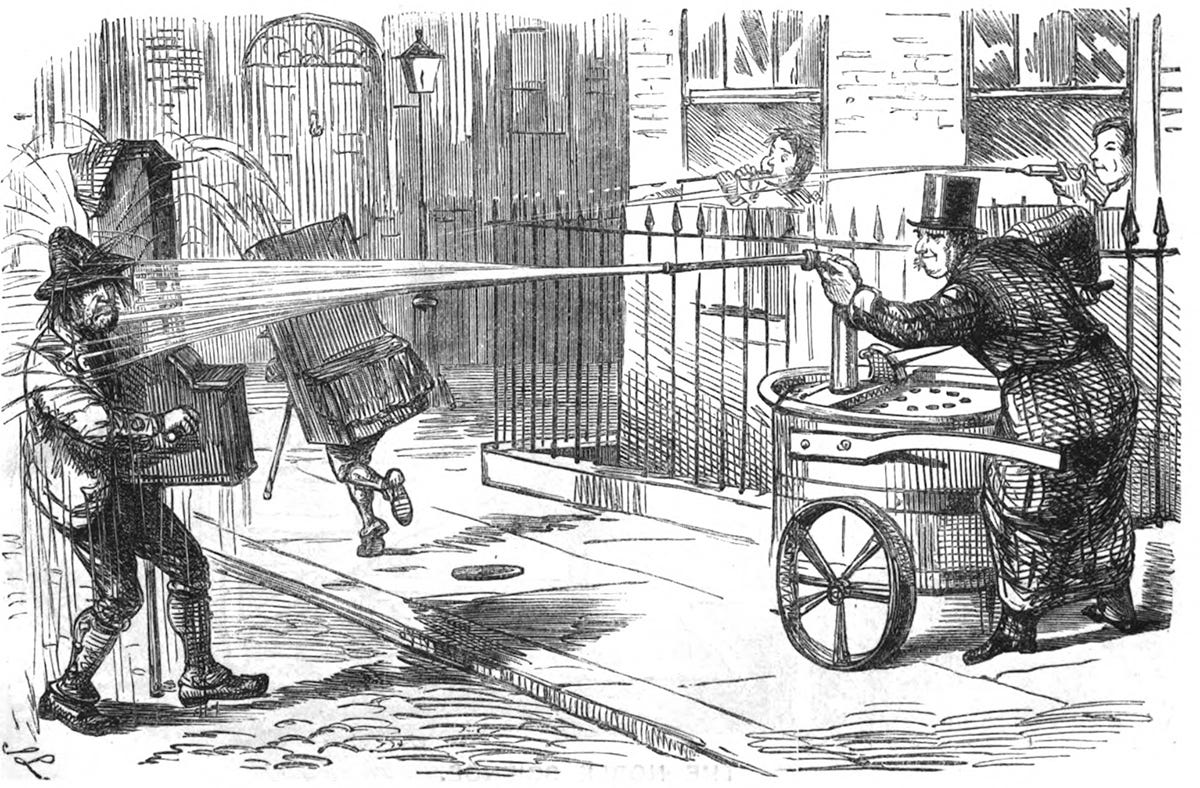

Continual interruptions, 1864

The organ-grinder, not the monkey

It robs the industrious man of his time; it annoys the musical man by its intolerable badness; it irritates the invalid… and it destroys the time and the energies of all the intellectual classes of society…

Last week I looked at the first iteration of Charles Babbage’s Difference Engine, and how he struggled with both financing his projects and bringing them to satisfactory completion (another possible reason for which we will come to). He was a remarkable intellect nonetheless, and either wrote about or conceived inventions across many fields. His enquiring mind was also closely bound, it seems, to a cantankerous personality.

As a child, Babbage (1791–1871) showed early prowess in both mathematics and classics, despite poor health, and in 1810 was sent to the University of Cambridge, where he excelled – although even then he was accused of blasphemy over his contention that God was not a spiritual force but rather a material agency of some kind. The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography describes him as a “spirited undergraduate” who would play whist all night, admired Napoleon and railed against the religious strictures in universities in that era (although he remained a firm Christian throughout his life).

After his studies, Babbage helped to found the Royal Astronomical Society, returned to academia as a professor at Cambridge (in a post held by Stephen Hawking 150 years later) and even dabbled with politics. He also initiated a spat with the Royal Society after his 1830 work Reflections on the Decline of Science, which grumbled about the society as well as lack of proper funding.1 An article in the 13th August 1831 edition of Mechanics’ Magazine took him and other critics to task:

… let us take Mr. Babbage, the gentleman who has put himself at the head of the malcontents: does he not delight to indite after his name, even in the title-page of his doleful Jeremiad [i.e. the book mentioned above], “Lucasian Professor of Mathematics in the University of Cambridge”? True, this is not a government office, but it is one of a public nature, and, we suppose, not without its emoluments, of some sort or other. Then, again, is he, or is he not, the same Charles Babbage, Esq., to whom a sum of some twelve thousand pounds sterling has been voted by the House of Commons, to enable him to bring to perfection a certain calculating machine, which is to do Wonders when it is completed! If this be not giving some encouragement to science, what is? At any rate we think Mr. Babbage should be the last man to complain.

But later in life Babbage developed a very particular obsession with what he called “street nuisances”, driven in part by his own sensitivity to noise, which has led modern writers to suggest he had misophonia or was on the autism spectrum, and a post-mortem examination of his head (the report was only rediscovered in 1983) found a problem that might have affected his hearing. So we should bear that in mind when we read his vehement complaints that I present below – although he was clearly enjoying his theme to some degree. He seems to epitomise the archetype of the ornery grouch who seems to make things worse for himself by getting involved – but the treatment he received was also very cruel.

Here, then, is an extract of the ‘Street Nuisances’ chapter of his 1864 autobiography,2 based on an earlier pamphlet he had written:

During the last ten years, the amount of street music has so greatly increased that it has now become a positive nuisance to a very considerable portion of the inhabitants of London. It robs the industrious man of his time; it annoys the musical man by its intolerable badness; it irritates the invalid; deprives the patient, who at great inconvenience has visited London for the best medical advice, of that repose which, under such circumstances, is essential for his recovery, and it destroys the time and the energies of all the intellectual classes of society by its continual interruptions of their pursuits.

[Babbage then lists what he calls different “Instruments of torture permitted by the Government to be in daily and nightly use in the streets of London”, from halfpenny whistles to hurdy-gurdies, as well as the types of people who are “Encouragers of Street Music”, including tavern-keepers, children and “visitors from the country”.]

I have very frequently been disturbed by such music after eleven and even after twelve o’clock at night. Upon one occasion a brass band played, with but few and short intermissions, for five hours.

The habit of frequenting public-houses, and the amount of intoxication, is much augmented by these means. It therefore finds support from the whole body of licensed victuallers, and from all those who are interested, as the proprietors of public-houses.

The great encouragers of street music belong chiefly to the lower classes of society. Of these, the frequenters of public-houses and beer-shops patronize the worst and the most noisy kinds of music. The proprietors of such establishments find it a very successful means of attracting customers. Music is kept up for a longer time, and at later hours, before the public-house, than under any other circumstances. It not unfrequently gives rise to a dance by little ragged urchins, and sometimes by half-intoxicated men, who occasionally accompany the noise with their own discordant voices…

[Of the musical performers, he writes…]

The most numerous of these classes, the organ-grinders, are natives of Italy, chiefly from the mountainous district, whose language is a rude patois, and who are entirely unacquainted with any other. It is said that there are above a thousand of these foreigners usually in London employed in tormenting the natives… One of these, a most persevering intruder with his organ, gave me a false address. Having ascertained the real address, he was sought for by the police for above a fortnight, but not discovered…

It is difficult to estimate the misery inflicted upon thousands of persons, and the absolute pecuniary penalty imposed upon multitudes of intellectual workers by the loss of their time, destroyed by organ-grinders and other similar nuisances…

Even policemen have frequently told me that organs are a great nuisance to them personally. A large number of the police are constantly on night duty, and of course these can only get their sleep during the day. On such occasions their rest is constantly broken by the nuisance of street music.

Various accidents occur as the consequence of street music. It occasionally happens that horses are frightened, and perhaps their riders thrown; that carriages are run away with, and their occupiers dreadfully alarmed and possibly even bruised…

[Babbage details a newspaper report of an accident of this kind where six children were injured. Later he also complains about another common street scene and its dangers: “A similar cycle occurs with children’s hoops: they are trundled about until they get under horses’ legs.” He also moans about his changing neighbourhood in London in terms we can still imagine people using today…]

Many years before I had purchased a house in a very quiet locality, with an extensive plot of ground, on part of which I had erected workshops and offices, in which I might carry on the experiments and make the drawings necessary for the construction of the Analytical Engine. Several years ago the quiet street in which I resided was invaded by a hackney-coach stand. I, in common with most of the inhabitants, remonstrated and protested against this invasion of our comfort and this destruction of the value of our property. Our remonstrance was ineffectual: the hackney-coach stand was established.

The immediate consequence was obvious. The most respectable tradesmen, with some of whom I had dealt for five-and-twenty years, saw the ruin which was approaching, and, wisely making a first sacrifice, at once left their deteriorated property as soon as they could find for it a purchaser. The neighbourhood became changed: coffee-shops, beer-shops, and lodging-houses filled the adjacent small streets. The character of the new population may be inferred from the taste they exhibit for the noisiest and most discordant music…

Some of my neighbours have derived great pleasure from inviting musicians, of various tastes and countries, to play before my windows, probably with the pacific view of ascertaining whether there are not some kinds of instruments which we might both approve. This has repeatedly failed, even with the accompaniment of the human voice divine, from the lips of little shoeless children, urged on by their ragged parents to join in a chorus rather disrespectful to their philosophic neighbour.

The enthusiasm of the performer, excited by such applause, has occasionally permitted him to dwell too long upon the already forbidden notes, and I have been obliged to find a policeman to ascertain the residence of the offender. In the meantime the crowd of young children, urged on by their parents, and backed at a judicious distance by a set of vagabonds, forms quite a noisy mob, following me as I pass along, and shouting out rather uncomplimentary epithets. When I turn round and survey my illustrious tail, it stops; if I move towards it, it recedes: the elder branches are then quiet—sometimes they even retire, wishing perhaps to avoid my future recognition. The instant I turn, the shouting and the abuse are resumed, and the mob again follow at a respectful distance… In one case there were certainly above a hundred persons, consisting of men, women, and boys, with multitudes of young children, who followed me through the streets before I could find a policeman.

[Babbage was also the victim of worse abuse…]

At an early period when I was putting the law in force, as far as I could, for the prevention of this destruction of my time, I received constantly anonymous letters, advising, and even threatening me with all sorts of evils, such as destruction of my property, burning my house, injury to myself. I was very often addressed in the streets with similar threats. On one occasion, when I was returning home from an affair with a mob whom the police had just dispersed, I met, close to my own door, a man, who, addressing me, said, “You deserve to have your house burnt, and yourself in it, and I will do it for you, you old villain.”…

I will not describe the smaller evils of dead cats, and other offensive materials, thrown down my area; of windows from time to time purposely broken, or from occasional blows from stones projected by unseen hands…

[Being Charles Babbage, he also submitted this theme to his own mathematical analysis…]

It has been found, upon undoubted authority, by returns from benefit societies, that in London, about 4.72 persons per cent, are constantly ill. This approximation may be fairly assumed as the nearest yet attained for the population of London. It follows, therefore, that about forty-seven out of every thousand inhabitants are always ill…

In Manchester Street, which faces my own residence, there are fifty-six houses. This, allowing the above average of ill-health, will show that about twenty-six persons are usually ill in that street. Now the annoyance from street music is by no means confined to the performers in the street in which a house is situated. In my own case, there are portions of five other streets in which street music constantly interrupts me in my pursuits. If the portions of these five streets are considered to be only equal in population to that of Manchester Street, it will appear that upwards of fifty people who are ill, are constantly disturbed by the same noises which so frequently interrupt my own pursuits…

Babbage was not alone in his complaints – the Liberal MP and brewing magnate Michael Bass proposed the Street Music (Metropolis) Bill to Parliament. The parliamentary record Hansard reported3 that he spoke on how “Street music had become so intolerable that it was absolutely necessary that some measure should be adopted for its regulation” – and even records the parliamentary laughter when Bass said “Mr. Babbage had told him that one-fourth of his time was consumed by the hindrances occasioned by street bands, and that in the course of a few days he was interrupted 182 times.” The law was approved in July 1864, although the story goes that when the great inventor was on his deathbed, the organ-grinders returned outside his house to torture him.

Elsewhere in his diatribe, Babbage forlornly notes:

In several of these cases my whole day’s work was destroyed, for they frequently occurred at times when I was giving instruction to my workmen relative to some of the most difficult parts of the Analytical Engine.

Could we even say that the organ-grinders of London held back the history of computing – or was it just another excuse by a genius who found it hard to finish things? You’ll have to decide for yourself.

Misophonia or not I think he was a lot of a curmudgeon; why not move a little out of the centre of the metropolis? The world it seems, must bend to Mr Babbage.