Encounters on the road to Candandaigua, 1794

Part 1. What did the doctor have to boast about?

(Hello, this is Histories, a free weekly email exploring first-hand accounts from the corners of worldwide history… Do please share this with fellow history fans and subscribe!)

The warriors had each a tomahawk in his hand, they would begin to beat the drum very slowly and the singers and rattlers would keep time by it… and when they halted one of the company attending would come forward and strike the war post…

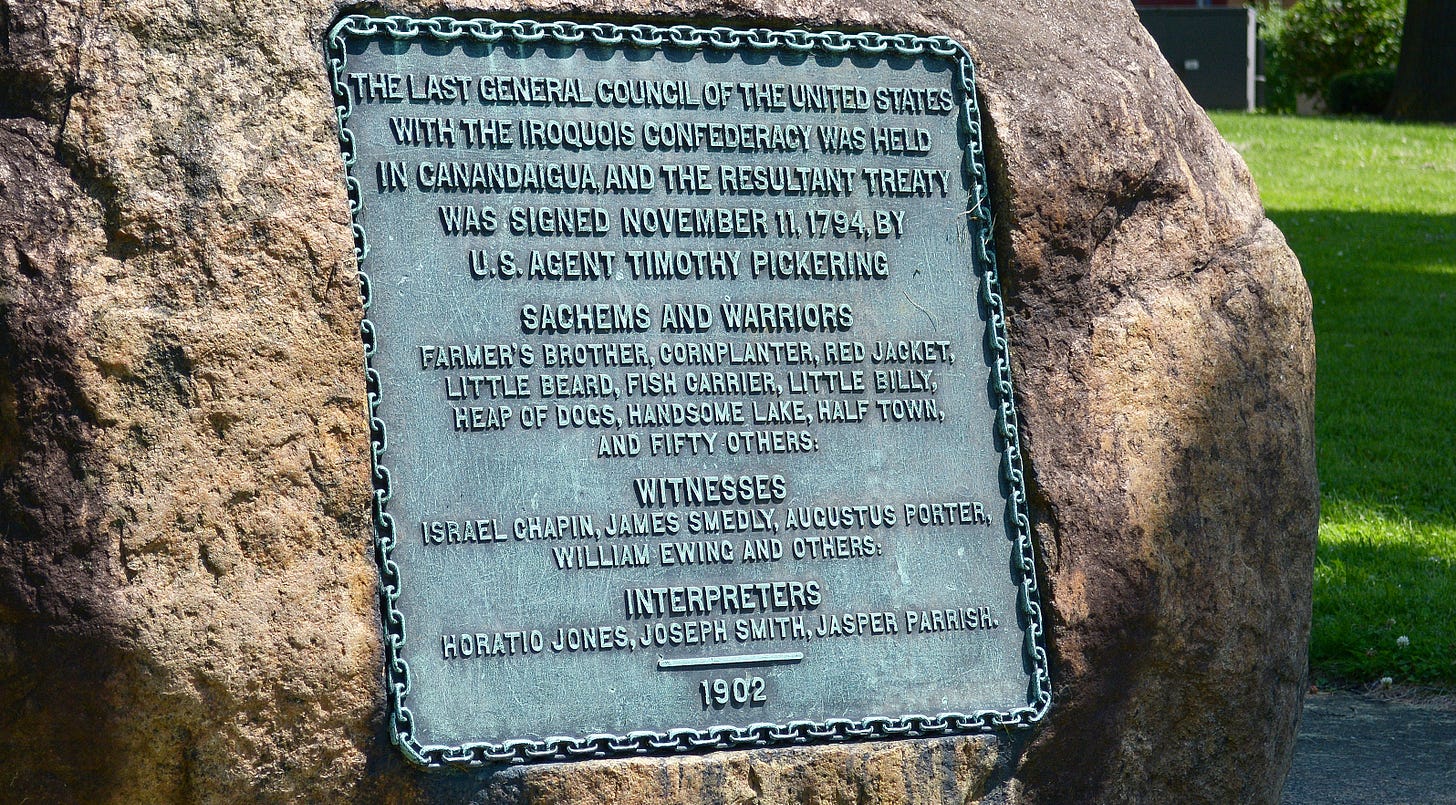

On November 11, 1794, 59 Iroquois chiefs met with Colonel Timothy Pickering, official representative of George Washington, at a small settlement in western New York state, and together they signed the Treaty of Canandaigua. This was an attempt at securing peace amid tensions between the fledgling independent United States and the American Indians of this region, tensions exacerbated by complex feelings on both sides towards its previous occupants, the British. Some of the promises made by the US government to the Six Nations of the Iroquois were kept; and some weren’t. So it goes.

But there was a third group present at the signing: a small party of Quaker observers, who had been invited to attend by both sides. “We meddle not with the affairs of government,” the Quakers of Philadelphia had said in an address to the Six Nations back in September 1794, “but we desire to do all we can to preserve and promote peace and good-will among all men.”

The four observers who set out on the road from Philadelphia, though Pennsylvania and on to western New York, were:

William Savery (1750–1804), whose name has clung to history because he was a notable influence on the British social reformers Elizabeth Fry and William Wilberforce.

James Emlen (1760–1798), another elder, who after the treaty became a member of the Committee on Indian Affairs, a version of which is still running today. Sadly he died of yellow fever in his thirties – the same disease which killed his wife and left him to bring up their six children.

David Bacon (1729–1809), a Quaker elder and son of a Philadelphia hatter. Like Emlen, he had six children.

John Parrish (1730–1807), born in Baltimore and a renowned opponent of slavery best known for his 1806 pamphlet ‘Remarks on the Slavery of the Black People’.

All four of these observers were earnest supporters of the abolition of slavery and the rights of the indigenous peoples, and kept journals of their involvement with various treaties and peacekeeping. The first three of them all wrote about their journey to Canandaigua. They show great feeling for the Native Americans, and had some interesting encounters along the way.

Savery’s journal was later edited and published, and focuses on the politics, but with a sympathetic note for the poverty-stricken people they encountered on their journey. On September 21st, for example, he describes a night spent with a poor family of settlers at a place called the Block House:

I could but admire how very few, even of what are called the necessaries of life, supported this family; the children , however, have a far more healthy appearance than is common in luxurious and populous cities ; and having near thirty miles to send for salt, sugar, flour, and other necessaries, a girl about fourteen, and a boy about thirteen years of age, generally perform the journey alone, sometimes lying all night in the woods. We had to lie on the floor, with the house open on all sides; yet were content, though we slept but little.

Bacon’s account (lightly edited here) is poorly written and sketchy, mainly preoccupied by the bad roads and wet weather, but he mentions this lodging too:

Before when we got there J. inquired of the woman of the house what she had to eat. She informed us they had no bread nor meat milk nor butter nor sugar but she had some meal & elk’s fat of which she made some cakes, which with some weak coffee we maid a good supper. Tied our horses to the trough, for there was no stable nor hay. Laid down on the floor.

And here’s Emlen’s version, too:

We reached the Block House near dark; here, on being told that they had neither bread nor meat for ourselves [nor] hay or pasture for our horses, some gloomy sensations might have ensued, had they not been counteracted by the uncommon hilarity of our host, who being an Alsatian partakes of all the vivacity of the French nation: however, by the addition of some elk’s fat to flour our landlady had made us some tolerable cakes; for which, and a dish of coffee without cream or sugar, some oats for our horses & a bed on the floor we had to pay 32/.

Meanwhile Savery seemed to be almost envious of the Indians’ lifestyle. On November 1st, only days before the treaty was signed, he wrote:

The ease and cheerfulness of every countenance, and the delightfulness of the afternoon, which these inhabitants of the woods seemed to enjoy, with a relish far superior to those who are pent up in crowded and populous cities, are combined to make this the most pleasant visit I have paid the Indians, and induced me to believe, that before they became acquainted with white people and were infected with their vices, they must have been as happy as any in the world.

And two days beforehand Bacon was also impressed:

We went to see the Indian camp. It is admirable to see how soon those people can build a town so as for them to live in comfortably in their way I believe in one day and a half or 2 days they had near 300 of their houses built, & we found the women at work at several branches of business, some making moccasins, others belts & shifts & baskets & cooking venison plenty, the men mostly gone to Council…

And Emlen echoes Savery’s perhaps idealised impression: “We are very apt to condemn any natural practices which differ from our own, but it requires a greater conquest over prejudices & more penetration than I am master of clearly to decide that we are the happier people.”

In general, Emlen’s account offers the richest impressions of the landscape and the variety of people they encounter. He marvels at the impressive rhetoric of the Seneca chief known as Farmer’s Brother: “Farmer’s Brother is a man of large stature, the dignity & majesty of his appearance, his sonorous voice & expanded arm, with the forcible manner of his utterance delivered in a language to us unintelligible reminded me of the ancient Orators of Greece & Rome.” And he boggles at an Indian named Sharp Shins who was “accounted the swiftest runner in the Six Nations; many of his feats were related, amongst others that he had gone on foot about 90 miles to Niagara in a little more time than from sunrise to sunset.” That would look pretty good on Strava.

But my favo(u)rite1 episode is when Emlen provides a rare account of an Indian ‘brag dance’. In fact, these had been described by another travel(l)er in the same year, 1794, the surveyor and pioneering viticulturist John Adlum, who witnessed a brag dance at Chief Cornplanter’s village. Adlum wrote in his memoir:

The warriors had each a tomahawk in his hand, they would begin to beat the drum very slowly and the singers and rattlers would keep time by it… and when they halted one of the company attending would come forward and strike the war post by which I was sitting… and the person who struck it would boast of some feat he had done in the wars. I had no doubt but that they sometimes exaggerated— And if the braggart thought he had related a feat, that none present could exceed, he would throw on the ground a small piece of tobacco wrapped in a leaf or other substance, at the same time saying if any of you can beat that (meaning the story) take it up and let us hear what you have to say— It was always taken up and sometimes a more extraordinary story told.

And here is Emlen’s account…2

In passing thro’ the Indian camp some of them were engaged in what they call a Brag dance, at which time any of spectators have a right, after presenting a bottle of rum to make their boast of what great feats they had done in the course of their lives.

This was done in rotation by the bystanders, both Indians & Whites, when each in his turn recounted all the heroic actions of his life, how many battles he had been in, how many scalps he had made, how many prisoners he had taken &c.

Amongst the rest of the spectators there being a sensible doctor of the neighbourhood present, he after delivering his bottle, made his brag, which he did by informing them, “that he had been a man of peace all his days, that his profession was to use his utmost endeavours to save men’s lives, wherein in many instances he hoped that he had been successful, that a child was capable of taking the life of a fellow creature, but that it required a man of judgment & skill to save it.”

This kind of boasting being its nature novel amongst the Indians gained their universal applause.

Something worthwhile to boast of indeed.

But this wasn't the only striking encounter on this journey, so unusually I’m making this a two-parter – and next time we’ll meet one of the most remarkable figures of late 18th century America…

Sorry, I’m a Brit myself, so I’m trying to be democratic with my spelling.

I came across this, and as a result the whole story of this journey, thanks to Liz Peretz, whose new book In Pursuit of a Better Life (which I typeset) tells the story of her forebear Judah Colt (1761–1832), whose own journals recount his life as a settler and wealthy trader west of the Allegheny Mountains.