My ever dear General, 1806

Behind every great revolutionary…

One happy consequence of working as a history editor is that something fascinating and perhaps little known often comes my way. This week’s Histories is the fruit of exactly such a situation, and I am indebted to Dr Charmian Kenner for making this possible (more on her work shortly!).

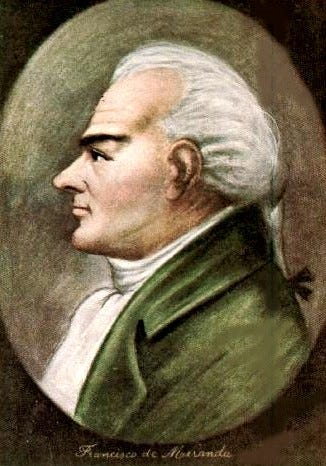

Let’s set the scene. Enter Francisco de Miranda (1750–1816, full name the impressive Sebastián Francisco de Miranda y Rodríguez de Espinoza), a man born for revolution. He grew up in a wealthy family in Caracas, Venezuela, which at the time as part of the Spanish Viceroyalty of New Granada. After a good education at home, Miranda continued it in Spain, beginning to amass a vast library while also training as a military officer. He fought for Spain in Morocco in the 1770s, although here the first seeds of doubt about the whole colonial enterprise were planted.

In the 1780s, Miranda went on to fight in the American War of Independence, with Spain supporting America against the British; Miranda became friends with leaders such as George Washington, but he also began to make enemies among the Spanish authorities. There is barely a country in Europe he didn’t visit in this decade, and there are even rumours of a fling with Catherine the Great in Russia. He also fought in the French Revolution in the 1790s, but again made enemies as he started to question the new republic’s Reign of Terror. He left for England in early 1798, setting up his base in London, and from 1804 onwards he began in earnest to focus on liberating his homeland Venezuela from Spanish rule, partly with British help. He declared its first republic in 1811 and although had mixed success, he set the stage for Simón Bolivar’s lasting success with independence.

This breathless summary of Miranda’s astonishing life only touches the surface, because he isn’t even our real focus this week. That honour goes to a Yorkshire shoemaker’s daughter by the name of Sarah Andrews (1774–1847). She is barely mentioned, if at all, in Miranda’s entries in dictionaries of biography and encyclopedias, and it’s thanks to Dr Kenner that her story has finally been properly told.

We don’t know exactly when Sarah Andrews met Francisco de Miranda. She came from Market Weighton, halfway between York and Hull, and probably through her mother Dinah’s brother, a portrait painter, she moved to London with some of her siblings just before the turn of the century. And we know from a letter by Miranda in February 1800 that she was in his house, referred to as Sally, and possibly working as his housekeeper; she was 25 and he was 49. There is no proof of whether they married or not, but they had two sons together, Leandro in 1803 and Francisco in 1806.

It was also to be “my very dear Sally” who kept their long-term London home at 27 Grafton Street (now 58 Grafton Way, marked with a plaque to Miranda) from 1802, with Miranda often away (particularly from 1805 to 1807) or even imprisoned (in 1814). She provided a hub for intelligence and his network of supporters, as well as nurturing their children and guarding his 6,000-volume library (the largest private collection in London at the time) while also wrestling with poverty and debt. The last known communication between them is a letter from prison in Cádiz in May 1814, and he died there in July 1816. She would maintain their Grafton Street home as a base for international revolutionaries for many years, until her death in 1847.

The fascinating story of Sarah and Francisco, set in the wider context of Latin American independence, is told in Charmian Kenner’s free ebook Revolutionary Partners, and I urge you to read it! With thanks to Dr Kenner, below I give you just one of Sarah’s letters, typically addressed to “My ever dear General” or “My ever dearest G”; they used the aliases Mr and Mrs Martin as protection from Spanish government spies. Sarah’s very personal letter gives a flavour of her stalwart support while trying to run a home and family.1

My ever dear General,

It was with the greatest pleasure I heard of your good health through Mr Vansittart [then the British Secretary to the Treasury, and later Chancellor of the Exchequer]. A few lines from your dear hands would have been very pleasing; we are all anxiety for your news and we are now counting the days with impatience.

I hope and trust a few weeks more will decide this grand work. Our reports are so various and contradictory that it is impossible to put any reliance on any of them. I copy all the papers I can get; the articles in some of them are very curious. I have made a book of them, which I will send you, by and by—it is the wish here that you succeed, the generality of the people are confident of it. I hope and pray hourly for it for the sake of us all…

My lovely children improve every day. My Leander2 is more beautiful than ever, he grows very stout and tall, he is very sensible and [has] an uncommon memory. When I tell him of his papa he remembers it a week after, and tells me every word. He often asks me to talk of papa, about pretty things and what you will buy him when he comes to America. He knows all his letters. We often stop in the street to read; every paper he sees he brings to me to read news about the General: “Is it good news, Mama? O very well, then Leander will go to his ship, and to Caracas to Papa.”

He has the best temper in the world; he is only in passion for a moment and then only tell him that you would be angry with him, he is good in a moment. He has such a noble look and his countenance and manner is so grand that I never walk out with him, but I am asked whose child he his. I am very proud of my darling boy, he is my companion in all my walks.

Capton Grose is a constant visitor, always speaking of you. [This is presumably Francis Grose, 1758–1814, who had been Lieutenant Governor of New South Wales.] The Abbé [the French exile and book dealer Abbé Dulonchamp] is still here but as impatient as ever to visit his country. He is often speaking about his printing press – he wants me to buy it for you. I tell him that is impossible… All your friends have been unremitting in their enquiries after your prosperity.

Mr Turnbull [Miranda’s friend John Turnbull, a merchant] is led very much by reports: when good I see them; on the contrary, they never come near me. They are very mean: I was very short of money, I asked him a few pounds, he told me he had no money of yours in his hands, and I had better wait until I heard some news from you…

God bless your my ever dear and affectionate friend, and may God direct and prosper all your undertaking is the sincere prayer of your faithful and obedient friend,

Sarah Martin.

P.S. … Leander sends his love, and a kiss—he is 3 years old 9th of this month, 13 months since you saw my dear child this day.

I have taken the liberty of modernising Sarah’s spelling and grammar for ease of reading, based on Dr Kenner’s transcription of the original. I have cut a few sections about some of their friends and servants.

Miranda sailed to Venezuela in February 1806 in a ship he named Leander in his son’s honour. Leander himself went to live in Venezuela and ran a bank there, though his own son was born in London and there are descendants alive today.