'I've got it!', 1822

Cracking a famous code

I do not believe I need to wait any longer to offer to those scholars, and to you, a short but important series of new facts…

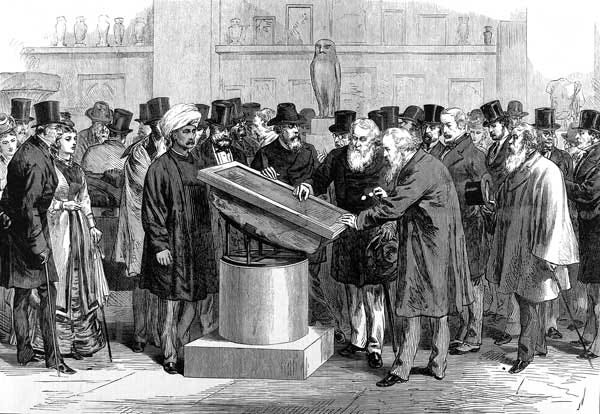

On 27th September 1822 – 200 years ago next week – a 31-year-old French philologist stood up at the Institut de France and addressed the members of the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres. Sitting in the audience by pure chance was the British polymath Thomas Young, both inspiration and rival to the young Frenchman. The Frenchman proceeded to read out a letter he had written five days earlier (and then rushed to have printed in time for this meeting) to Bon-Joseph Dacier, the Académie’s secretary.

The letter elaborated on a discovery the man, whose name was Jean-François Champollion, had made just 13 days beforehand. When he made it, he was so excited that he rushed from his house at 28 Rue Mazarine1 to the Académie and yelled to his elder brother Jacques-Joseph, an archaeologist, “Je tiens mon affaire!” (roughly, “I’ve got it!”),2 upon which he collapsed – so the story goes, anyway. He was bedridden for five days before he bounced back to life to continue his research. His breakthrough, if you haven’t guessed, was unlocking the Egyptian texts on the Rosetta Stone.

The Stone, more than a metre high, was inscribed in 196 BC and famously has the same text in three scripts: hieroglyphics, the later Egyptian Demotic that had evolved from those, and ancient Greek. It came to light when Napoleon’s army was in Egypt in 1799, and its linguistic importance was immediately recognised. Only a year later, however, the same army was defeated by the British – the stone landed in Portsmouth in 1802, was presented to George III and has been in the British Museum ever since.

Over the next two decades, various French and British scholars studied the Stone, including Thomas Young, who made some important observations on the connections between the three texts and indeed discussed it with Champollion in letters – they first met at the 1822 meeting we began with, but their relationship soured over time over the credit for the breakthrough. Young wrote to his friend William Hamilton, a minister at the Court of Naples, on 29th September:3

If he did borrow an English key, the lock was so dreadfully rusty, that no common arm would have had strength enough to turn it… I sincerely wish that his merits may be as highly appreciated by his countrymen and by their government as they ought.

But only weeks later he would note to another friend, MP and poet Hudson Gurney:

How far he will acknowledge every thing which he has either borrowed or might have borrowed from me, I am not quite confident…

Both rivals were dead 10 years later, but this bone of contention if anything grew, and thanks to their various supporters it became a long-running index of Franco–British rivalry. But let’s go back to the excitement of discovery and what Champollion had written in what became known as the ‘Lettre à M. Dacier’. Here’s some of it – the actual breakthrough is perhaps a little dry and technical, but nonetheless this was an important moment in cultural history, and of course the concept the Rosetta Stone embodies has been used as a metaphor ever since.4

Sir,

I appreciate the kindness shown me by the Royal Academy of Inscriptions and Fine-Arts by acknowledging my work on Egyptian hieroglyphics and by permitting me to submit my two papers on the hieratic (or priestly) form of writing, and on the demotic (or popular) form of writing. After such flattering approbation, I dare to hope that I have succeeded in demonstrating that both these two types of inscription are not alphabetical as previously generally accepted, but ideographs, like the hieroglyphics themselves, that is to say, they indicate the ideas not the sounds of the language; and to believe that I have succeeded, after ten years of intensive research, in collecting almost complete data on these two types of inscription, on the origin, nature, form, and number of their symbols and rules of combination, at least those of the symbols which fill the purely logical or grammatical roles, and to have thus cast a firm basis on which to assign a grammar and a dictionary for these inscriptions used on a large number of monuments and whose interpretation will shed so much light on the history of Egypt. In particular, with regard to the demotic inscription, it was enough to recognize it on the precious Rosetta Stone; I am at first beholden to your distinguished colleague Mr. Sylvestre de Sacy, and to the enthusiasm of Mr. Akerblad and Dr. Young, whose first conclusions were drawn from this monument, and it is from this very inscription that I have deduced the series of demotic symbols, which, taking a syllabic-alphabetical interpretation of the ideographic inscriptions, demonstrated the proper names of non-Egyptian individuals. Also, the name of Ptolemy was found on this inscription (the Rosetta Stone) and on a papyrus recently brought from Egypt.

It remains for me to complete my work on the three types of Egyptian inscription, and to prepare my paper on basic hieroglyphics. I hope that my new efforts will also get a favorable response from your esteemed organization, whose kindness spurs me on.

But in this actual state of Egyptian studies, where artifacts are coming from all sides and are being collected by sovereigns and amateurs alike, and scholars from around the world hasten to report their voluminous research and strain to penetrate the inner secrets of these monumental inscriptions which might serve to explain all the others, I do not believe I need to wait any longer to offer to those scholars, and to you, a short but important series of new facts, which will naturally appear in my paper on hieroglyphic inscriptions, and which will undoubtedly save them the trouble that I have taken to establish it, and to avoid serious errors on the diverse ages and history of the arts and general administration in Egypt: for it is the series of hieroglyphs, which making exception for the general nature of symbols in this inscription, were endowed with the ability of expressing the sounds of the words, and served to inscribe on the public monuments of Egypt the names and sobriquets of Greek or Roman rulers who successively governed there. Many certainties of the history of this celebrated country must arise from this new result of my research, to which I was quite naturally drawn.

A comparison of the demotic text on the Rosetta Stone using the Greek text which accompanies it led me to recognize that the Egyptians used a certain number of demotic characters to which they attributed the ability of expressing sounds in order to introduce into their inscriptions proper names as well as words foreign to the Egyptian tongue. One can easily understand the absolute necessity for the use of such a system in ideographic writing. The Chinese, who use an ideographic script, also use a similar method, and created it for the same reason.

[Champollion goes on to detail how he identified the name of Cleopatra in the Rosetta texts. He concludes…]

Finally, I wish here only to present a subject resulting from my phonetic hieroglyphic alphabet, which should result in further developments. The illustrious Academy has already given to Europe much in regard to the old world, and my current presentation will further substantiate the history and civilization of the ancient Egyptians. We can finally read the ancient monuments and follow the ancient Egytian dynasties by comparing the Greek, Roman, and Pharaohic names found in the cartouches. I hope my submission will find favor with the French public, and I once again thank you for accepting my publication.

In later decades the same street was home to the ‘father of anarchism’ Pierre-Joseph Proudhon and the painter Édouard Manet.

Some versions say he cried “Je tiens l’affaire!”

The text here is from an English translation in 2015 by Rhys Bryant based on an annotated and illustrated version of Champollion’s text that was published a month after he had delivered the original version.