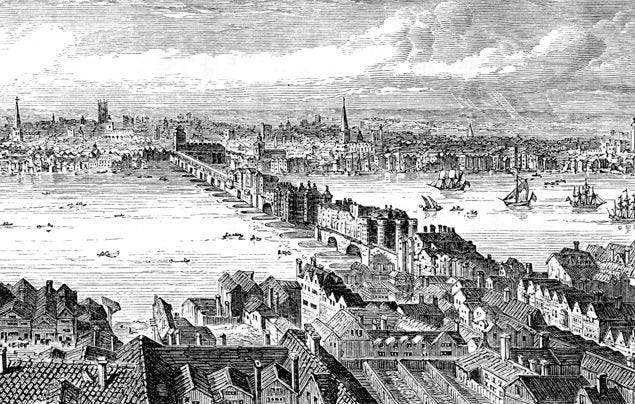

Life in the Smoke, 1661

Anyone for pea soup?

… The weary Traveller, at many Miles distance, sooner smells, than sees the City to which he repairs. This is that pernicious Smoke which sullies all her Glory…

Air pollution is often in the news – only this week the British Medical Journal published an article entitled ‘Air pollution is a public health emergency’, which refers to the Great Smog of 1952 that directly led to thousands of deaths – and it’s certainly not a new subject to the smog-ridden folk of London. It was discussed as early as the 13th century, and there was a notable pamphlet written about it in the 17th century by one of our great diarists.

Fumifugium, or, The inconveniencie of the aer and smoak of London dissipated together with some remedies humbly proposed by J.E. esq. to His Sacred Majestie, and to the Parliament now assembled was written in 1661 by the diarist John Evelyn, whom we previously met through his writings about the frost fairs. As a keen gardener, he was a careful observer of the weather; he was also a founder of the Royal Society (in 1660) who had studied anatomy, and became a government commissioner for improving the streets of London. His Fumifugium was addressed to King Charles II in the form of a three-part letter, and is regarded as a pioneering work in the field of air pollution analysis.

Fumifugium clearly attracted attention, too. Not long after (probably at the beginning of 1663), a ‘broadside’ (a populist form of poetry, often referring to issues of the day) was written which referenced it: the ‘Ballad of Gresham Colledge’. This was only published in printed form in 1932 in the journal Isis by Dorothy Stimson, who argues convincingly in her introductory essay that its author was Joseph Glanvill (1636–1680).1 He was a writer and clergyman who was also friends with the founders of the Royal Society, which the ballad celebrates. Gresham College exists to this day, offering wonderful free public lectures, and was the original meeting place of the Society. The ballad directly refers to Evelyn’s work and how he “writes soe learnedly of smoake”:

He shewes that ’tis the seacoale smoake That allways London doth Inviron, Which doth our Lungs and Spiritts choake, Our hanging spoyle, and rust our Iron. Lett none att Fumifuge be scoffing Who heard att Church our Sundaye’s Coughing.

Of course, all this was written only a few years before London’s smoke problem became far worse for a short time, in the form of the Great Fire, which we have watched before. Below are some extracts of Evelyn’s work (I have modernised some of the spelling).2

[Here’s how Evelyn introduces his subject…]

Sir, It was one day, as I was Walking in Your MAJESTY’S Palace, at WHITE-HALL… that a presumptuous Smoke issuing from one or two Tunnels near Northumberland House, and not far from Scotland Yard, did so invade the Court; that all the Rooms, Galleries, and Places about it were fill’d and infested with it; and that to such a degree, as Men could hardly discern one another for the Cloud, and none could support, without manifest Inconveniency… Your Majesty who is a Lover of noble Buildings, Gardens, Pictures, and all Royal Magnificences, must needs desire to be freed from this prodigious annoyance… the Evil is so Epidemical; endangering as well the Health of Your Subjects…

[In the first main section, he describes the current misery and its causes, chief among them the smoke from burning ‘sea-coal’ (this term originally referred to coal found on seashores and beneath cliffs, but later came to mean coal transported to London by sea).]

… what we do here so much declaim against, since this is certain, that of all the common and familiar materials which emit it, the immoderate use of, and indulgence to Sea-coal alone in the City of London, exposes it to one of the foulest Inconveniences and reproaches, that can possibly befall so noble, and otherwise, incomparable City: And that, not from the Culinary fires, which for being weak, and less often fed below, is with such ease dispell’d and scatter’d above, as it is hardly at all discernible, but from some peculiar Tunnels and Issues, belonging only to Brewers, Dyers, Lime-burners, Salt, and Soap-boilers, and some other private Trades, One of whose Spiracles alone, does manifestly infect the Air, more, then all the Chimneys of London put together besides… For when in all other places the Air is most Serene and Pure, it is here Eclipsed with such a Cloud of Sulphur, as the Sun itself, which gives day to all the World besides, is hardly able to penetrate and impart it here; and the weary Traveller, at many Miles distance, sooner smells, than sees the City to which he repairs. This is that pernicious Smoake which sullies all her Glory, superinducing a sooty Crust or fur upon all that it lights… and executing more in one year, than expos’d to the pure Air of the Country it could effect in some hundreds.

It is this horrid Smoke which obscures our Churches, and makes our Palaces look old, which fouls our Clothes, and corrupts the waters, so as the very Rain, and refreshing Dews which fall in the several Seasons, precipitate this impure vapour, which, with its black and tenacious quality, spots and contaminates whatsoever is expos’d to it:

It is this which scatters and strews about those black and smutty Atoms upon all things where it comes, insinuating it self into our very secret Cabinets, and most precious Repositories… [it] kills our Bees and Flowers abroad, suffering nothing in our Gardens to bud, display themselves, or ripen…

… it is manifest, that those who repair to London, no sooner enter into it, but they find a universal alteration in their Bodies, which are either dried up or enflam’d, the humours being exasperated and made apt to putrify, their sensories and perspirations so exceedingly stopp’d, with the losse of Appetite, and a kind of general stupefaction, succeeded with such Cattarhs and Distillations, as do never, or very rarely quit them, without some further Symptoms of dangerous Inconveniency so long as they abide in the place; which yet are immediately restored to their former habit, so soon as they are retired to their Homes and enjoy the fresh Air again…

The Consequences then of all this is, that (as was said) almost one half of them who perish in London, die of Phthisical and Pulmonic distempers; That the Inhabitants are never free from Coughs and importunate Rheumatisms, spitting of Impostumated and corrupt matter: for remedy whereof, there is none so infallible, as that, in time, the Patient change his Air, and remove into the Country…

[In Part II, he proposes primarily that the industries which generate the smoke should be removed a few miles outside the city…]

But the Remedy which I would propose, has nothing in it of this difficulty, requiring only the Removal of such Trades, as are manifest Nuisances to the City, which, I would have placed at farther distances; especially, such as in their Works and Furnaces use great quantities of Sea-Coal, the sole and only cause of those prodigious Clouds of Smoke, which so universally and so fatally infest the Air, and would in no City of Europe be permitted, where Men had either respect to Health or Ornament. Such we named to be Brewers, Dyers, Soap and Salt-boilers, Lime-burners, and the like…

I propose therefore, that by an Act of this present Parliament, this infernal Nuisance be reformed; enjoining, that all those Works be removed five or six miles distant from London below the River of Thames… At least by this means Thousands of able Watermen may be employed in bringing Commodities into the City, to certain Magazines & Wharfs, commodiously situated to dispense them by Cars or rather Sleds, into the several parts of the Town; all which may be effected with much facility, and small expense; but, with such Conveniency and Benefit to the Inhabitants otherwise, as were altogether inestimable…

We might add to these, Chandlers and Butchers, because of those horrid stinks, niderous and unwholesome smells which proceed from the Tallow, and corrupted Blood: At least should no Cattel be kill’d within the City (to this day observ’d in the Spanish great Towns of America) since the Flesh and Candles might so easily be brought to the Shambles and Shops from other places less remote then the former; by which means also, might be avoided the driving of Cattle through the Streets, which is a very great inconvenience and some danger: The same might be affirm’d of Fishmongers…

[And in the final section this keen gardener advocates planting all manner of sweet-smelling trees and plants (his lists of these are lengthy!)]

There is yet another expedient, which I have here to offer (were This of the poisonous and filthy Smoke remov’d) by which the City and environs about it, might be rendred one of the most pleasant and agreeable places in the world. In order to this I propose:

That all low-grounds circumjacent to the City, especially East and South-west, be cast and contriv’d into square plots, or Fields of twenty, thirty and forty Acres, or more, separated from each other by Fences of double Palisades, or Contrespaliers, which should enclose a Plantation of an hundred and fifty, or more, feet deep, about each Field… That these Palisad’s be elegantly planted, diligently kept and supplied, with such Shrubs, as yield the most fragrant and odoriferous Flowers, and are aptest to to tinge the Air upon every gentle emission at a great distance:

… by which means the Air and Winds perpetually fann’d from so many circling and encompassing Hedges, fragrant Shrubs, Trees, and Flowers (the amputation and prunings of whose superfluities, may in Winter, on some occasions of weather, and winds, be burnt, to visit the City with a more benign smoke) not only all that did approach the Region, which is properly design’d to be Flowery; but even the whole City, would be sensible of the sweet and ravishing varieties of the perfumes, as well as of the most delightful and pleasant objects, and places of Recreation for the Inhabitants…

As Glanville’s ballad says, “Wee shall instead of coale burne wood” – although of course today we are as concerned about particulates from burning wood as much as from coal. But Evelyn’s suggested measures make clear sense for their time, and the planting of trees and shrubs of course is an ever more important mitigation against climate change in our own times.

Various editions of Fumifugium are available at the Internet Archive.