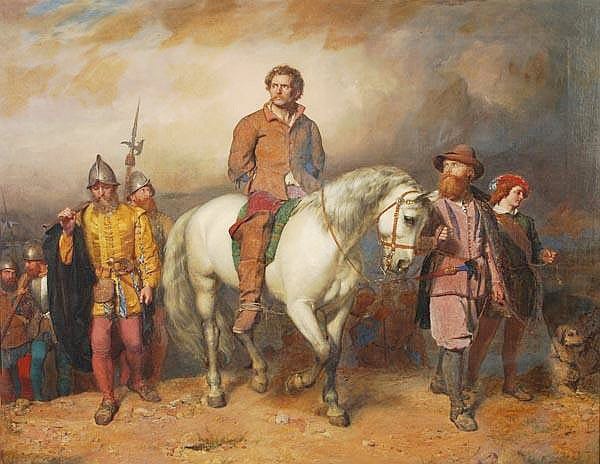

Jailbreak! 1596

Kinmont Willie gets away

O have ye na heard o’ the fause Sakelde?

O have ye na heard o’ the keen Lord Scroop?

You have to feel sorry for Thomas Scrope. He was not yet 30, and his job – as Warden of the English West March, a role which his father Henry had also held – was to police the notoriously violent borders between England and Scotland. When he took up the post in August 1593, he wrote to the Privy Council:

The frontier here is very broken at present… and will be worse as the nights grow long.

These were known as the Debatable Lands – a lawless zone north of Carlisle not quite belonging to either nation, controlled by notorious families of border reivers (raiders) such as the Armstrongs and the roguish Grahams.1 Sometimes they would leave this zone and raid surrounding farms, and local communities lived in fear. To this day you can see ruined fortified ‘bastles’ further east in Northumberland, homes with great thick stone walls where families lived above their livestock and could pull up a ladder if the raiders approached.

One day in March 1596, Scrope’s deputy, Thomas Salkeld, made a dangerous mistake. It had been a ‘day of truce’, one of various occasions when the Scots and the English at least claimed to abandon hostilities to allow local ‘march law’ to be administered. On his way back to Carlisle after the meetings, though, Salkeld, who had 200 men with him, spotted the reiver clan leader William Armstrong – a legendary ruffian and murderer known as Kinmont Willie – on the opposite bank of the Liddel Water river, and gave into the temptation of claiming a notable prize. He and his men gave chase, captured Willie, and locked him up in Carlisle Castle. Did he really think there would be no consequences?

Just under a month later, the consequences turned up. Scrope’s counterpart warden for the Scots was Walter Scott, Baron of Buccleuch (1565–1611), and as an ally of the Armstrongs, he was not happy that Willie was still locked up thanks to Scrope’s uncertainty about how to proceed. We have Thomas Scrope’s own words from 14th April 1596 to explain what happened next…2

April 14th, 1596. Yesternight, in the dead time thereof, Walter Scott of Harding, the chief man about Buccleugh, accompanied with 5003 horsemen of Buccleugh’s and Kinmont’s friends, did come, armed and appointed with gavelocks [a type of crowbar], and crows of iron, handpicks, axes, and scaling ladders, unto an outward corner of the base court of this castle, and to the postern door of the same, which they undermined speedily and quietly, and made themselves possessors of the base court, broke into the chamber where Will of Kinmont was, carried him away, and, in their discovery by the watch, left for dead two of the watchmen, hurt a servant of mine (one of Kinmont’s keepers) and were issued again out of the postern before they were descried by the watch of the inner ward, and before resistance could be made.

The watch, as it should seem, by reason of the stormy night, were either on sleep, or under some covert to defend themselves from the violence of the weather, by means whereof the Scots achieved their enterprise with less difficulty. The warding place of Kinmont, in respect of the manner of his taking, and the assurance he had given that he would not break away, I supposed to have been of sufficient surety, and did not expect that any would have dared to attempt to breach in time of peace any of her Majesty’s castles, a place of such great strength. If Buccleugh himself has been the captain of this proud attempt, since some of my servants tell me they heard his name called out (the truth whereof I shall shortly find out), then I humbly beseech, that her Majesty will be pleased to send to the King, to call for and find that the nature of his offence shall merit retaliation, for it will be a dangerous example to leave this outrageous attempt unpunished… In revenge for which, I intend that something shall shortly be brought against the principals of this action for reparation.

This was a failure for Scrope, and the events which it described made Queen Elizabeth I furious. On 24th June, she wrote to King James VI of Scotland about Buccleuch:

Shall any castle… of mine be assailed by a night largin [thief], and shall not my confederate send the offender to his due punisher?

In fact, the two countries came close to war over this, but Buccleuch turned himself in a year later. He was held in the border town of Berwick-upon-Tweed before being sent to London to face the queen in person. The scene that took place is almost like something from Blackadder, as he wows the Queen:4

…on being presented to her she demanded “how he dared to undertake an enterprise so desperate and presumptuous.”

“What is it,” he replied, “that a man dares not do?”

Elizabeth, turning to a Lord-in-Waiting, said, “With ten thousand such men our brother in Scotland might shake the firmest throne of Europe.”

So Scott got away with it, and was even later elevated as a peer. Kinmont Willie, meanwhile, continued his raids, though his last recorded one was in 1602 – legend has it he died of old age between 1608 and 1611, but his sons continued the family ‘trade’. A well-known border ballad, ‘Kinmont Willie’, still popular today, recounts the jailbreak story in lavish detail:5

All sore astonished stood Lord Scroope,

He stood as still as rock of stane;

He scarcely dared to trew his eyes,

When thro’ the water they had gane.

And what of poor old Thomas Scrope? (Or not so poor – he was a wealthy man, who liked to grumble about his duties.) He took severe reprisals, razing every settlement along a four-mile stretch of the Liddel to the ground and allegedly binding prisoners “two and two together, on a leash like dogs”. But when Elizabeth died in 1603 and James took over the united thrones of Scotland and England, Scrope was sidelined, eventually retiring to Yorkshire and then Nottinghamshire, where he died in 1609. But that union of nations also put an end to the worst days of the reivers.

The full story of this region is well told in Graham Robb’s 2018 book The Debatable Land. There’s much more about this era at the Reivers website. And I can call the Grahams roguish because one of their descendants reads this newsletter!

Scrope’s reports are recorded in the calendar of Scottish state papers, published in 1894 as The Border Papers, edited by Joseph Bain. The text has been lightly modernised.

Probably an exaggeration – other accounts list 40, 80 or 200!

This story was recounted in The Scotts of Buccleuch by William Fraser in 1878, attributed to a “family tradition”.

The ballad was first published by the novelist Walter Scott (a distant relative) in 1802 and is believed by some to have been written by him, albeit based on a source from 1688.

By the way, this morning I attended ScottishIndexes Conferences, where Andrew Armstrong provided a marvellous talk on the Border Reivers including Kinmont. Great details.

Thanks for an interesting bit of history.