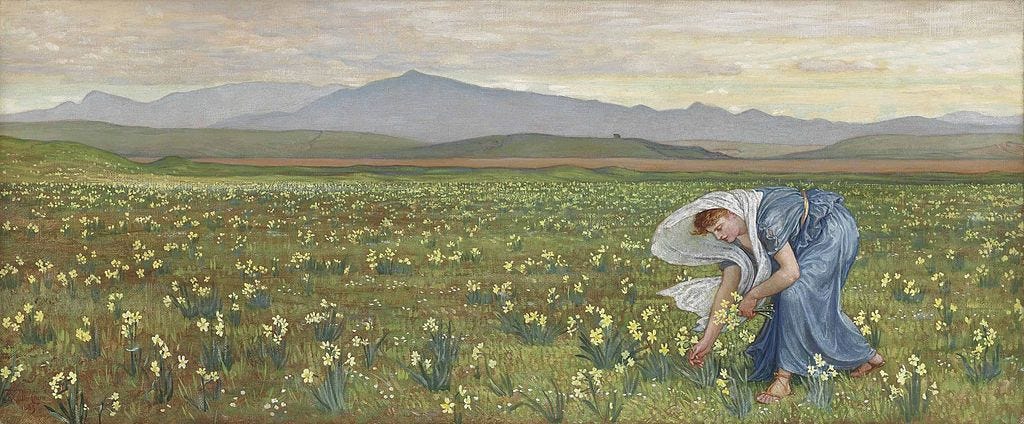

Daffodils, 1802

A sometimes uncredited muse

I never saw daffodils so beautiful… some rested their heads upon these stones as on a pillow for weariness and the rest tossed and reeled and danced and seemed as if they verily laughed with the wind that blew upon them over the lake…

Lists and polls of Britain’s favourite poems almost invariably include ‘I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud’ by William Wordsworth (1770–1850). It was first published in 1807, and Wordsworth himself appended this note: “Town-End, 1804. The two best lines in it are by Mary.” (Town-End refers to his home Dove Cottage in that part of Grasmere, and Mary to his wife – née Hutchinson – whom he married in 1802.)1 Wordsworth’s amanuensis Isabella Fenwick (1783–1856) later added this comment from his 1843 dictations to her:

The daffodils grew, and still grow, on the margin of Ullswater, and probably may be

seen to this day as beautiful in the month of March, nodding their golden heads beside the dancing2 and foaming waves.

But in fact another presence hides behind the poem, and is perhaps the truest muse for it.

Last week I looked into the poet Coleridge’s pioneering account of mountain climbing, and briefly mentioned how Wordsworth appropriated his sister Dorothy’s account of a similar climb, using it uncredited in his 1810 book A Guide through the District of the Lakes (he nicked another section from her, too). Dorothy (1771–1855) is known to have influenced his ground-breaking collaboration with Coleridge, Lyrical Ballads, and her own lyrical journals from their time in Grasmere in particular, rich with descriptions of nature and its effect on the human soul, clearly inspired them.

Perhaps there’s no better example than her account of a walk she took with her brother on 15th April 18023 – 220 years ago to the day as this newsletter goes out – around Glencoyne Bay at Ullswater. It may have taken two years for William to experience “emotion recollected in tranquillity” and write the poem, but the inspiration is clear.

Thursday 15th. It was a threatening misty morning—but mild. We set off after dinner from Eusemere. Mrs Clarkson [Catherine Clarkson, a family friend] went a short way with us but turned back. The wind was furious and we thought we must have returned. We first rested in the large Boat-house, then under a furze Bush opposite Mr Clarkson’s. Saw the plough going in the field. The wind seized our breath the Lake was rough. There was a Boat by itself floating in the middle of the Bay below Water Millock. We rested again in the Water Millock Lane. The hawthorns are black and green, the birches here and there greenish but there is yet more of purple to be seen on the Twigs. We got over into a field to avoid some cows—people working, a few primroses by the roadside, woodsorrel flower, the anemone, scentless violets, strawberries, and that starry yellow flower which Mrs C. calls pile wort [lesser celandine].

When we were in the woods beyond Gowbarrow park we saw a few daffodils close to the water side. We fancied that the lake had floated the seeds ashore and that the little colony had so sprung up. But as we went along there were more and yet more and at last under the boughs of the trees, we saw that there was a long belt of them along the shore, about the breadth of a country turnpike road. I never saw daffodils so beautiful they grew among the mossy stones about and about them, some rested their heads upon these stones as on a pillow for weariness and the rest tossed and reeled and danced and seemed as if they verily laughed with the wind that blew upon them over the lake, they looked so gay ever glancing ever changing. This wind blew directly over the lake to them. There was here and there a little knot and a few stragglers a few yards higher up but they were so few as not to disturb the simplicity and unity and life of that one busy highway.

We rested again and again. The Bays were stormy, and we heard the waves at different distances and in the middle of the water like the sea. Rain came on—we were wet when we reached Luffs but we called in. Luckily all was chearless and gloomy so we faced the storm—we must have been wet if we had waited—put on dry clothes at Dobson’s. I was very kindly treated by a young woman, the Landlady looked sour but it is her way. She gave us a goodish supper. Excellent ham and potatoes. We paid 7/ when we came away. William was sitting by a bright fire when I came downstairs. He soon made his way to the Library piled up in a corner of the window. He brought out a volume of Enfield’s Speaker, another miscellany, and an odd volume of Congreve’s plays. We had a glass of warm rum and water. We enjoyed ourselves and wished for Mary. It rained and blew when we went to bed. N.B. Deer in Gowbarrow park like skeletons.

The “two best lines” are said to have been these:

They flash upon that inward eye

Which is the bliss of solitude

The poem was revised in 1815, and Wordsworth actually changed the ‘dancing daffodils’ of line four with the ‘golden daffodils’ we tend to recall today.