I've struck gold! (Part 1, 1851)

But who found it first? And who was like a bloated frog?

(Hello, this is Histories, a free weekly email exploring first-hand accounts from the corners of worldwide history… Do please share this with fellow history fans and subscribe! And a warm welcome to many new subscribers via Storythings and Facebook!)

I regret exceedingly to hear many poor people have left their employment for the purpose of seeking their fortune in the precarious occupation of gold digging… a very great amount of human misery must be the result of this reckless digging mania…

The official history of the gold rush in Australia runs thus: on 12th February 1851, Edward Hammond Hargraves (1817–1891), along with his guide John Lister and brothers William and James Tom, found five specks of gold in Lewis Ponds Creek in New South Wales, a site they later named Ophir1 – and this event sparked a huge industry of ‘diggers’.

But it turns out that this claim was disputed right from the start, and new evidence and stories have come to light ever since. The one certainty is that 150 years before the internet, people still liked trolling one another, as we’ll see!

Edward Hargraves was born in Gosport, England but went to sea at the age of 14 and soon settled in Australia, where he worked in various jobs including in the tortoiseshell industry, as a steam company agent and as a hotelier. But in July 1849 he felt called by the siren song of the Californian gold rush, which had begun the previous year. He didn’t find much there, but was apparently struck by the similarities in the landscape to the area around Bathurst in New South Wales (NSW). On 5th March 1850 he wrote to his friend Samuel Peek: “I am very forcibly impressed that I have been in a gold region in New South Wales, within 300 miles of Sydney; and unless you knew how to find it you might live for a century in the region and know nothing of its existence.” So Hargraves left San Francisco on 23rd November on a ship called the Emma, and arrived back in Sydney on 7th January 1851, setting off in search of gold just under a month later.

The only extensive account of the actual find is in Hargraves’ fanciful (and believed to have been ghostwritten) 1855 book Australia and its Goldfields. In it he alleges he said to Lister: “This is a memorable day in the history of New South Wales, I shall be a baronet, you will be knighted, and my old horse will be stuffed, put in a glass case, and sent to the British Museum!” (None of this quite happened, luckily for the horse.)

But the first record was this short note written by Hargraves and addressed to the colonial secretary of New South Wales, Sir Edward Deas Thomson: “Wednesday 12th day of February 1851 discovered gold this day – named the diggins ‘Hargraves’, who is the first discoverer in New South Wales of that Metal in the earth in a similar manner as found in California. This is a memorable day.”2 Hargraves went to see Thomson in March, apparently to secure official recognition – and a government handout, which he was later granted (£10,000 from NSW and £5,000 from Victoria).3

Another of Hargraves’ collaborators was Enoch William Rudder (1801–88), who had also been in California; Rudder himself had written to the press in July 1850 about his expectation of there being gold in NSW. It fell to Rudder rather than Hargraves himself to go public about the Ophir finds, and now we begin a heated and rather entertaining series of correspondence from the Sydney Morning Herald.4 I’ll try to let these edited extracts speak for themselves, with just brief interruptions.5

2nd April 1851

GENTLEMEN… A goldfield has been discovered extending over a tract of country of about 300 miles in length… The discovery has been made by a gentleman (an old well known colonist) with whom I had the pleasure to travel many hundred miles when in California, and know him to be a miner of very considerable experience… I trust it will not be long ere… the Government will adopt without delay such measures as shall tend further to develop the riches of this colony and enable the people to reap the golden harvest which now appears to invite attention.

I remain, gentlemen,

Your obedient servant,

E. W. RUDDER.

Sydney

[A few weeks later, an anonymous correspondent weighs in, signing himself – I think we can assume it’s a man – with only this cryptic little symbol: 𐃏]

3rd May

GENTLEMEN,—In this morning’s Herald I find the following statement:- “It is no longer any secret that gold has been found in the earth… by Mr. E. H. Hargraves… While in California, Mr. Hargraves felt persuaded that, from the similarity of the geological formation, there must be gold in several districts of this colony, and when he returned his expectations were realized.”

Here are two asseverations—one as to the date of the first discovery of gold in this colony; the other as to the method by which Mr. Hargrave[s] is asserted to have made that discovery. The object of this letter is to deny to Mr. Hargrave[s] the merit of the first discovery, or that he is the first person who was led to the conclusion that the similarity of formation in California and New South Wales indicated the presence of gold.

I almost wonder how you could have forgotten the many articles connected with this very subject which you have published long ago, even, I believe, before Mr. Hargraves went to California, in which a comparison is instituted between that country and this respecting this very matter of gold-finding…

Now, as to the assertion that it was on the 12th February, 1851, that the said fact was established, if you will turn to your own files you will find that on 28th September, 1847 the geological formation of this colony is investigated, and mention distinctly made of the existence of gold… and some of that gold is still in my possession.

Mr. Hargraves has therefore, merely acted upon suggestions thrown out years ago, and he has, therefore, no claim as a “discoverer.” There are numerous localities in which gold has been found in this colony; but is the Government to pay every individual who picks up a handful of it?

[And now an anonymous defender of Hargraves joins in…]

12th May

GENTLEMEN, In reply to the letter which appeared in your paper of the 5th ultimo headed “the gold discovery,” I have to remark it appears to me to show about as much wisdom as that established by those jealous of that great discoverer Columbus, who, though they could not doubt the truth of his discoveries, found it impossible to make an egg stand on one end. No sooner however was the thing accomplished, than they had the mortification to find it was ridiculously simple. Mr. Hargraves never doubted that others had discovered gold, but could they profit by their discoveries? No, not one of them. Who has done this? Who was the first to show the hidden riches of this vast country? Mr Hargraves… I question if the writer ever discovered anything… Like the bloated frog in the fable who envied the noble ox, the writer of the letter in question has only displayed the fact that his attempts at detraction and his desire to have it inferred he had in some way been injured by Mr. Hargraves’ announcement, must burst, and in so doing reduce him to that mere nothingness which has induced him to act with so much ill taste as to attempt wantonly to detract from the meritorious act of a fellow-colonist…

I am, Gentlemen,

Your obedient servant,

FAIR PLAY.

P.S. … I can assure him I have handled some of the gold of Ophir, and seen a specimen of platina found with it—nay more, I am about to dig for it.

[But 𐃏 fights back!]

13th May

GENTLEMEN, I have but little to say to the extremely vulgar letter of your correspondent “Fair Play,” who, like many who assume that title, seems to be an adept in foul insinuations. If, as he admits, others discovered gold in this country before Mr. Hargraves, why should he object to let those discoverers claim such merit as he assumes himself, if there be any merit at all in the matter? … Mr. Hargraves was not the first person who had arrived at this conclusion, and that instead of 1851, the date of the discovery that gold does exist, in this country, was many years before. In short, it was in 1840.

Whatever may be the value of Mr. Hargraves’ alleged “find,” is to me perfectly indifferent. I neither envy his luck nor covet his gains. And if there is the abundance pretended, I may honestly confess, that I am sorry for it, because though a few persons may succeed in scraping out of the earth a bag of gold dust, the mischief which would accrue to the colonists by a mania for gold hunting is so fearful to contemplate (with the example of California before our eyes), that no person well disposed to the quiet progress of our social and moral state, can desire the dreams of a Midas or an Aladdin to be realised…

I think it possible “Fair Play” may have overlooked a very important point. At present, the public know nothing about the amount or extent of the gold field, and therefore nothing of the value of Mr. Hargrave’s alleged “find.” The Columbus egg of that gentleman may, perhaps, be discovered an “addled one,” i.e., though there is gold, it may not be as abundant as it is in California.

[Two weeks later, Hargraves himself wrote to the newspaper, warning people against the very gold rush he had effectively started. He also alludes to prior claims by the Rev. William Branwhite Clarke (1798–78), who had apparently found gold in 1841 and taken it to the governor of NSW, George Gipps, who urged him to keep the whole thing quiet: “Put it away, Mr Clarke, or we shall all have our throats cut.”]

27th May

GENTLEMEN,—Having passed on my road from Bathurst from 800 to 1000 people who are off to the diggings, to say nothing of the inability of a great portion of these people to endure the necessary labour to obtain gold, not ten per cent of the whole have any tools to work with, or a single pound to support themselves during their journey to the mines. Gold digging is very hard work; the season of the year is against carrying on operations in mining; a few hours’ rain would put an entire stop to digging, as the creek rises many feet in a single hour…

I regret exceedingly to hear many poor people have left their employment for the purpose of seeking their fortune in the precarious occupation of gold digging. I venture to predict a very small percentage will do good, and a very great amount of human misery must be the result of this reckless digging mania…

I may take this opportunity of saying, with reference to remarks said to have emanated from the Rev. W. B. Clarke, as to prior claims to the discovery of gold, that I never had the slightest idea of any such discovery, if it ever took place…

Time will prove the correctness of the statements of

Yours, obediently,

EDWARD HAMMOND HARGRAVES

Steamer Comet

[That letter was published on 28th May, and the next day W. B. Clarke himself contributed a 2,500 screed to the newspaper about the history of his thoughts on gold in the area from his perspective as a geologist. It’s too dry to include here, but he does comment: “I have no interests at heart but those which I believe to belong to all members of a civilized community,—the common good, which I sought when I withheld more pointed and particular statements than those previously published…” But Hargraves couldn’t resist his own comeback…]

30th May

In yesterday’s Herald appears a statement signed W. B. Clarke, to the effect that Mr. Clarke had long declared that there was gold in this country, but that nobody believed him, and that I was guided to the localities in which I discovered the gold by his published statement. Of the first part of his statement I know nothing; but I most emphatically declare the last statement to be untrue. It may possibly betray ignorance on my part to say so, but to the best of my belief I never even heard of the Rev. W. B. Clarke, of St. Leonard’s parsonage, until within the last few weeks…

I have no desire to acquire notoriety, neither do I take to myself much credit for the discovery; it was the result of observation and reflection, and some little perseverance…

I mentioned my belief of the existence of gold in this colony to several of my most esteemed and sincere friends upon my return… From the best and kindest motives they endeavoured to dissuade me from the enterprise, … but feeling that I could not rest until I had satisfied my mind by a personal search, I went through hundreds of miles of the solitary wilderness, and having made the discovery,6 disclosed it to the Colonial Government, who may or may not reward me for the unbounded wealth which I have, through an overruling Providence, been the humble instrument of conferring on my fellow-colonists.

EDWARD HAMMOND HARGRAVES

Sydney

[These catty exchanges reminded me greatly of the wonderful Gossage–Vardebedian Papers by Woody Allen.]

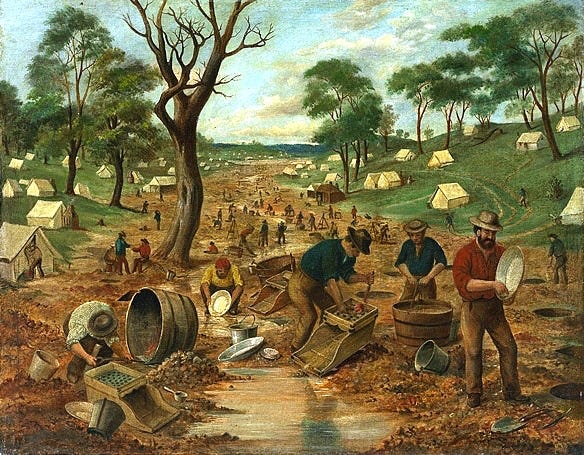

The real truth seems to be that Hargraves was a smart self-publicist and opportunist who perhaps saw that the value wasn’t in the gold itself as much as the awareness of its presence, and in securing official recognition. The well-known 1851 portrait of him below as a benefactor generously waving to the miners fits with his public image, perhaps not fully tallying with the corpulent grandee we see alongside, based on photographs of the time.

The story was far from over. E. W. Rudder’s own 1861 book Incidents Connected with the Discovery of Gold in New South Wales shows that some bitterness had arisen on his side too, suggesting “Mr. Hargraves forgot his friends in the intoxication of success”:

I lay no claim to the Discovery of Gold in Australia. I claim to have laid its foundation, to have been its promulgator, and the first demonstrator of the most simple and efficient method of procuring it… My object is not to lesson any real merit due to Mr. Hargraves as the actual discoverer of “Placer Deposits,” in New South Wales, but… that gentleman has absorbed within himself, not only that to which he was justly entitled, but that which was due to others, never having (so far as I know) in any way acknowledged the assistance he received, but kept their services in the background…

In 1890, a second inquiry was opened, and a parliamentary committee this time declared: “Messrs. Tom and Lister were undoubtedly the first discoverers of gold in Australia in payable quantities.”

But as this list shows, there were many possible claims to the first Australian gold finds, albeit mostly in small quantities. And politics sometimes intervened. In 1848, William Tipple Smith (son of the English geologist William Smith) had also found gold in the Ophir area, i.e. three years before Hargraves. But research published by Smith’s great-great-great-grand-niece Lynette Silver in 1986 revealed that Smith’s correspondence had been misfiled and his claim lost to history (although he found his own success in the iron and steel industry). Smith had taken a nugget of gold to colonial secretary Thomson in 1849, the latter then furtively attempting to buy the land where it was found. Smith was accused of being a liar – so perhaps that paperwork had been ‘lost’ on purpose. Smith’s role was finally acknowledged officially… in 2020.

And where did Smith find it? At a place called Yorkey’s Corner, named after a Yorkshire-born shepherd… who had allegedly found a nugget of gold himself sometime earlier. It doesn’t seem a stretch to say it was known by many people out in the wilds that gold was around – but it took one man to make a craze of it.

Next week: in Part 2 we’ll return to the Australian gold fields a few years later to find out what life as a digger was really like. Thanks for reading – do please tell people about Histories – it all helps motivate me to keep on digging myself!

The name is biblical, from the supposed source of King Solomon’s gold, although Ophir, California was named in 1850 during the gold rush there, which may have influenced Hargraves; some writers have suggested the Toms brothers’ father, William, a parson, coined the name.

This note was rediscovered in 1954, when the Melbourne newspaper The Age reported: “The tattered and torn old document, wrapped round a specimen of the gold, was unearthed from the vaults of an old strongroom at the university by the newly-appointed archivist, Mr D. Macmillan… Still enclosed in the letter when discovered was a sample nugget, beaten flat, and measuring approximately two and three-quarter inches by one inch and weighing just under 2 oz.”

These funds were frozen when John Lister protested, but Hargraves’ claims were upheld in 1853. A detailed account of Hargraves’ life and adventures can be found here.

All available online thanks to the wonderful Trove website run by the National Library of Australia.

The dates are when the letters were written, where given – typically published a day or two later.

This story reinforces a truism which still has currency on the Australian goldfields today: "there is no truth around gold".