From our Special Correspondent, 1860

'Bravo Bravissimo'… but a sad story too.

Certainly life began well for Thomas Bowlby. It would not end that way.

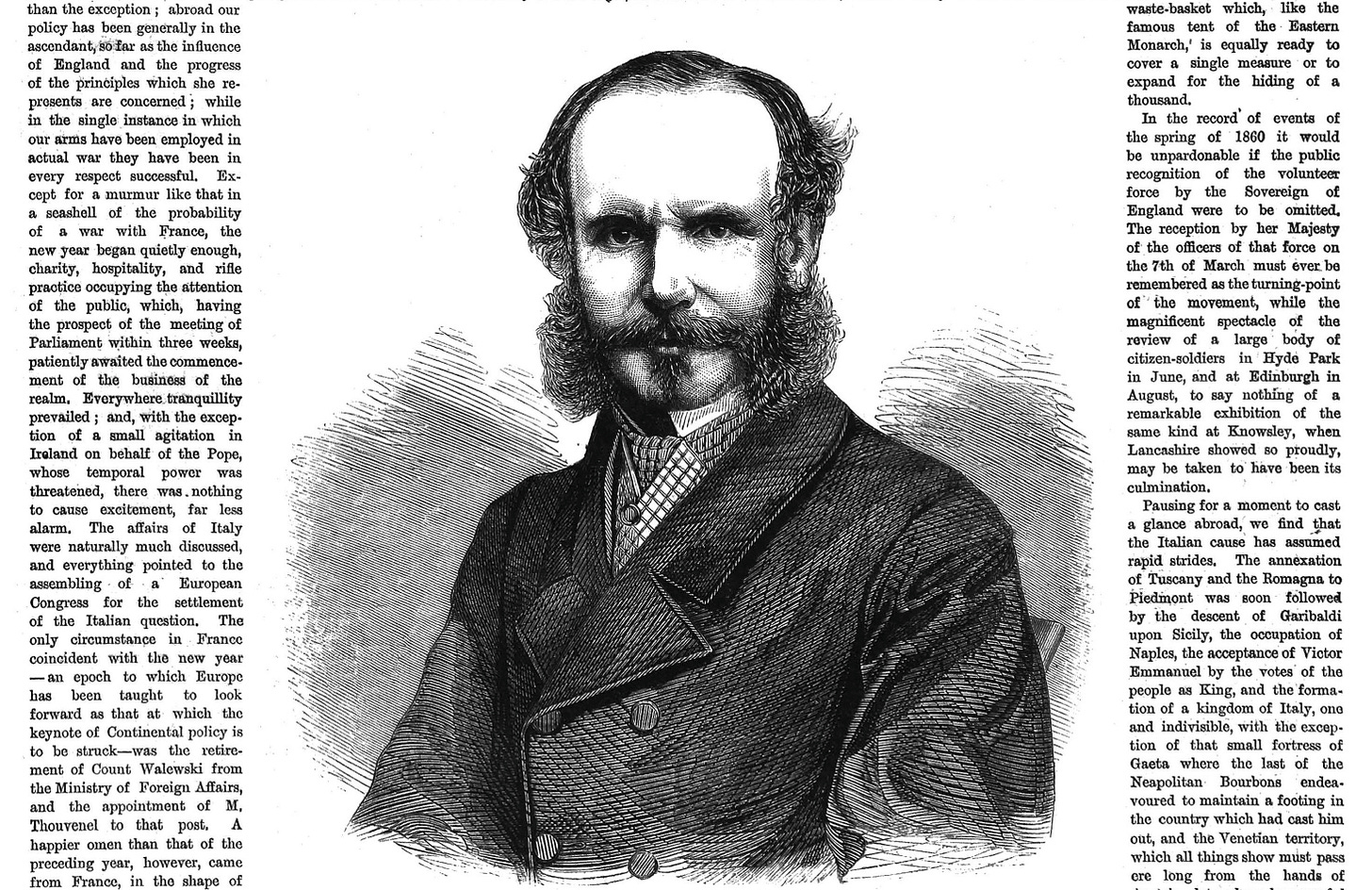

He was born in 1818, in Gibraltar, the son of a British army captain and a wealthy general’s daughter, Wilhelmina Balfour. The family relocated to Sunderland in north-east England, where Captain Bowlby retired from the army and invested in the timber trade as well as shipping and railway ventures. Young Thomas was educated locally, then trained as a solicitor under his cousin Russell.

Having served his apprenticeship, in 1846 Thomas moved to London and worked for a City law firm. In 1848, he married Frances Mein, daughter of an army surgeon,1 and they would go on to have seven children (five surviving infancy). But as time went on, his heart wasn’t quite in a career in the law. He’d made friends in literary circles, and was attracted to journalism.

We don’t know how he got the job, but in 1848 he was appointed as a special correspondent for The Times in Berlin, reporting on affairs such as the Hungarian Revolution. But his financial affairs became messy after some misjudged railway investments and for a few years he fled abroad – four of his children were born in Belgium. Between 1856 and 1858, he was also involved with the development of a railway in Turkey.

And then came 1860 – the best year for Thomas’s career, but also the worst.

In April 1860, Thomas was given his most important commission yet by John Thadeus Delane, editor of The Times since 1841 – to join a joint British and French expedition to China, led by the Earl of Elgin and Baron Gros, as part of the efforts to open up the opium trade.

Thomas Bowlby’s diary2 records his journey in detail, leaving London by train on 26th April and arriving in Folkestone that morning and Paris at nightfall. Thence to Lyons, where he met Lord Elgin and his entourage, and on 30th April they sailed on the SS Valetta for Malta and Alexandria. (At this point his diary is very terse – in Egypt on 4th May he notes, “At 9pm went to the Pyramids and slept at their base.”) Next, from Cairo to Suez on a new railway line, and then on to the steamship SS Malabar, sailing from Aden to Galle in Sri Lanka (then Ceylon). It was here that disaster struck, although it would also make Thomas’s name. Again Thomas’s diary (on 22nd May) is terse: “Wrecked in the Malabar.”

His journalistic instincts kicked in. He wrote in his diary:

The first thing I did after landing was to proceed to the telegraph office in order to send the news to England. I found the wires broken between Galle and Colombo, so I forwarded my message express, by runner…

We’ll come back to that report he filed. He notes how after the wreck he was “soaked to the skin, shirtless and trouserless”. His fellow passengers requisitioned all the local tailors to make them new clothes in haste (“the prices demanded were fabulous and those eventually paid frightfully exorbitant”). And here we have the first of two odd little premonitions relating to this story:

My luggage was insured for £200, about half my loss. I was induced to insure for this amount by Mr. Allen, one of the P. and O. managing directors. At an interview the day before I left London he asked me if I was insured. “No, for if the ship goes down I shall disappear with my baggage.”

“That is not our experience, for we save the passengers when we lose the ship.”

And indeed they did: no lives were lost. A few days later, a thanksgiving service was held at the English church in Galle, and on 28th May Thomas records how “the divers have set to work” at the wreck. One got into the baggage room and “he secured three bags of opium, worth £120 a bag [about £14,000 ($17,500) today], and one or two boxes of bullion”.3 And finally, after an inquiry into the Malabar incident, the party set sail for Hong Kong on 5th June, arriving on the 21st.

Now, if you’ve been following this little series about Britain and China during the Second Opium War, you might well have guessed that Thomas Bowlby was “the Times correspondent” described by Admiral Corbett and travelling with Henry Loch, Lord Elgin’s secretary, and the diplomat/translator Harry Parkes. And like them, he was captured in a Chinese ambush in September.

Thomas Bowlby filed multiple reports for The Times during this Chinese expedition, and after the success of his account of the wreck of the Malabar, he had the nation’s ear.4 In his dispatches, he described the military events from a British perspective, but also admired China’s buildings and gardens and showed sympathy for Chinese civilians killed in the conflict. His last report was filed at 6 am on 11th September, 45 miles out of Peking, lyrically describing the landscape and the weather, and noting “a flag of truce has just come in”. His last diary entry is dated 16th September, describing a “long talk with Lord Elgin”, who was keen on military advance.

A few days later, Thomas William Bowlby was dead.5

We don’t really know exactly what happened to him. He was captured along with Loch and Parkes, but appears to have been one of a few men who suffered too greatly from their captivity to make it out like those two did. One man, a Captain Anderson, had been hog-tied, with water poured on the rope to tighten the binding, and died as a consequence, the full details too horrible to relate here (a Sikh captive who was released did note “Mr Bowlby’s hands were not so much swollen”). Henry Loch reports that the bodies were only retrieved on 16th October:

Quicklime had destroyed their features but we recognised them by their clothes, and Bowlby, poor fellow, we also knew from the peculiar formation of his head and brow and by a peculiarity in one of his feet.

A day after that, Bowlby and others were buried in the Russian Ecclesiastical Mission cemetery outside one of Peking’s gates. The site is now lost under a golf course, though memorials to Thomas were created in Paddington Old Cemetery in London, where his wife was buried in 1891, and in Bishopwearmouth, Sunderland.6 In a letter to Delane on 25th October, Lord Elgin said he considered the loss of Bowlby “to be a great calamity”.

On Christmas Day, 1860, The Times’s lead article reported on the “tidings of peace” in China, but there was a darker note. It said the graves of Bowlby and his fellows “may serve to record the crime of which the blackened ruins of the Summer Palace of the Emperor will long record the punishment”.

And thereby hangs a tale: that palace (Yuanmingyuan, famed for its architecture and gardens) had been captured on 9th October, and so incensed by the loss of these men was Lord Elgin that on the 18th, the day after Bowlby’s funeral, he ordered its destruction. Three and a half thousand troops set it on fire (having already looted its treasures), unaware that around 300 servants and eunuchs were hiding in the buildings. Even one of the looters, a young man who would later find fame as General Gordon of Khartoum, observed “it was wretchedly demoralising work for an army”. The British and French forces involved left a plaque at the site reading ‘This is the reward for perfidy and cruelty’.

Today that site is remembered by the Singing Crane Garden and a museum of art and archaeology created in collaboration between China and the West in the 1990s. But old wounds run deep.7

Before we close, I’d like to go rewind the time machine clock by five months and honour Thomas Bowlby with just a very short extract from his account of the wreck of the Malabar. The full piece runs to well over 6,000 words – Delane of The Times wrote to Bowlby to say it was a “most perfectly told story… read everywhere with… breathless interest”. A friend declared on reading it, “Bravo Bravissimo my dear Bowlby!”

About half-past 2 o’clock the Malabar’s commander, Captain Grainger, goes to his cabin for a change of clothes. He is hardly there when, suddenly and without a moment’s notice, comes a terrific squall from the north-east. It sweeps across the bay, and strikes the Malabar on her port side, causing her to heel completely over. The mooring hawser snaps, and she swings round head to wind, completely reversing her former position. Then comes a shock which shakes the vessel from seem to stern; a second, which brings the saloon skylight crashing into the cabin. Again, again, again, and lamp after lamp is shivered to pieces. We are on the reef, and the rocks are smashing in our plates one after another. Captain Grainger is on the bridge—the engineer at his post, but the steam is not up, and the ship crashes and crunches with every swel. The pumps are sounded, and give three feet and a half water in the after compartment. Five minutes later and five feet are announced. Our position is most critical; not a boat alongside, not one of the ship’s boats ready for launching. Before us is the bay with its roaring swell; behind, at 400 yards distance, the fort, with the sea dashing over the rocks which jut into the water, and breaking in tremendous spray right against the parapet wall. The wind still keeps from the north; if it does not shift, but a few minutes and all will be over. Hold on by the anchor, let it drag but six feet and the engine compartment will be smashed to pieces. Let those heavy engines descend with all their weight on those pointed rocks, and our vessel must split in two. A double danger then awaits us. We shall be blown into the air by collapse of the boilers, or down we shall go among the sharks and the breakers. The anchor holds. The squall abates, the wind goes back to the south. She swings clear of the reef. But now commences a new peril. The after compartments are filling fast, and she is visibly settling by the stern. The water rushes into the tunnel and indicates seven feet in the hold. Unless steam be got up, down she must go, stern first, in a very few minutes. A panic seizes some—happily but a few—of the passengers. A rush is made to the boats…

One final note. I mentioned two premonitions. Here’s what Elgin also wrote in his letter to Delane, looking back to the events of September:

Mr. Bowlby said to me, “Would you have any objection, my Lord, to my going with Parkes tomorrow?” I was somewhat taken aback by the proposal, but I answered, “I have no objection; but remember, if you are put into a cage, I shall have to come and let you out.”

“Oh,” said he, “there is no danger of that.”

And confusingly the half-sister of Thomas’s father’s new wife after Wilhelmina had died in 1834 when he was only 16. For more on Thomas’s family background, see here.

Bowlby’s diary was rediscovered in 2015, although the details of his China voyage were published in 1906 in my main source for this article: An Account of the Last Mission and Death of Thomas William Bowlby, compiled by one of his sons.

Bowlby’s Times report reveals that the ship was carrying more than 1000 boxes of bullion and 725 chests of opium!

In The Times on 18th June 2004 (‘A Times man in war torn China’), his descendant Ronald Bowlby noted, “The detailed descriptions of the Chinese countryside and people, as well as of the military forces, make fascinating reading.”

Some accounts say he died on 22nd September, although there are discrepancies in the first-hand reports.