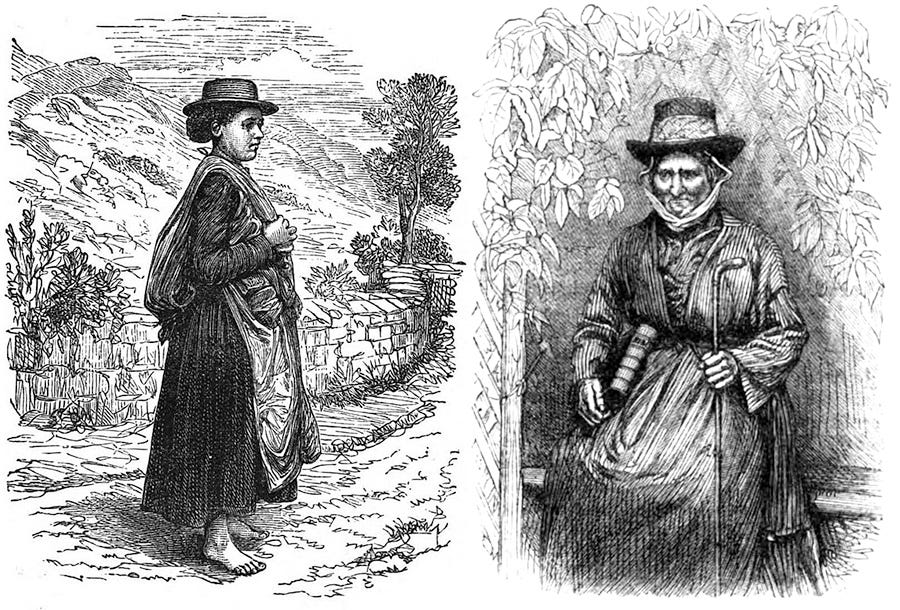

She was nearly 80 years old, small, thin and quite blind these many years, living in a small, miserable cottage. The poorest I have ever been in with an earthen floor, a small table with a rush candle on it and 2 or 3 three-legged stools. She wore the old Welsh dress, a petticoat and bed gown, an apron made of linsey and a white cap. To go out to chapel, she would wear a ‘Jim Crow’ [a soft felt hat], a blue homespun cloak and a hood and carry her stick in her hand. In winter she used to carry a lantern with horn windows, not to light her way, she could not see, but so as others could see her.2

It was Lizzie who upbraided a man called Robert Oliver Rees, who published a somewhat fictionalised version of Mary’s story in Welsh in 1879 (an English book based on it was published by the BFBS in 1882) – she said his version was “too sentimental” and riddled with “falsehoods”. And it’s thanks to Lizzie that we have a few words she transcribed from Mary herself about her youthful adventure, which I give you below (bearing in mind they were recalled more than 60 years after the event).3

One stormy Monday morning I was walking to a farmhouse about 2 miles from my home. A gentleman riding a white horse and wearing a cloth cape came to meet me and asked where I was going through such wind and rain. I said I was going to a farmhouse where there was a Bible, that there wasn’t one nearer my home and that the mistress of the farm had said that I could see the Bible which she kept on a table in the parlour, as long as I took my clogs off. I told him that I was saving every halfpenny, this long time, to get a Bible but that I didn’t know where I could get one. The gentleman was Charles of Bala. He told me to come at a certain time, that he was expecting some Bibles from London and that I could have one from him.

When the time came, my mother put the money and a little bread and cheese in one end of a wallet and my clogs in the other, and I set off for Bala on a fine morning, resting where there was a stream of clear water, to eat the bread and cheese. I came to Bala, and trembling, knocked on the door of Mr Charles’ house. I asked for Mr Charles and was told he was in his study at the back of the house. I was allowed to go to him and he told me the Bibles had not arrived. I started to cry because I did not know where to stay. He sent me to an old servant of his who had a house at the bottom of the garden, until the Bibles came. When they came, Mr Charles gave me three for the money, that is the price of one. I set off home with my precious burden. I ran a great part of the way, I was so glad of my Bible.

Lizzie Rowlands’ original papers are held at the National Library of Wales.

I first found them at the lovely little exhibition in St Michael’s in Llanfihangel-y-Pennant. In Bala you can also find the Mary Jones World visitor centre, set up by the Bible Society in 2014; it is in the church of the graveyard where Charles is buried.